The Great Unknown: Japanese American Sketches is the first-ever anthology volume of author Greg Robinson’s Nichi Bei Times and Nichi Bei Weekly columns as well as other selections taken from outside periodicals.

Naturally, the majority of this anthology portrays individuals of Japanese ancestry: Issei feminist and peace activist Ayako Ishigaki, author Kathleen Tamagawa, pacifist militant Yoné Stafford, journalist and poet Eddie Shimano, writer and educator John Maki, journalists Buddy Uno and Bill Hosokawa, attorney Masuji Miyakawa, NFL player Arthur Matsu, poet and photographer Jun Fujita, cartoonist Robert Kuwahara, artist and author Miné Okubo, sculptor Shinkichi Tajiri, gay rights activist Kiyoshi Kuromiya, and dozens more. What is so striking is the sheer spectrum of topics depicted through these lesser-known and unknown historical figures: Issei women, literature and journalism, activism, civil rights, sports, arts, and homosexuality among others.

This anthology’s relative lack of focus on wartime confinement sets it apart from other Japanese American works. Sure, many of the entries touch upon an individual’s association with the WWII camps, but the author makes it clear that he is exploring—and wants his readers to comprehend—a much broader understanding of how Japanese Americans have impacted American history.

The author focuses attention “on the unusual and often rebellious sorts of characters who deviated from community norms,” thereby challenging “one-dimensional model-minority stereotypes of ethnic Japanese as conformist or colorless and reveals the complex and wide-ranging nature” of the Nikkei experience. Additionally, he goes “against the West Coast-centric focus of standard works by devoting attention to Nikkei throughout the country—notably the cosmopolitan communities of New York and Chicago.”

Like many reading this article, I consider myself somewhat well-versed in Japanese American history, but I am embarrassed to write that I learned about many of these Japanese Americans for the first time in this collection. Frankly, it was quite refreshing as well as enlightening to read about so many important Japanese American historical figures outside the strict (yet unimaginably courageous, of course) context of those who lived through the deplorable WWII incarceration. Everybody who picks up a copy of this book will soon come to view this work not only as an essential part of any home library of Japanese American literature, but also of American history in general.

As highly as I regard the Japanese American biographies in this anthology, though, the inclusion of so many non-Japanese Americans supporting the Nikkei community—most notably Caucasians and African Americans—takes this anthology to another level, both in historical significance and in entertainment value.

It is true that there have been others who have discussed non-Japanese allies, such as Shizue Seigel’s In Good Conscience book, John Esaki’s Stand Up for Justice short film, and a documentary that I previously reviewed for this website, the late Claire Mix’s Emmy-nominated Gila River and Mama.

The Great Unknown, however, separates itself from even these kindred works because of:

- the rare combination of insights into known figures such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Alan Cranston, mixed with

- substantial exposure to the lesser-explored historical relationship between Japanese Americans and African Americans.

To the first point, most people are probably familiar with Eleanor Roosevelt’s support for equal rights for African Americans (but not much in the way of support for Issei and Japanese Americans during WWII), Senator Alan Cranston’s role in the Japanese American redress movement, and Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy’s role in the issuance of Executive Order 9066. If that is all that one knows about these individuals and the historical events to which they are forever linked, I strongly urge people to read this anthology.

Reading what the author wrote about Eleanor Roosevelt was so eye-opening that I feel compelled to single her out and share some of what I have learned. I am probably in the majority in thinking that she did not do much to oppose the forced removal of Japanese Americans during WWII, but I was gladly wrong. Her hands were tied; but short of publicly opposing her husband’s policy, she was very busy voicing her displeasure through her actions.

The First Lady held press conferences and participated in national radio broadcasts in support of Issei and Japanese Americans; was instrumental in the easing of Treasury Department orders freezing “enemy alien” bank accounts; posed for photographs with Nisei representatives that appeared on the front page of West Coast newspapers; intervened to aid Japanese Americans threatened with dismissal from government jobs; corresponded with individual Nisei; spoke as frankly as she could in an interview by the Los Angeles Times newspaper about her visit to the Gila River concentration camp; supported the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council’s efforts to place Nisei students in colleges; supported Japanese Americans in her syndicated daily newspaper columns; and many other overt acts that are detailed in the anthology. Simply amazing.

To the latter point, the author spends substantial effort on “the disproportionate support offered by African American writers and activists, such as Paul Robeson, Erna P. Harris, Layle Lane, Loren Miller, and of course Hugh Macbeth for the rights of Japanese Americans,” not to mention Congressman Mervyn M. Dymally, an unsung hero of the redress movement. As the author notes, “there is a popular misconception that blacks and Asians are and have always been adversaries, and this is not only untrue but noxious if it stands in the way of current-day alliances.”

Before reading this anthology, apparently I was rather ignorant of the historical support of prominent African Americans on behalf of Japanese Americans. I am grateful to the author for expanding my knowledge and I hope other readers take advantage of the opportunity to do the same. The Great Unknown is worth grabbing even if one only has time to read, digest, and ponder the African American biographies contained therein.

With dozens of biographies comprising this anthology, my mind logically wonders about the immense amount of time and effort the author must have invested in its research over the years. I am always curious about an author’s or filmmaker’s research process.

The author Greg Robinson uses the classic tools of any historian (personal interviews, archival research, microfilm reading, online databases, genealogical databases, oral history databases) but to illustrate, he is kind enough to walk through a couple of examples taken from the biographies included in the anthology:

“In the case of Ayako Ishigaki, for example, I found a copy of the original edition of her book in the $1 book section of a used bookstore in NYC in 1997 or 1998, and was enthralled. I started looking for information on her. I wrote to a biographer of Agnes Smedley, who had interviewed her, I saw a poster for a speech of hers at the Old South Church in Boston, and I wrote to the museum she founded in Japan for her husband’s artworks. The museum people sent me info and a video of Ayako. I also found her Japanese language diaries and books on Interlibrary loan. Eventually I invited my friend Yi Chun Tricia Lin to collaborate with me on a new edition of Ishigaki’s memoir. Tricia’s Taiwanese father read Japanese from colonial days and helped us. I also had help from some Japanese-speaking friends who made summary translations. When I was living in DC I went through files of the Office of War Information, for which she had worked, and found intelligence reports her bosses kept on her.

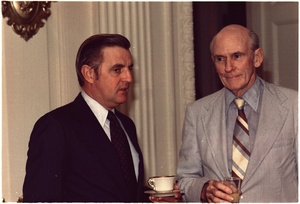

“In the case of Alan Cranston, I saw in Leslie Hatayama’s book about redress that Cranston had supported redress in part because of his personal history of meeting with Eleanor Roosevelt in 1942 to try and give her arguments to dissuade FDR from EO 9066. I wrote Cranston, and we began a correspondence. I met up with him near his home and did an informal interview. He put me in touch with a few people he had worked with at the Office of War Information, and allowed me access to his restricted papers at Bancroft Library. I also found material on Cranston in the OWI papers and in the Isamu Noguchi papers when I consulted them in NYC. Sadly, Cranston died before I could finish my first book, By Order of the President—I would have loved to have had an introduction or a blurb from him.”

© 2017 Edward Yoshida