A few days ago, after many years, I passed by Jishuryo (now Santa Beatriz Early Education Center), my old primary school. The large entrance gate to the school was closed. I saw that the gray wall that surrounded it is still there, but above it no longer protrude, as before, the crowns of pine trees or the tall stems and leaves of the bamboos of the entrance gardens. The Jishuryo from the fifties to the eighties that I remembered, inseparable from the Nakachi family and Victor, the incomparable goalkeeper, with great sadness, were no longer there.

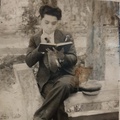

Just as Nakachi-san was more than a cook, Victor was more than a porter. Both were caretakers of the school and its students in many unequal ways.

Víctor came from very far away, but without fail he was early every morning to open all the classrooms, the Administration, the Teachers' Room and the large gate. Then he waited for the arrival of the cars that brought the children. As they arrived, he would let them in without allowing anyone distracted to stay outside. When the bell rang he closed the gate.

With our beige aprons over our uniforms (the girls, in blue pleated skirts and jackets with sailor collars and ties, and the boys in lead suits and white shirts) we formed lines in the first courtyard for morning exercises. We were formed according to the year we were in and the size. The little ones were in the back. The best student, selected by the director, was placed in front to guide the exercise. I turned on the speaker and the taiso radio started: ichi, ni, san...

Once all the exercises were finished, we headed towards the classrooms. The rooms were spacious, with high ceilings and large windows. The doors and floors were dark brown and the walls cream. Never, in all my years, have I seen dirty or defaced walls. Sometimes you could see in some folders the blurry name of a student who wanted to leave the mark of his time in that room. Only the chalk splashed on the floor when erasing the blackboard.

When the specks were very loaded with chalk, they told us to shake them outside, on the metal grates that were used to clean our shoes before entering the room. We sat on individual wooden tables, the boys on one side and the girls on the other side. When the teacher entered, the designated student would stand up and say out loud:

–Kiritsu! –and we all stood up at the same time.

– King ! –and we bowed to greet.

We had ten minutes of recess between each class and a long lunch break from 11:30 am to 2:00 pm Most of us went out to play in the yard. The boys played in the second patio, which was dirt, and the girls in the first patio. The bathrooms were between the two patios. We usually went two by two: we asked our best friend to do ban , that is, to make sure the boys didn't get into mischief or open the door without realizing it.

The second patio was large. It was so big that the school's sports festivals were held there. The patio was dirt, which Víctor compacted and hardened every afternoon by watering it with the hose after classes. Towards the front there were two large rooms with their respective paths and gardens with trees that provided shade when it was very sunny.

To the right were the smaller rooms for older students, administrative offices, and storage rooms. There was a long path that ended at a door that led to the back of the school. Almost no one used it. Towards the back was the sandbox and the wooden horse, a long log on which, although dangerous, we liked to swing.

The first patio was my favorite. The halls and gardens surrounded the courtyard. The rooms were on a level with the patio and you had to climb some steps to reach a kind of porch, which connected two rooms, to enter. It had a wooden railing painted dark brown and a tiled roof covered its entire length.

A garden full of bamboos, floripondiums, cucardas and geraniums separated the four rooms. A larger garden, full of cypresses, bamboos and large pine trees, was seen on both sides of the gate separating the rooms from the outer wall. The tops of the pine trees could be seen from the street. In the garden on the left, a narrow path led from the patio to a side exit door. Between the Directorate and the classrooms there was another path that led to a long corridor that connected the side door with the school kitchen and the two rooms where the Nakachis lived.

Jishuryo was renamed “Santa Beatriz School” by order of the Peruvian government, an ally of the United States in the war against Japan. All Japanese schools had to change their names.

I spent my entire childhood in Jishuryo. We played in their yards and gardens during the long lunch hours. We played hide and seek, mama goto (to the little house), we looked for the turtle that was hiding among the bushes to torment it with our childhood games, while we watched with curiosity how it hid its head inside its shell or its fruitless efforts, desperately moving its four legs, to recover its position when we put it on its back. Then, sadly, we would caress his head and offer him lettuce and vegetables that we had asked for from my father, Nakachi-san.

