Read Part 1 of Vol. 10: Japanese Americans in Oregon >>

Oregon is located between California and Washington. Japanese immigrants in Oregon, also written as Chushu in kanji, have also been subject to anti-Japanese movements and attacks from white society. The "Centennial History" summarizes the history of anti-Japanese sentiment by era. The outline is as follows:

As an early example, the Asiatic Exclusion Society was founded in 1910 in the Hood River area, where Japanese agriculture was thriving, and anti-Japanese movements were carried out in newspapers and speeches. Anti-Japanese bills were also submitted to the state legislature and were eventually passed.

Anti-Japanese riots in Toledo

In 1925, a major anti-Japanese violent incident occurred in the Pacific coastal city of Toledo.

"A mob of up to 200 people, carrying the American flag at their front, attacked a camp of Japanese workers at the Pacific Spruce Lumber Company factory in Toledo, Central California. Sensing some unrest in advance, they inflicted serious and minor injuries on five guards who had been dispatched by the company. The violent group then burst into the building and demanded that the Japanese leave immediately. They then forced the Japanese into cars and abducted them to a convenient location on the railroad. A total of 31 people, including 25 Japanese men and two women and four Philippine nationals, became victims of this unlawful act."

This was in protest against the employment of Japanese people by lumber companies.

In response, the Oshu Japanese Association sent a letter to the governor of the state, requesting that the mob's malicious propaganda be rectified. They also reported the facts to the Japanese government and requested appropriate measures. Furthermore, four victims filed a lawsuit seeking damages. The plantation was allowed to accept the lawsuit, and the court ordered the plantation to pay $2,500 in damages.

As war drew near, the abolition of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the United States and Japan caused concern for Japanese businesses, and measures were taken to have various businesses run by first-generation Japanese take over, as far as possible, by second-generation Japanese who had become American citizens.

Post-war Japanese American recovery was slow in Portland

Before the war, Portland was home to 1,680 Japanese Americans and was a thriving city with a large number of Japanese activities in the areas of commerce, religion, education and journalism. However, immediately after the war, the Japanese community shrunk dramatically.

"The recovery after the war was extremely slow, which was a little sad."

The reason for this is said to be that the city government treated Japanese people harshly, making it difficult for them to resume their former businesses, and leading to a sharp decline in the number of people returning.

Another factor was the collapse of the levees on the Columbia River, which caused damage to the city of Vanport, which was densely populated by Japanese people, resulting in the loss of property and casualties.

"The forced eviction caused great damage both materially and mentally, and they had spent most of their money living in the new residence for three and a half years. They had finally returned to their old home with joy as the law was lifted, but the hardships of the anti-Japanese city government had made it difficult to get their work started. On top of that, they were faced with this terrible disaster that seemed to fall from the sky. They found themselves in a double predicament, with the worst of it all...."

However, the Japanese community gradually began to develop again. In 1950, Portland's population was about 460 people, but by 1960 it had grown to about 1,990 people.

A Japanese man described as having had a "strange life"

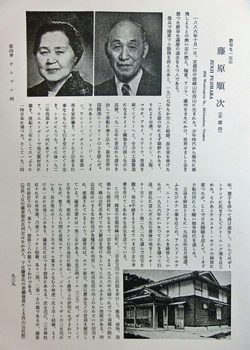

The chapter on Oregon's Centennial History also introduces many Japanese and Japanese-American individuals living in Oregon. They have a variety of titles, such as "farmer," "apartment owner," "grocery store owner," and "originator of women's clothing." Among them, however, there is one Japanese person whose story is introduced under the rather unusual title "The Unusual Life." His name is Fujiwara Junji, a native of Mineyama-cho, Naka-gun, Kyoto Prefecture.

Indeed, when we trace the events in his life, we find that they are quite unusual. Below is a brief summary.

Mineyama Town is a town in the northern part of Kyoto Prefecture, in the center of the Tango Peninsula, where the Tango Chirimen business is thriving. Fujiwara was born in Mineyama in 1888. He was conscripted into the army, and after that he married in 1907, had a daughter, and then traveled to the Korean Peninsula at the age of 25.

He then traveled to Taiwan, the Philippines, Shanghai, Macau, Xiamen, Swatow, Hong Kong and Sydney, Australia, selling crepe fabrics manufactured by his younger brother. In 1915, he boarded a British ship from Hong Kong to go to America and arrived in New York.

From there, he worked in various jobs in the eastern United States, including New Jersey, Maine, Washington DC, and Boston, working in American homes and as a cook, before arriving in Chicago. In 1922, he came to Oregon and worked in lumber mills in Astoria and Westport, before returning to Japan after a 13-year absence.

In 1924, he returned to the United States with his wife and children and started a dry cleaning business in Portland. He then ran a hotel business, but the war broke out and he was interned at the Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho. After the war, he returned to the United States and started a hotel business again. He retired in 1956 and spent the rest of his life in Milwaukee, south of Portland.

They donated over 2 million yen to build a community center in their hometown of Mineyama, and when they returned home together, they were warmly welcomed by the entire townspeople. They have one son and three daughters. They have ten grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. They have had a strange, if very eventful, life.

(Note: I have used the original text as much as possible, but have made some edits. In addition, I have based the names of places on the way they are written in the "Centenary History.")

*The next issue will be " Japanese Americans in Idaho ."

© 2014 Ryusuke Kawai