I feel I have paid many times over for the position I took at Tule Lake.

Certainly, you don’t go around telling people you spent time at Tule Lake during the war.

You try to push that back somewhere and not think about it.

You try to block that part out of your life, but you have to live with it.—Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Swimming in the American

Out of approximately 125,000 names of former detainees listed in Ireichō, more than 12,000 of them were once shunned and segregated at the often-maligned Tule Lake Segregation Center. For those who felt they needed to “block out” that part of their lives, this sacred book duly honors them for their rightful place in history as individuals who challenged their imprisonment by refusing to go along with U.S. government actions that caused many, even other Japanese Americans, to brand them “disloyal” or “troublemakers.” Ireichō has brought many Tule Lake families and others out of the shadows to mark their ancestors’ names and pay tribute to the hardships they endured.

A complicated history surrounds those held at the Tule Lake Segregation Center, often referred to as the “worst” of the ten concentration camps for its maximum-security imprisonment of people, some of whom were beaten and held in a stockade for up to 11 months. Out of 18,000 people held there, two-thirds had answered “no” or refused to answer questions 27 and 28 of the highly controversial “loyalty” questionnaire forced on all detainees nearly nine months after the camps were formed. These two flawed and misleading questions asked Nisei (often with families) already imprisoned in concentration camps to serve in the military and forswear allegiance to a country many of whom had never set foot on.

It took someone like playwright/writer/poet/actor Hiroshi Kashiwagi to raise awareness of the plight of Tuleans by fearlessly speaking out about his own unlawful imprisonment, his segregation at Tule Lake, and his renunciation of American citizenship, at a time when it was unpopular, even shameful, to do so. Among the first Nisei to speak out about the Tule Lake Segregation Center, he became one of its most dedicated and fearless spokespersons. Whether in plays like The Betrayed or in poems like A Meeting at Tule Lake, he fought off critics who felt those who answered “no” were somehow lesser citizens.

As he wrote, “My position was this—why was I, an American citizen, thrown in prison without cause, without due process? Why were they questioning my loyalty? I was an American, a loyal American.”

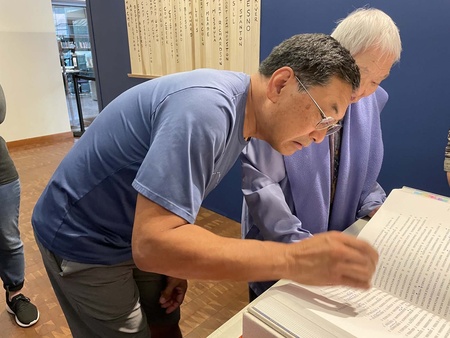

Kashiwagi died just shy of four years before he could mark his own name in Ireichō. In his honor as well as a tribute to other family members, Hiroshi’s wife Sadako (Nimura), sons Hiroshi and Soji, and Soji’s wife Keiko Kawashima, gathered to place hanko stamps on their names to symbolize the indelible marks they made in Japanese American history. Ninety-year-old Sadako traveled with her son Hiroshi from Berkeley, CA, to remember her husband of sixty-two years, as well as eight other family members who, like herself, were held in detention at both the Arboga Assembly Center and the Tule Lake Concentration Camp.

She made a point to call attention to her Issei father, Junichi Fred Nimura, whose eventual imprisonment at the Santa Fe Internment Center for so-called “enemy aliens” is an important part of the resistance story. Her father’s history is unique in that he was already imprisoned at the Tule Lake Segregation Center when picked up by the FBI and further imprisoned apart from his wife and six children. Only about ten years old when it happened, Sadako has a clear memory of her father being hauled away while she and her friends were playing a game between the barracks. The only one in the family to see it happen, she vividly remembers her fear of not knowing what was going to happen to him.

He ended up being sent to the alien enemy detention facility at Sharp Park in northern California, another of the 75 sites memorialized by Ireichō, and then transferred to another center run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, this one in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He was separated from the family for 18 months.

Her father’s story is one of many that depict the plight of those who resisted the government’s imposition of the loyalty questionnaire and the subsequent draft. According to Sadako, her father spoke out at an army recruiting meeting, saying that people were “fools” to volunteer for the army after being put in a camp where one’s loyalty was already being questioned.

