To craft into a sacred book listing the names of 125,284 people of Japanese ancestry incarcerated at 75 World War II detention sites, it took inspired thought and meticulous research from its brilliant creative team. Led by Buddhist priest Duncan Ryuken Williams of the University of Southern California Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture, and book publisher Sunyoung Lee of Kaya Press, it was a book meant to be a living monument with Japanese spiritual elements among its essential building blocks.

In his seminal book on Buddhism in the camps, American Sutra author Williams tells the story of Buddhist Reverend Shinjō Nagatomi who provided the calligraphy for the kanji characters, I-Rei-Tō (Tower to Console the Spirits), engraved on the obelisk tower constructed in 1943 at Manzanar and surviving today as its distinctive landmark. According to Nagatomi’s daughter, her father practiced writing the kanji for hours “until the words seemed to dance off the paper.” The elder priest was aware that these engraved characters had to come alive on a concrete monument that would forever honor those who died while imprisoned in a U.S. detention camp.

Inspired by Nagatomi, whose son became Williams’s professor in Buddhist Studies at Harvard University, the former student would help create a different kind of monument based on two of those same kanji characters meant to “dance off the paper” to honor the dead. Instead of being made of concrete, however, this monument became a 25-pound book designed with the same loving care that went into the obelisk. It is also reminiscent of the Kakochō, an ancestral Buddhist temple’s record book that reverently pays respect to those members who have passed on, as well as Obon, an event that celebrates those ancestors.

The Ireichō team’s devotion to reverence consisted of many elements, among them the careful choice of design, binding, font, and paper. As Williams describes it, “We paid attention to making an unusually large-sized book, as large in dimension as the Gutenberg Bible, with over a thousand pages. The quality of the binding in particular needed to withstand thousands and thousands of page changes. We wanted it to look beautiful and reverential.”

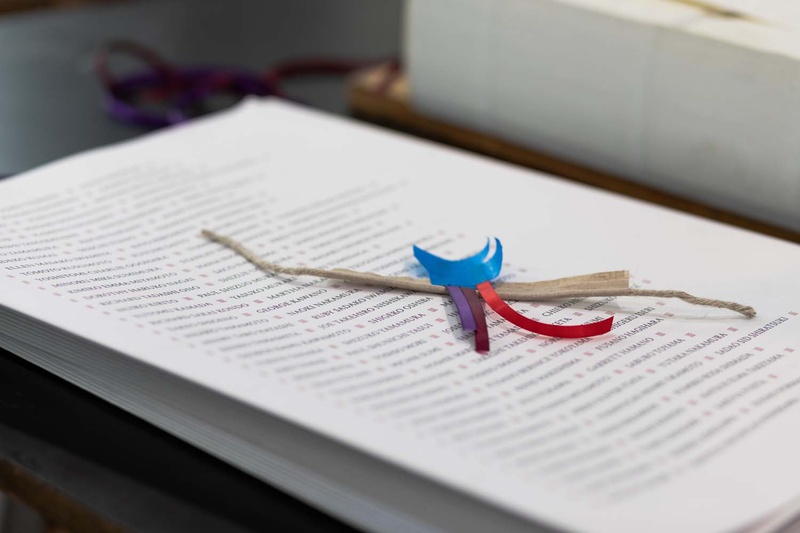

They accomplished this task by imprinting with a gold foil stamp the kanji characters on the cover, by inserting a delicate red symbol to separate names and symbolize bloodline, and by making sure names flowed across the binding in a meaningful way, not merely like a list of names in a telephone book. “We wanted names to read across the gutter of the page, not right side, left side, and that was one of the biggest design challenges,” explained Williams.

The other challenge was sequential, or the order in which the names would be listed. They settled on listing them in order of the person’s age at the time of incarceration, from the oldest, a 92-year-old woman, to the youngest, a baby born near the end of the war.

The process incorporated the Japanese tradition of kintsugi, i.e., repairing broken ceramic pieces by using gold to fix its parts, thus embracing imperfection while also making each piece more beautiful. Similarly, Ireichō embodies the repairing of history by honoring those 125,284 imprisoned people who were broken by a government that imprisoned them.

