Read Part 1 >>

Perhaps the most important takeaway that we can apply to our own lives is how Gordon practiced what he preached. Combined with his Quaker membership and his early roots observing the honesty and integrity of his parents and other cooperative members, Gordon masterfully walked the fine line of not only being unapologetic for his beliefs, but also not being disrespectful of others who either did not share his beliefs or complied with the WWII orders and joined the draft anyway. Evidenced by so many non-Japanese Americans to whom Gordon was so dear, to his interactions with prisoners, and even government officials carrying out the orders that imprisoned him, it is quite extraordinary how, as a 24-year-old son of a poor immigrant farmer, he was able to conduct himself in such a dignified manner.

Even the most anti-Japanese officials had to respect how Gordon defied the mass removal order, by walking right into the FBI office instead of trying to be evasive, for example. Gordon’s legal advisor put it perfectly: “We’re not trying to hide anything or defy the authorities. It’s just that this is the way we feel.”

Remarkably, as mentioned previously, Gordon “maintained mutually respectful and friendly contacts with most of the prison officials.” Similarly, Gordon was just as well regarded among his inmates. Two examples are where Gordon was elected the new representative to the jail officials, handling the inmates’ requests and grievances; and where after a night of Gordon’s severely upset stomach echoing throughout the close quarters of the jail, several inmates asked in sincerity if he was okay and if there was anything they could do for him.

A chapter in the book titled, “Prison Meditations,” delves into Gordon’s thoughts on various topics. From there, the next few chapters detail Gordon’s thoughts regarding his legal case. Again, these chapters provide us for the first time with insights into Gordon the person as he was experiencing these events.

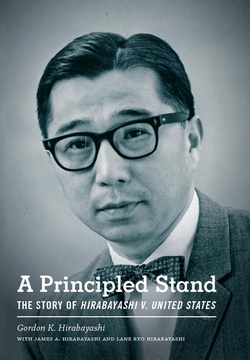

After reading these chapters, one cannot help but gain a deeper appreciation for the title of this book, A Principled Stand. On one level, yes, by defying the curfew and mass removal orders, Gordon stood up for his principles. On a deeper level, however, the more significant “principled stand” may very well have been after Gordon lost his legal case. Gordon writes that he “fully expected that the Constitution would protect me, as a citizen.” Incredibly, despite failed expectations, he did not abandon his beliefs and values. Gordon remained true to his belief that there was “nothing wrong with the Constitution. If it appeared good in the past, it is still potentially good. If the promised protection did not materialize, it is because those entrusted to uphold it have failed to uphold it.”

Of those whom Gordon referred as having failed to uphold the Constitution was the US Supreme Court. He had some important thoughts on the matter:

“[T]he Supreme Court seemingly abdicated its duty to defend and uphold the Constitution, deferring to the executive branch, saying, ‘You’re the specialists running the war, and who are we to tell you what to do?’ or something to that effect. Even with information classified in many respects, the justices could have sought particulars before abandoning the Constitution. Why in Hawai’i was it considered militarily feasible to investigate on an individual basis regarding national security, whereas it was ‘military necessity’ to uproot the entire Japanese American population on the West Coast on the basis of ancestry? Particularly when you count the fact that Hawai’i had already been subject to a devastating air attack, while the West Coast had not, and the Japanese American population in Hawai’i, more than one-third of the territory’s total, was more than double the number on the West Coast. The Supreme Court neglected to make this inquiry.”

Clearly, this book is an important contribution to Japanese American history. Beyond that, too, Gordon’s eventual vindication is a victory for all Americans. In Gordon’s own words: “[T]he fact that the courts vacated my convictions more than forty years after the fact is not only a victory for me personally, nor just for the Japanese Americans. It is a great victory for all Americans.”

One of Lane’s intentions with publishing this book was for “JA children to know about Gordon.” Lane expounded, “I hope they find in his life a basic lesson: that being of Japanese ancestry is a real asset, even if people may not like your ethnic background, and others may say that it is a disadvantage of some sort. Gordon did what he did precisely because he was exposed to elements of Japanese tradition and culture, but he was also very much a Nisei, and very much of an American, all at once. Concomitantly, I want children of all ages to know about Gordon’s principled stand, and to draw inspiration from his story.”