She believes that the reason her father was subsequently picked up by the FBI was the obvious result of someone within the camp reporting her father to the authorities. In the divisive atmosphere of Tule Lake, where pro-Japan factions were imprisoned side-by-side with people considered “inu” or informants, increased turmoil was inevitable.

Although the Nimura family did not end up in Japan partly due to the protestations of her two brothers who were born and educated in the U.S., the threat of renunciation and deportation hung over many at Tule Lake. Ultimately, more than 5,500 people ended up renouncing their American citizenship, and one of them was Hiroshi Kashiwagi.

Although the elder Hiroshi spoke relatively openly about segregation at Tule Lake, for many years he was still reluctant to talk about his misguided application for renunciation when he was clearly loyal to the United States. As Sadako explains, “He was pressured from a family friend and was sorry the minute he did it.”

Confronted with pro-Japan factions at Tule Lake and even by his own brother, Kashiwagi wrote later that he “thought the problem would go away” and his renunciation was a result of his “refusal to face reality.” He turned to attorney Wayne Collins1 for help, and Collins, along with the backing of the Tule Lake Defense Committee, ultimately filed lawsuits to get citizenship back for him and more than 5,500 others who renounced.

While marking the family names of eight family members all imprisoned at Tule Lake, descendants Soji and Hiroshi spoke about their own reluctance to speak up until adulthood. As a playwright himself and executive director of the Grateful Crane performing arts group, Soji admitted that it even took him several years to attend his first Tule Lake Pilgrimage. As he explains, “Deep down, it was probably something that I didn't really want to face or see.”

Despite his father’s outspokenness, Soji had his own demons to overcome. When he finally decided to go for the first time in 2006, he thought it important to be there with his mom and dad. Since then, he says he “slowly came around.” “I had a deeper understanding of what the resistance was, what it meant. Instead of being a shameful thing, it became a sense of pride that they stood up for their rights and rights for all Americans.”

His younger brother Hiroshi nodded in agreement about the deeply buried shame now turning to pride. Along with Soji, Hiroshi now also volunteers as a bus monitor for the Tule Lake Pilgrimage. He also participated as one of the many who collected soil at the 75 detention centers that was used as material evidence of incarceration in the frontispiece of Ireichō.

On a hot summer day, Hiroshi drove to the Arboga Assembly Center in Marysville, the makeshift temporary camp where his mom and dad were first sent before going to Tule Lake. While there to collect soil, Hiroshi was surprised to see his father’s portrait and words looming over the newly built Arboga memorial. The younger Hiroshi did not expect to see his father’s face there, but he realized his namesake’s prominence as a resister who in many ways became the face not only of Tule Lake but of all the camps.

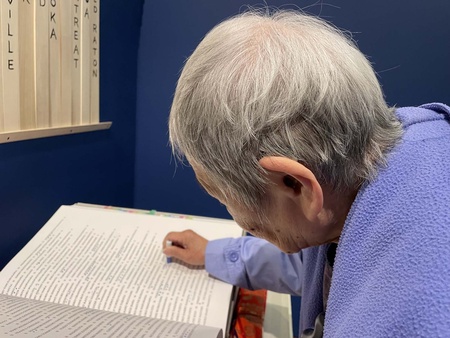

The Kashiwagi/Nimura families share in the celebration of all those who resisted while incarcerated. At Ireichō, they joined together to stamp the names of the Sadako’s parents, Junichi and Shizuko Nimura, as well as her brothers Nobuya and Taku, and sisters Hisa, Tomiye, and Shinobu (Jean). After marking her beloved husband Hiroshi’s name, Sadako paid a final tribute to him by returning to the sacred book one more time to make sure that the delicate stamp she initially placed could be seen. He was “honor bound,” she says, and with those words she summarized the actions of the many like him who resisted.

Note:

1. Poet/playwright Hiroshi Kashiwagi is featured in the film, ONE FIGHTING IRISHMAN, a 30-minute documentary about the efforts of attorney Wayne M. Collins to regain citizenship for those who renounced at the Tule Lake Segregation Center.

© 2023 Sharon Yamato