I was barely a day old when my Nisei parents had a big fight over me. I had just been born in Honolulu and, after deciding that “Alden” should be my English first name, they argued over what my Japanese middle name should be. My father wanted “Makoto” to honor a priest in Hiroshima whom he respected, but my mother was adamantly opposed. After much wrangling, my father eventually prevailed and “Makoto,” which means truth or sincerity, became my middle name.

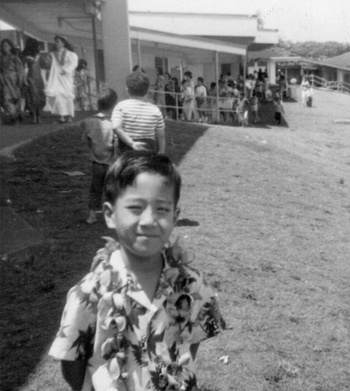

I first found out about that fight when I was in kindergarten and was attending after-school Japanese-language classes. I had just learned the kanji for “Makoto” (誠) and was struggling to write the 13-stroke ideogram. The order of the strokes wasn’t intuitive at all and the kanji itself looked so asymmetric and ungainly. I was frustrated with my penmanship, and that’s when my mother told me that she didn’t want my middle name to be “Makoto” but Dad had insisted. It was a surprising thing for me to hear because my parents rarely, if ever, aired their grievances with each other to their children, so of course I was curious to know more.

Mom explained that our last name, Hayashi, is a single kanji character (林 : two trees standing side by side) so she didn’t want my middle name to also be a single character because then people might mistake me for being Chinese. At the time, I found her concern rather odd—after all, we were first and foremost Americans and anybody in Hawaii would know that I was of Japanese descent simply by my last name. So I didn’t put a lot of thought into what my mother had told me that day, but her words did stick in my mind.

Years later, when I was just out of college and newly employed, I became close with one of my co-workers who had emigrated from Hong Kong. When I wrote my name Hayashi Makoto (林誠) in kanji for her, she told me that it would be pronounced “Lum Sing” in Cantonese, which then became her pet name for me, especially when I screwed up on something. “Lum Sing,” she’d chide me, “you should know better than to make a mistake like this!” I liked when she used that pet name because it always softened the blow of whatever criticism she had about my work, making it so much easier for me to hear her words without getting defensive. But when I told my my parents about this, my mother was not amused. “Why in the world would you let her call you ‘Lum Sing’?” she asked in disbelief. “Doesn’t that woman know you’re not Chinese?”

“Of course she knows I’m not Chinese,” I said, “but it’s just her nickname for me.”

“But what if other workers think you’re Chinese?” my mother asked, a look of consternation and deep concern in her eyes.

I had never thought of my mother as being racist, although my brothers and I did know that our parents had a strong preference that we marry other Nikkei. But some of my Sansei cousins had married Chinese Americans, as well as people of other ethnicities, and my parents had always embraced those members of our extended family. Plus, growing up in Hawaii, I had so many Chinese American friends and not once did I hear my parents express any racial unease about those relationships. So I was shocked at my mother’s seemingly anti-Chinese sentiment.

Only now, as I enter my elderly years, do I finally understand what my mother was trying to tell me all those many moons ago. As was often the case, the mystery of her behavior could only be unlocked by having a better grasp of her painful history.

During World War II, not only was my mother and her family shipped from Hawaii to the Jerome concentration camp in Arkansas; they were also subsequently deported to Japan in a hostage exchange. This was in 1943, during the middle of the war. They ended up settling in Iwakuni, the town next to Hiroshima, and, given the bloody, bitter battles being waged across the Pacific between the U.S. and Japan, my mother and her siblings tried to hide their Western roots as much as they could, so they shed their English first names and went by their Japanese middle names. Still, they were teased and bullied in school.

Even after the war, when my mother had married my father and moved back to Honolulu, where she had been born and raised, I believe she still harbored fears that, at some point, she might be deported to Japan again. And that’s why she didn’t want any of her children to have a name that could be mistaken for Chinese because, if we were all expelled to Japan one day, she would want us to fit in as much as possible, just as she had to during World War II. So I would no longer be Alden Hayashi; I would become Hayashi Makoto; and she worried that that would raise questions about my racial ancestry. That is, people in Japan might mistakenly assume that I was Chinese because my full name had just two kanji (林誠=Lum Sing).Today my mother’s fears might seem foolish, comical almost. But my brothers and I were born in the 1950s, just as the Korean War was ending and the war in Vietnam was ramping up. Should any conflict in Asia spread, could anti-Japanese rhetoric rear its ugly head again in the United States? And if the U.S. could deport my mother and her family once, why couldn’t the government do it again?

Thinking about all this, I can’t help but feel such compassion for my mother. Because of her traumatic past, something that should have brought her joy—the naming of her son—had instead vexed her mind in such distressing ways. Although she had very much adopted a shikata ga nai (it can’t be helped) attitude toward the past, she could never really escape its deep reverberations. She passed away in 2013, after having had a full and I believe satisfying life, but I do wonder if she ever felt completely secure being back here in the United States, or whether there was always a lingering anxiety of that other shoe dropping, that she and her family might again be deported. Some mental scars never leave us, and as my mother entered her twilight years and dementia began to impair her mind, she often had difficulty keeping those mental demons at bay.

As for me, I have grown to love my middle name and have always insisted on including my middle initial in my byline. The added “M” might seem like an affectation because, really, how many Alden Hayashis could there be? (Interestingly, though, I did learn through Facebook that there is another Alden Hayashi, though he lives in the Philippines.) But including my middle initial is important to me as an author because the “M” indicates what I try to seek in my writing—the truth, sincerity. Moreover, I now treasure my middle name because it symbolizes the battle my parents fought over me, in which my father’s optimism of the future had won over my mother’s persistent fears of the past. And my middle name’s complex history has made me realize that, just as the past continued to live in my mother, so has her past always been with me, literally from my very first days on this earth.

© 2024 Alden M. Hayashi

Nima-kai Favorites

Each article submitted to this Nikkei Chronicles special series was eligible for selection as the community favorite. Thank you to everyone who voted!