I’m currently carrying out a Fulbright English Teaching Fellowship in Northern Vietnam. When I sit down to meals with my students, they are always surprised at my skill with chopsticks. I try to explain to them in broken Vietnamese: cha tôi là người Mỹ gốc Phi, mẹ tôi là Mỹ gốc Nhật. My father is African-American. My mother is Japanese-American. I’ve been using chopsticks since the day I was born. This always draws a wide-eyed smile of exhilaration across my student’s faces, as if I’ve shared some great secret with them.

In some ways I have. I self identify as Japanese-American and African-American. My grandmother, Akiko, met my grandfather Satoru, in Manzanar; the California “internment” camp Japanese-Americans were sent to during World War II. After the war, they married in Salt Lake City, and then relocated back to Los Angeles where my Obaachan (grandmother) worked as a librarian administrator at Beverly Hills High School, and my Ojiichan (grandfather) worked as a manager at a company selling comforters. They had three Sansei (third generation) children, my mother Janet, and my uncles Jeff and John.

My mother Janet grew up the Crenshaw area of Los Angeles, first surrounded by Caucasians, then a growing Japanese American community, and then a growing Black and Latino community, attending Dorsey High School. The Crenshaw area changed gradually, sometimes not so gracefully in race composition, and soon enough with education and work, my mother’s circle expanded. She eventually met my father, an African-American actor from Washington D.C, while working at the pre-eminent Asian-American theatre in California, East West Players.

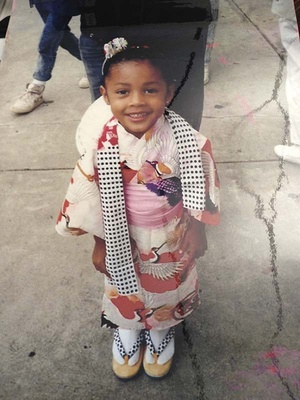

My Nikkei blood is strong, and its history and the culture naturally run through my veins. Whenever I see the big red circle on a white cloth I can’t help but grin from ear to ear, wondering if the Mitsui (my Japanese family) bloodline were farmers or merchants or perhaps samurai. While I have family in Japan, I strongly self-identify as half Japanese-American and half African-American. I am composed of a lengthy juxtaposition of customs, styles, languages, and histories. My hair is wild and curly, yet my eyes are almond shaped and close together. In the summer, my skin turns dark brown, but in the winter my light skin reinforces the fluidity of my mixed race.

I was raised as a Buddhist with the Venice Hongwanji Buddhist Temple in Culver City, attending obons, eating dango, playing taiko, and following the compassionate dharma of Amida Buddha. Before alzheimer’s set in about 6 years ago, my Obaachan spoke frequent and fluent Japanese to us, her grandchildren. I still have family in Japan and I felt personally connected to the 11/11 tsunami disaster as my uncle wrote to family, describing how my three-year-old cousin Miho slept fully clothed in the basement, ready to evacuate at any moment.

I chose to study religion in college because I wanted to further understand the stories and symbols at the center of people’s lives. In Vietnam, my race, nationality, language, and generation are a complete mystery and there are multiple hurdles to overcome as I share my identity here. This has proved both empowering and tedious as I am given the responsibility to explain who I am. I love playing the ethnicity guessing game—Indian, South American, Hawaiian, Filipino, Indonesian? No one knows of my Nikkei heritage and I feel an immense sense of pride in sharing this fact with everyone I meet.

Being Japanese-American and African-American means knowing how to make fluffy rice, recognizing the difference between karaage and black soul food, and gracefully navigating hair products at the supermarket. It means mixing yet equally preserving each half of my cultural and ethnic heritage by paying respect to my ancestors and knowing my history.

My father’s family is largely relegated to the east coast. Growing up on the west coast, my holidays were spent with the Japanese side of family. I have great-aunts who still speak Japanese as a first language, and baby cousins who are being raised bilingual. This reminds me that Japan will always be in my family’s heritage no matter how Americanized I am. Before every meal, I silently bow my head and say to myself, namoamidabutsu itadakimasu (thank you for the delicious food we are about to eat)! It reminds me to give thanks for Buddha’s teachings, and to the culture that continues to shape who I am.

Now that my Obaachan is 91 years old and burdened with significant memory loss, I feel a responsibility as a Yonsei to keep the customs of my heritage alive. For me this means learning how to set-up the obutsudan (Buddhist altar), make ozoni (a yummy soup with rice cake mochi) for New Years, and never forgetting the history of my ancestors and other Nikkei. Sometimes, when I wake up early, I’ll go outside and watch my mother tend to her bonsai plants. While she loves gardening, my father’s hobby is building Japanese fountains. I look at the two of them working with their hands and I feel so very grateful to be Japanese-American and African-American—it is an incredible honor and gift. I am an elite member of a secret club; it is where I learn to put furikake on my rice, enjoy the sweet tastes of ponzu and shiso, and the every-day Japanese aesthetics that make life so pleasurable and amazing.

© 2013 Tani Mitsui Brown