The reparative process is ongoing by inviting the public to put a small stamp, or hanko, to acknowledge each name while also correcting any errors. This process of materially changing the nature of the book emphasizes its impermanence, as in the Buddhist tradition of all things being constantly subject to change. According to Williams, “One of the goals of the project was to shift our understanding of what gives value to a monument, and that value is not measured by its permanence.”

Similarly, creative director Lee insisted that the soil that was carefully gathered by representatives from each of the 75 detention sites be embedded into the very materiality of the book itself to present a monument deserving of reverence. The opening and closing frontispieces that contain the soil were intricately designed and carefully constructed to make sure they were inset to encompass earth and fire—two of the five elements (earth, water, fire, metal, and wood) fused together in the ceramic pieces. The gold imprint of the 3 kanji characters represented metal, the blue hanko mark water, and the book itself represented wood/paper.

As much as Ireichō painstakingly pays specific tribute to incarcerated Japanese Americans, it is remarkable that neither of its creators, Japan-born Williams nor Korean American Lee, have personal familial ties to that history. In fact, after living in the U.S. for 35 years, Williams only became an American citizen two years ago, ironically on Juneteenth, the American holiday commemorating the emancipation of slaves. While protestors roamed outside City Hall, Williams realized that by becoming an American citizen, he suddenly took on the collective karma of the nation, a “deep racial trauma that transcends and transmits through generations” and extends not only to Japanese Americans but to other racial groups linked through common histories of suffering.

By working on the Ireichō project and honoring those to whom he became connected through a common language and history, he wanted to take something negative and turn it around. It was a conscious act as a new American citizen that would hopefully have a ripple effect. As Williams put it, “Maybe I can contribute something and then if I do something, others will join me.”

Clearly, others have joined in huge numbers. Starting with the core group of roughly a dozen staff members, there have been a host of volunteers, including innumerable colleagues and helpers who collected soil samples, clergy and community members who participated in the 200-person procession that announced the book’s arrival at the Japanese American National Museum, and thousands of people who have stood in long lines to make their marks on the book.

The work has only begun, with two future Irei projects still being developed, one a website with a searchable list of names (Ireizō) and the other a series of light sculptures containing the list of names placed at various sites (Ireihi). Like Ireichō, all are considered innovative yet mutable monuments to remember and repair the racial karma of the nation.

Considering the years of work that have already gone into the creation of Ireichō, including the massive work of finding and verifying all 125,284 names, one can’t help but wonder how Williams and Lee will survive the enormous work that lies ahead. Williams recalls the words of a Buddhist priest-instructor who warned him, “When you become a Buddhist priest you will have no more holidays.” With a knowing smile, he continued, “So you have to make every day a holiday.”

In the more than 30 years since becoming a priest, the Buddhist scholar has come to the realization that each day has to be treated as the most sacred and important day of one’s life. However, because there are no rest days, one also has to live each day as a kind of vacation that can be enjoyed.

With no days off in sight, he has persevered because of the conviction that “somehow it has felt right.” He has faith that this is something they are supposed to be doing. Judging from the tears of joy from those who’ve participated in the project thus far—from incarcerees to descendants to allies—there’s no doubt that the Ireichō team is doing something right. The energy created around the project has become its own monument, and that’s the karmic energy that keeps everything flowing positively forward.

* * * * *

Irei: National Monument for the WWII Japanese American Incarceration Launch

On September 24, 2022, the Japanese American National Museum hosted a private event to consecrate and install the Ireichō, a sacred book that records the names of over 125,000 persons of Japanese ancestry who were unjustly imprisoned in US Army, Department of Justice, and War Relocation Authority camps during World War II.

The public is invited to view the names and use a special Japanese hanko (a stamp or seal) to leave a mark for each person in the Ireichō as a way to honor those incarcerated during World War II. Community participation will “activate” it and rectify the historical record by correcting misspelled names or revealing names that may have been omitted from the record. The Ireichō will be on display at JANM through September 24, 2023. RSVPs are required. (*JANM Extends the Ireichō to December 1, 2024)

Visit janm.org/ireicho to learn more and to RSVP.

© 2022 Sharon Yamato