1961年末にロサンゼルスの新日米新聞社より出版された1431ページにおよぶ「米國日系人百年史」のあとがきを「編者」として、取材、執筆にもあたった加藤新一がまとめている。

そのなかで加藤は、「戦後は米本土の殆ど全域に及ぶ米國日系人の歴史を、今にして誰かが綴り残さなくては、日本民族が、この北米大陸に苦闘を重ねて築いた貴い『百年』の歴史を湮滅することを恐れた」と、使命感を示している。

また、どのような出版物にするかについては「百年の奮闘報告書」として、日本へ向けて日系人の歴史を残し、かつ将来誰かが綴るであろう英文による「在米日系人史」の資料として次世代に残すということを主眼にしたという。

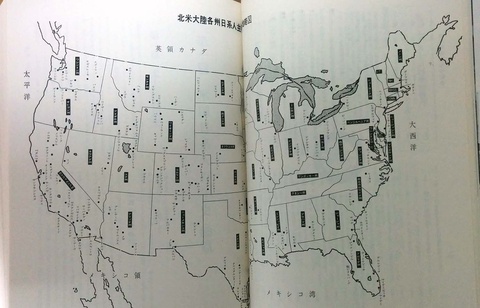

こうした意図のもとに、加藤は1960年の6月以来9ヵ月をかけ4万マイル(約6万4000キロ)におよぶ全米各州への自動車独走の取材旅行に出たと記している。アメリカの東西横断がざっと3500マイルだから11回横断した距離に匹敵する旅である。しかし実際はもっと長かったのかもしれない。

本書の翌年に、この百年史のダイジェスト版のようなかたちで加藤は「アメリカ移民百年史」(時事新書)を著している。

そのあとがきでは「なにかに『ツかれた』というが、全くカリフォルニアから行を起こし、華氏百度前後の酷暑のまっただなか、また零下十度前後の極寒の雪中突破など全米を回ってロサンゼルスに帰るまでの十ヵ月、八万キロ(5万マイル)に及ぶ自動車による独走旅行を強行し、自分ながらよくやり通せた-と『健康』を与えられた天と亡き両親に感謝したこと、再三であった」と振り返っている。

取材にあたったとき加藤はすでに還暦を迎えているが、「40年近い新聞人生活最後の奉公としてこの大事業に取り組むに至った」と、気概を表している。

フロリダなど辺境の地にも残る取材の足跡

新日米新聞社では過去に「全米日系人住所録」を発刊しているので各地の日系人との連絡網を備えていた。加藤はこれにもとづいて各地の日本人、日系人を訪ねて行った。しかし、それにしても、まだ州をまたぐインターステート・ハイウェイも建設がはじまったばかりのころであり東奔西走の複雑な旅だったとも想像される。

実際どのように走ったのか、実に知りたいところなのだがいまのところそうした記録には出合っていない。しかし、思いがけないところで彼の取材活動の一端を知った。

ここ数年私は、20世紀の初めにフロリダ州南部に日本人によってつくられたヤマトコロニーの歴史について調べているが、その過程で森上助次という人物が戦後家族にあてた膨大な手紙のなかに加藤新一の名前を見つけた。

このコロニーはニューヨーク大学を卒業した酒井醸をリーダーとする日本人によって建設された。森上は数少ない日本人として戦後も現地に残り、晩年地元に土地を寄贈、これがもとでいまでは立派な日本庭園などができている。加藤は、日本人にはあまり縁がないように思えるこの南フロリダで暮らす一世たちを確かに訪ねてきていた。

1961年1月の手紙で森上は「加州羅府新日米新聞社の主幹加藤新一氏」が「日米修交百年祭を記念する全米日系人発展紳士録を発行するため」に来訪し、酒井醸の写真を借りたいと頼んできたと書いている。森上もインタビューを受けたようで彼については本書の「第二十章 フロリダ州」のなかに詳しく出ている。

「従来収録されたことの無い辺境の地域まで含めた」と自ら言っているように、加藤は同様に全米各地で1世、2世を訪ね歩き、聞き取りをしたり資料を集めていたようだ。カリフォルニアについてはこれまでの付き合いから情報は、各地の有志の協力などにより集められたようだが、遠方の情報はまさに足で稼いで得るしかなかったはずである。各地で暮らす登場人物の固有名詞の数をみると恐るべき情報量である。

また、取材、編集、印刷をわずか1年半、昼夜を問わずの作業で完成させたというところも驚く。しかし、短期間で収集した膨大な情報について検証するのは不可能であり、また漏れている情報はもちろんある。その点については、加藤も重々承知で、「すべての本は修正されるためにある」という言葉を引用しながら、本書が「将来に於いて何人かがこれを修正し、一層よきものとすることを期待するものである」と謙虚に語っている。

海外における日本民族の苦闘と発展とともに、その背景にある米国民主主義の偉大さを見てとってほしいとも加藤は願う。

だが、彼とアメリカとの関係は実は複雑なものであった。原爆が投下されたとき、中国新聞の報道部長として広島市にいた彼は凄惨な光景を目にした。そして被ばくよって弟と妹を亡くした。(敬称略)

© 2014 Ryusuke Kawai