On the Friday before Remembrance Day last year, I took part in a memorable presentation called Women and War, organized by the Meaford Community Theatre in the picturesque town of Meaford, Ontario. The first half of the program featured the recollections of Mrs. May Brown of Vancouver, who is now 93 years old and had lived in the Strawberry Hill farming community of the Fraser Valley during WWII. After the video of Mrs. Brown’s reminiscences was shown, I talked about and read from my book Torn Apart.

I was very moved by Mrs. Brown’s detailed account of those long-ago times—and in particular, her family’s relationship with their Japanese Canadian friends and neighbours, and the portrayal of her remarkable mother, Amelia Adams. Mrs. Brown was the first hakujin I have ever met to unequivocally state that what our community experienced after Pearl Harbor was racial prejudice. Here is an edited version of a transcript of Mrs. Brown’s interview.

The following is an edited transcript of material that formed the basis of a 2012 interview with Mrs. Brown, conducted by Janet Fraser. May Brown is a retired University of British Columbia coach and teacher, City of Vancouver Councillor, and member of the Order of Canada (1986) and Order of British Columbia (1993).

* * *

In 1927 our family moved from Alberta to the west coast of British Columbia. My parents bought a small chicken farm in Surrey in the Fraser Valley. The community where we lived was called Strawberry Hill as many farms grew strawberries, raspberries, and gooseberries there. Japanese families owned many of the farms and our neighbours were Japanese. The Entas lived to the north and the Ohori and Onashi families to the south.

Our family had five school-age children and we grew up with the six children of the Enta family. We went to school together, played together, and as teenagers went to dances and became good friends. The children of the Enta and other families were born in Canada and spoke English. However, the parents did not speak much English, especially the women who did not work outside their homes, where they spoke only Japanese.

Like many others, our family became victims of the Depression and my mother, Amelia Adams, had to raise her children by herself. We were able to grow much of our food but it was difficult to sell eggs for much money, so my mother took on an unusual job. She sold dynamite for the Farmer’s Institute, which gave her a steady income. My brother John quit school in Grade 8 to help provide for our family and we all picked berries at 15 cents an hour to buy our own clothes and school supplies.

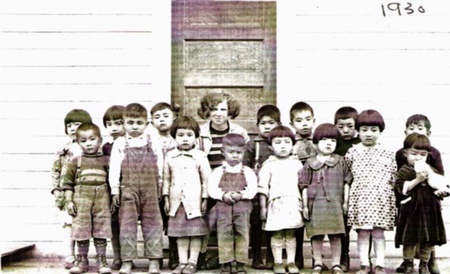

Milly, my oldest sister, was the first Grade 8 student to graduate from our two-room school. Until then, no one had been able to pass the government exams. When she was in high school, the Japanese community asked her to teach English to their young children to prepare the youngsters for school, so Milly had a Saturday job teaching twelve to fifteen pre-schoolers.

Milly Adams (later Milly Johnson) with her class of students at the JC Community Centre in Strawberry Hill, dated 1930.

In 1939 the war in Europe began. Young men were signing up, including my brother John. This was still the Depression, so for many of them the army provided a job. John joined a tank division, the New Brunswick Hussars, and trained at the Meaford Tank Range in Ontario before being shipped out to England and then southern Italy.

I finished high school and in 1940 started my first teaching job in Surrey. I was teaching Grades 2 and 3, and fifty percent of my students came from Japanese families. The Japanese were farmers (as well as fishermen) and would be out working by 7 a.m., so many of their children were sent off to school early. I got a ride part way to the school and walked the last mile. I opened up the school about 7:30 a.m. and would find jobs for the children. They loved to help—the girls would clean the boards and the boys would carry in firewood. One boy would open the top of the pot-bellied stove and another would throw in the block of wood.

Because it was wartime, we had regular air raid drills at school. When the siren sounded we blackened the windows, and if it happened in the morning, everyone would crawl under the desks or run across the street and hide in the trees. If the drill was in the afternoon, we would tell the children to run home as quickly as they could. It was mostly Japanese children that lived close to the school because that is where the fields were. One afternoon following an air raid drill a man came into the school laughing, with a story he thought was terribly funny. He said, “I was walking down the road and two little Japanese boys were running as fast as they could up the road. I asked, ‘What’s going on? Is something wrong?’ Without missing a beat they shouted out, ‘The Japs are coming!’” I thought it really showed they did not relate at all to the Japanese who were at war. They just knew they were supposed to run home and that’s what they did.

Many of my friends had teaching jobs in one-room schools in other parts of the province, which appealed to me. But my mother said that now that I earned a salary, I had to live at home for two years to support our family. My youngest sister Helen was working in Vancouver and on Sundays she and her fiancé would come home for supper. I clearly remember one particular Sunday—it was December 7, 1941. When Helen and Allan arrived, he announced, “The Japanese have bombed Pearl Harbor.” He was in the Navy reserves and he said, “I expect I will be called up soon.” Within a week he was, and began training before he was deployed.