The trees provided shade on the steps, sidewalks and railings, where we sat to play, talk or rest. They gave freshness to the rooms where we took classes, sleepy and sweaty, after having run around for more than two hours. How many patches they had to put on my brother Lucho for falling from the branches of the trees he was trying to climb! Under the shadows of the trees we made our First Communion, we competed in sports festivals, we received our awards at the end of the year, and we graduated from primary school.

During the long hours of recess, the children played in the second dirt yard, where the soccer goals, the basketball basket, the wooden horse for swinging, the sandbox, and the guard dogs' house were located. We girls used to stay in the first courtyard playing jax , mama-goto (to the little house), let the king pass by, hiding, motionless, bata (a kind of softball without a bat).

We usually played bata with mixed teams when we had to do PE in the afternoon, and we changed into our gym uniforms: white shirts and baggy black shorts. To do Physical Education, the children did it in the second patio and we did it in the first patio.

By asking permission we could play in the sandbox. With small buckets we carried water to wet and mold the sand. We built castles, molded figures, dug tunnels. With or without talent, we had a lot of fun until a ball from the children playing soccer ended our creation amid cries of protest and apologies. The teacher on duty always came to calm things down.

The dining room was between the first and second patio in front of the bathrooms. It was spacious, with large windows between the two sliding front doors. The ceiling was high, like all old buildings, and the floor was of gunmetal-white mosaic with green trim. Tables and benches made of old, solid wood were arranged side by side, in two long rows in the center.

Other narrower tables lined all the walls of the dining room. At the center tables we sat facing each other, but at the other tables we looked toward the wall or the window. To the left of the entrance was the little table, somewhat lower, where the pots from which the dishes were served were placed.

Becoming a fifth year was a long-awaited honor in Jishuryo. The fifth graders, in turns, helped set the tables, seat the children, and serve the tables. When the bell rang, at 11:30 in the morning, we all ran out to the patios. One or another peeked through the dining room door to see if the food was already served. They watched, anxious and hungry, Nakachi-san and Victor put the full plates on the tables.

When time was short, formality was lost a little and the cutlery and plates were passed from hand to hand among all the students who wanted to help, flying to the tables. Nakachi-san supervised:

–This one has very little, we have to put more rice... This one has no meat... –and I added what was missing.

The fifth year students served the table with formality, seriousness and importance. Sometimes they allowed some of the little ones to serve dessert. Others watched, waiting to run to ring the bell to form lines and go in to eat. Hmmm... So hungry! When someone shouted that he was ready with:

–Now... you can ring the bell!

Several had a race to see who would win to ring the bell.

After washing our hands we lined up to enter, showing our hands to the teachers. If he hadn't washed himself properly, he would take him out of line, send him to wash, and leave him at the end of the line. We entered in an orderly manner, sat down and the teacher on duty said, with everyone in unison, The Lord's Prayer. And to eat...

–Itadakimasu ...! –we exclaimed in unison.

The hubbub was tremendous. We ate and talked. The fastest and gluttonous ones raised their hands to repeat. Victor or one of the older ones would come over to serve him a second dish. And so they continued raising their hands until, seeing the empty pot, someone shouted:

-There is no more...

We had to wait for everyone to finish eating, then we left in an orderly manner. Once at the door, we ran to the patios to start playing until the bell rang for the start of afternoon classes.

After all the students who were staying for lunch left, which were the vast majority, in line and in order, some sad for not having managed to have the okawari, but all happy for being able to play a lot until the start of the school classes. Later, the tables were cleaned for the second lunch shift at school. On this shift there were the older students on one side and the teachers on duty on the other side. Lunch for them was better.

The teachers ate calmly, with a long after-dinner meal. From there they could hear the excitement of the children in their games and the older students on duty, from the table where they were, could watch and take care of the younger ones. Occasionally lunch would be interrupted by a child crying from a fall or bump that required attention. And lunch ended with a light sigh.

© 2024 Graciela Nakachi Morimoto