It’s hard to imagine anyone traveling to Cuba and coming back unchanged. It’s a place that has withstood the extremes of enormous wealth and poverty, slavery and revolution, and Soviet aid and the U.S. embargo.

Despite these historic ups and present-day downs, there is a vibrancy in the streets, culture, and people that is intoxicating. Streets overflow with pulsating music, enticing dance, colorful cars, and ubiquitous art—all despite crushing poverty that has only gotten worse due to and since the pandemic.

I can’t help but think that we could all learn something about finding joy in life if more people could visit Cuba. Sadly, the restrictions on tourism that were lifted by Obama in 2016 were reinstated in 2021 for seemingly incomprehensible reasons, one of them being that this peaceful island with no guns and little crime has been labeled a “terrorist” country.

We were fortunate to get insights about this island country from our incredibly well-read and informed 38-year-old Cuban guide, Rubén Javier Perez, who was first to point to the long gas lines that stretched for blocks and could last for days. There were also long queues that ended up at financial institutions where valuable American dollars could be converted to Cuban pesos.

At the same time, he led us into small bars where recorded or live music played while anyone from the street was invited to join to dance or sing—whether they had money to buy a drink or not. Joyful music and dance seemed to override any inconveniences.

He told us that because most Cubans make only $25 a month, many trained professionals like doctors or dentists end up working in restaurants or as tour guides to earn as much as $250 a week (barely a living wage here). It became understandable why many Cubans are tugging at tourists to hand over precious U.S. dollars.

However, despite increasing numbers of beggars in the streets, we were told that there was virtually little or no crime, and that our belongings were safer in Havana than in Miami. When I went running in the pre-dawn mornings with only a few people and cars in the narrow streets, I never felt threatened or afraid of being mugged. Though I received several stares (clearly for being a running turista), whenever I said hello, I received smiles and buenos dias in return.

Rubén, the son of a Cuban diplomat who ended up in his home country and educated at the university as a historian, also gave us a taste of the country’s turbulent history. After having gone through centuries of Spanish rule (now only evident in the magnificent but decaying neoclassical buildings), Cuba entered periods of upheaval, not the least of which were instigated by American intervention. With a history of U.S. efforts to back the unpopular Batista and later to assassinate Fidel Castro, you would think that the Cubans would hate Americans, but just the opposite was true. In fact, Obama is revered in this country for easing regulations on American tourism in 2016, which lasted until Trump reinstated stiffer ones in 2021.

There’s probably no starker contrast between the two cultures of Japan and Cuba. In spending eight days in Havana with two friends from Tokyo who are used to immaculate streets, we were immediately startled (and saddened) by the mounds of trash everywhere, left there because of crumbling buildings and scant trash service. It seems cleanliness is not a priority in a city with little water and inadequate supplies. Our Japanese travel companion found toilet paper nonexistent in a large deluxe hotel run by the national government. Since Americans are not allowed to stay in any government-run hotel, we were not privy to the actual accommodations, but we were told that even in five-star hotels supplies were spare.

Still, as a Japanese American tourist traveling with two tourists from Tokyo, we marveled at Cubans’ fascination with Japan, a country more than 7,500 miles from Havana (unlike Miami, a mere 90 miles away). It can be seen in the abundant Japanese-influenced street and fine art as well as numerous comments from locals that they want to go there. Our guide even had a manga character tattooed on his leg who was also pictured carrying a samurai sword.

We visited two renowned Cuban artists who had exhibited in Japan and whose work had clear Japanese motifs, in their case, haiku as art and an embellished geisha figure. It was hard to explain how this synergy came to be.

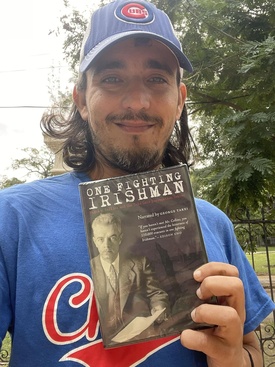

The highlight of the trip for me came at the end when I gave our guide a DVD of my film about attorney Wayne Collins and the Tule Lake Segregation Center (One Fighting Irishman). A few days later, he responded with a note that indicated his clear understanding and appreciation of the subject. His words touched me: “I feel so privileged to be probably the first person in Cuba that got to experience this documentary that feels fundamental to the legacy of the Japanese American community.”

After only eight days in Cuba, I felt a powerful cultural exchange that came from sharing our mutual histories of injustice. Just as he asked us to share thoughts about Cuba with friends, I’m certain he will share the story of the Japanese American incarceration with his. Understanding one another better became the best holiday gift of all.

*This article was originally published in The Rafu Shimpo on January 6, 2024.

© 2024 Sharon Yamato