*Continued from part 1 , the following story is told by the author's father, Masao Nakachi, from a first-person narration.....

I had arrived in Lima in 1926. I was only 16 years old and I looked smaller in size than the Lima residents who frequented the café where I worked. I didn't understand anything that was happening because I didn't know the language. I worked hard day and night to learn.

I didn't know about politics, but in the cafe where I worked, it was the main discussion among the customers and, within a year, I dared to give my opinion and appear to be an expert on the subject. At that moment it didn't seem like a tremendous dare to me. He was still very young.

Those were the times of Leguía. Leguía had won the elections in 1919, but had organized a coup against President Pardo, claiming that he wanted to prevent him from becoming president. The stately city was full of enthusiasm, gossip and criticism. Lima was bustling with ideas and alive with politics.

His first years had been very good. He knew how to take advantage of the wear and tear of the “old” parties and approached politics with a business mentality, with the idea of financing national development from his own resources and internal savings.

In the atmosphere of Lima's cafes, there was already talk of President Leguía's plans to ensure his re-election and stay in power. One heard of large foreign credits. It was heard that he had not reactivated the productive apparatus and that the external debt had increased, which favored his relatives and certain sectors of the middle class, and that what was collected was not redistributed efficiently among the most disadvantaged. They maintained that the progress they seemed to have was an illusion maintained with the idea of foreign credits to come.

In 1930 Leguía fell, overthrown by Sánchez Cerro, and the coffee discussions were right about one thing: the Peruvian State was still as weak as before.

But, everyone agreed that the city of Lima was much more beautiful and stately than before. His government had coincided with the commemoration of the first centenary of the Independence of Peru (1921) and the victory of the Battle of Ayacucho (1924). The foreign colonies in Peru had made beautiful gifts to Peru. The most beautiful monuments, avenues and buildings that make Lima proud date from that time. The Manco Capac Monument in La Victoria was donated by the Government of Japan and the old National Stadium (which is no longer the same) was a gift from Great Britain.

The cafe where he worked was in the Left Hive. It was between Plaza San Martín and the University Park. Plaza San Martín was not what it is today. There were no buildings around. In the square there were four fountains of crystal clear water, from which soft, whispering sounds came out, adding freshness to the well-kept gardens and the people who sat to rest on the shiny marble benches.

In the distance you could see the Hotel Bolívar to the right and the Teatro Colón to the left. Elegant carriages and cars stopped in front of its doors. Ministers, Ambassadors, Princes, and even some Kings came and went. At dusk the ladies went out for a walk in their elegant dresses, always with gloves and hats, protecting themselves from the sun with finely decorated umbrellas. They never went alone. They walked at a slow pace, talking and laughing softly. There was no shortage of young people with their lip-smacking compliments full of poetry and mischief of course.

Some nights of the month, the Teatro Colón was lit up and filled with people, dressed very elegantly, to enjoy famous international plays brought to Lima.

Very close was the University Park. The German Government had given the tower and clock of the University Park as a gift. Every hour I could hear their chimes. Many people gathered in the Park at noon to listen to the ringing of the bells and the National Anthem that came from the Tower clock and could be heard from far away. I liked going to University Park.

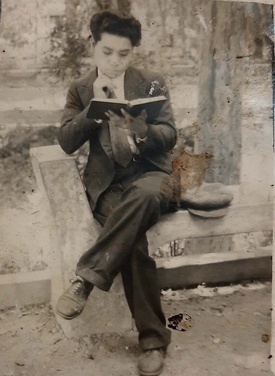

The Mansion of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos was there, with its large open wooden gates, through which I could see its gardens and mosaics, its railings, and its classrooms. There were always groups of college kids outside in the park. They all wore suits and ties and filter hats, one or two books under their arms, a smile and a compliment for every pretty girl who passed by them. Some more serious ones read and studied under the shadows of the trees. How I longed to be one of them!

Every night as I fell asleep, with a book on my chest and great hopes in my soul, I could hear the chimes of the University Park clock. And, in the stillness of dawn, the clock woke me up so, so, so, every morning. Sleepy and cold, I dressed to head to the Central Market and start a new day.

At that time you had to walk to the Central Market. There were no buildings or shops, just vacant land. At that time there were few people and I could enjoy the tranquility of the walk, although I had to do it at a brisk pace.

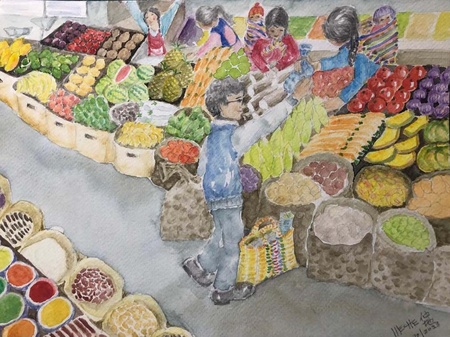

As I approached the market, the atmosphere changed. From far away you could hear and feel the bustle of the people. There were no paths or tracks. You had to walk carefully because the water was running along the edge of the road. You could hear the noise of the carts, the thud of the packages falling to the ground, the shouts and voices of the people.