Another more nuanced intention for the book, according to Lane, was its relevance in a post-9/11 world. Lane elaborated, “We face many key decisions today in terms of protecting national security, but we need to avoid excesses. It was very much our hope that APS would be relevant to reflection on public policy options and decisions today. What we wanted was to make sure that people keep on thinking about our national security situation, as well as the different options that are available to protect ourselves today, deeply and carefully. And the Japanese American experience sheds profound historical light on such debates today.”

Relatedly, Lane is concerned that many Americans today know very little about what happened to the Japanese American citizenry during WWII. He said, “That’s why research, education, public forums, and events like ‘Day of Remembrance,’ pilgrimages, as well as the preservation of camps like Manzanar, Tule Lake, Minidoka, Heart Mountain, and the others, are so important.” Lane is encouraged, however, that so many college students are deeply involved in these educational efforts.

Ultimately, however, this book may not be about America’s past or future, or about providing insights into a Japanese American historical figure. It may speak to a dynamic much more basic.

At the heart of this work is a loving relationship between a father and son.

Looking back, Lane and Jim have had a long, working relationship that dates back to Lane’s doctoral training in Anthropology at UC Berkeley from 1974 to 1981. As a matter of fact, Lane has “just finished writing an essay that [he] hope[s] will be published in 2014 that details how deeply Jim influenced [him] in terms of [his] work in both Anthropology as well as in Japanese American Studies.” Furthermore, Lane added, “[S]ince maybe 1972, I’ve always had conversations with Jim about my paternal grandparents, the Hirabayashi family, about Gordon, and about Jim himself. So, in many ways, APS was the natural culmination of a 40-year conversation between a father and son about family matters.”

Lane described that his “father’s health was in decline during the period that he worked on APS, which was broadly between 2009 and 2012. He often dealt with pain—toward the end, persistent and debilitating back pain.” Lane did not “quite understand how Jim found the strength to work on the project so intensively.”

Publication of APS is made possible in part by grants from the Scott and Laurie Oki Endowed Fund, which publishes books in Asian American studies, and the Capell Family Endowed Book Fund, which supports the publication of books that deepen the understanding of social justice through historical, cultural, and environmental studies. The book also received generous support from the George and Sakaye Aratani Professorship in Japanese American Redress, Incarceration, and Community, at UCLA.

Upcoming Projects

Professionally, Lane is grateful to be the Aratani Endowed Chair at UCLA because it has provided him a tremendous opportunity to advance his research and writing on the Japanese American experience.

One of Lane’s upcoming projects has to do with putting together an anthology presenting the work and achievements of NCRR—once known as the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations, but now renamed as “Nikkei for Civil Rights and Reparations.” He worked closely with NCRR in Los Angeles between 1981 and 1983, so it has been a great privilege for Lane to work with their editorial team on this project. This project has deepened his understanding and respect for how much NCRR has accomplished since the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

Also, Lane is setting up a series of screenings of a wonderful documentary titled, “Issei: The First Generation,” by filmmaker Toshi Washizu. The filmmaker shot the footage in and around Walnut Grove in 1983 and his film revolves around Issei relating, in their own words, stories about their lives before, during, and after the war. On October 6, 2013, it will screen at the Buddhist Temple in Walnut Grove. On October 27, 2013, it will screen at the New People Cinema in San Francisco’s Japantown, in a program co-sponsored by the National Japanese American Historical Society. On January 26, 2014, it will screen at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo.

* * * * *

Please join us on Saturday, September 21, 2013, at 2 P.M., as the Japanese American National Museum hosts author Lane Ryo Hirabayashi for a book discussion regarding his and his father’s work, A Principled Stand: The Story of Hirabayashi v. United States. For more infomation >>

If you are unable to make this book event, it is available for purchase in the Museum Store or online at http://janmstore.com/151379.html.

© 2013 Japanese American National Museum