- Caserito, casirito...let's buy this, fresh and cheap, said the saleswoman showing her merchandise.

I looked, touched and squeezed each one of them to see if they were telling me the truth. I pretended to be uninterested and as if I was going to the other position.

- Chinito... look, play this one... It's very cool and cheap. Come on then.... how far have you been today?

- Well then...Give me 5 kilos...how much is it?

- Just 50 cents...

- No, no, no...very expensive. I'll give you 20 cents.

- Now, now... I'll give you your yapa, and you can take it for 25 cents.

- He wraps it well and puts it in my sack.

At the Market I learned to haggle, to know how to choose the best, many words in Spanish and some useful phrases for the daily life of a small immigrant.

- Shit...!, I muttered under my breath when the full sack weighed so much that my back and arms hurt and the blocks seemed longer than ever. Or when everything went wrong for me.

- Damn...!, when someone bothered me a lot.

- Don't fuck with me...!, was the only phrase that sometimes kept away those who tried to annoy me.

Some days I thought they were good in coffee. The Left Hive was in a strategic location in Lima. Some clients were important and most were not so important. Some were regulars for a while. I especially remember a very quiet English gentleman. He was always very elegant in a suit and white shoes. He sat at a table and read the newspaper while drinking coffee. One day he walked into the cafe and said:

- Buenos dias ...

Since then I never stopped learning English. He left the English newspaper on the chair for me. I bought a small dictionary and every night, despite being sleepy and tired, I tried to learn a word or a phrase.

On Sundays I went to Sunday School which was next to the Congress Building, which was under construction at the time. There I noticed for the first time, sitting on the first benches, a young girl who fascinated me with her beauty. I looked forward to Sundays and I think I didn't miss church, just to see it even from afar. I would sit in the back and try to listen to the pastor's sermon attentively, although I would nod off from time to time, when it got a little boring. After a while the young girl and her companions no longer came to church and with great sadness I found out that she had gone to Huancayo to take care of her sick mother.

On my days off I went for walks. I usually went to University Park. I liked mixing with the students, sitting and reading a book, talking and making friends. Sometimes I went up to the Plaza de Armas to see the Government Palace, which had been rebuilt after the fire of 1921.

But, I liked walking towards the sea more. It went down, passing the Palace of Justice, with its large pillars and staircases, to the Museum of Art, with its exquisite architecture, gifted to the city by the Government of Italy. It continued along Avenida Leguía (today Av. Arequipa) or Avenida Brasil, recently opened in the Leguía Government. To get to Chorrillos or Barranco or Callao I took the tram. I would sit on the tram lulled by the soft purring and rocked by its many stops and starts before reaching its final station.

The tram that came from Chorrillos stopped at Plaza San Martín. Many cadets from the Chorrillos Military School went down there. One cadet in particular came frequently to the cafe and we became friends. Many years later I heard from him again. It was General Velasco Alvarado who years later became president of Peru.

The exhausting and slavish work and the climate of Lima, humid and cold in winter, did not suit me very well. I was coughing a lot and my chest was wheezing. The apothecary had given me medicine that didn't help me at all. I became the owner of a herbalist who sold me a bottle that relieved my cough, but anyway I wanted to see a doctor. One day I heard about a new hospital from some medical students who came to the café.

- Where are you doing your internship?

- At the Arzobispo Loayza Hospital... It's not far from here

- Wasn't it just inaugurated? They tell me it is very nice and big...

- The nuns are very strict. And the doctors are the best.

On one of my days off I went to the Loayza Hospital, but they didn't let me enter. They told me it was a women-only hospital.

Finally, the seven years of my employment contract had come to an end, but my cousin didn't want to let me go. After being the first to wake up and the last to sleep for seven years, feeling enslaved and overwhelmed, I had no choice but to demand my compensation and ask him, for my health, to let me go. I had heard that to cure their lungs people went to Jauja where there was a good sanatorium in the mountains.

I don't remember if I really felt bad and exhausted or I just wanted to get out of there, but I didn't hesitate to pack up, buy a ticket and go to Jauja with my savings. I only knew that Jauja was very close to Huancayo, and my dream was no longer in Lima but there.

I remember the long train ride, its monotonous sound accompanying the beating of my heart and the rebirth of longing and dreams in my soul... again.

© 2023 Graciela Nakachi