My mother was an educated and capable woman and highly regarded in the Strawberry Hill community. The Japanese families often asked her to read and explain any official letters and government documents. One day our Japanese neighbour came to my mother with a letter they received and asked her to read it. The letter stated that the Japanese living on the coast were no longer allowed to have radios. The families in our area didn’t know what to do, so my mother said they could store their radios in one of our sheds until the war was over, which they did.

We began hearing terrible stories about the war in the Pacific. Japan captured Hong Kong, and British and Canadian soldiers were imprisoned and killed. Then Japan attacked Singapore. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States had finally entered the war. Fearing Japan might sight its sights on Australia, troops were being mustered on the west coast. People began to turn against Japanese-Canadians in British Columbia, seeing them as a threat. The government even believed that Japanese-Canadian fishermen were communicating with enemy Japanese ships, submarines, and airplanes out at sea, so their fishing boats were all confiscated. That’s also why the Japanese were not allowed to have radios, in case they tried to contact the enemy.

We had a different point of view. All the Japanese young people in Strawberry Hill were Canadian citizens, having been born here. Their parents were naturalized Canadians. But early in 1942, all Japanese-Canadians living on the west coast received a warning that they would be evacuated from their homes. No reason was given other than that we were at war. In June, my mother had to read the evacuation notice to our neighbours, and explain to them that a truck would be arriving in four days to take them away, and that they were allowed to bring one suitcase each.

I was teaching at Surrey High School near the end of the school term when the evacuation notices came. I recall all the teachers giving the Japanese students homework so they wouldn’t fall behind in their studies. It was so sad. The students didn’t want to leave, they didn’t know where they were being sent, they only knew they were being evacuated. They wept, the teachers wept, and then we hugged the students goodbye. Then they got on their buses and returned home for the last time. That was the last we ever saw of them.

On the Saturday morning after receiving their notices, our Japanese neighbours were in the fields early as usual, doing last minute weeding to leave their farms looking nice. Then they changed their clothes and were loaded into the back of open trucks with their single suitcase apiece and were taken away. They ended up at Hastings Park Exhibition grounds and were housed in the livestock buildings until they were shipped away from the coast. At that point, many families were split up with the women and children sent to internment camps in the interior and the men sent to work camps elsewhere. Some families were forced to leave the province and ended up working on sugar beet farms in Alberta.

They lost their homes, their possessions, their fishing boats, their businesses, their automobiles, and their farms. It is ironic, but many of these farms were leased to conscientious objectors, men who refused to sign up for military service. They were not farmers and did not look after the farms properly. They just took the crops and a couple of years later when the government decided to sell the farms, some tenants took everything they could—even door knobs off the doors and family furniture stowed in the attics.

The general public supported the actions of the government, even though some people questioned what was happening. Our family, especially my mother, was very sympathetic to the Japanese. To her, these people were Canadians, they were not foreigners. She felt terrible when they were leaving, as she stood at her kitchen window watching them being loaded onto the trucks. They were her friends and neighbours. She felt very badly that they were being treated this way because she believed they were good people and good citizens. It broke her heart because she felt they hadn’t had a chance to tell their side of the story.

It was difficult for our family to speak out because most people didn’t really know the Japanese-Canadians. I soon realized that it was best not to say too much because some people had family or friends fighting in the Pacific and we were hearing about the atrocities committed by the Japanese in the prisoner-of-war camps. But I still felt we were treating Japanese-Canadians differently than other groups in B.C. In Europe, we were fighting Germany and Italy. I’m sure there were many people of German or Italian heritage who were living here in our community but they were not evacuated. As soon as we were at war with Japan, and we could identify Japanese-Canadians, we began to treat the local Japanese as if they were the enemy, when in fact they were Canadian citizens of Japanese descent.

No wonder they were perplexed by what was happening to them. They were Canadians. The young people my age and the age of my siblings were born here, this was their country. They didn’t think of themselves as coming from Japan. Their parents had come from Japan, but our parents had come from Great Britain, so it wasn’t that different. But since you could identify the Japanese by their looks, we treated them differently.

Before the war in the Pacific, this sense of racism did not exist because there were so many Japanese in our community. In those years, half the population of North Delta, Strawberry Hill, South Westminster, and Kennedy was Japanese, and this was also reflected in the schools. The Japanese families worked extremely hard to make a living. They felt they were doing well because they owned their own land or fishing boats. They did not have a high standard of living, but neither did we. As teenagers in high school, we all felt equal. We didn’t feel any prejudice towards the Japanese living among us—they were our friends.

After the Allied victory in Europe in May of 1945, troops were being sent to the Pacific where the war still raged. That summer I was working at a YWCA camp in Quebec. One day the caretaker arrived with the mail and groceries. He said, “Some [radio] stations are saying [the United States] dropped a bomb on Japan. They claim if they drop another on Japan it may be so serious that the war will be over.” The Japanese surrendered on August 15, 1945.

One thing I will always remember—years later a reunion of many of the Japanese families from Strawberry Hill took place. My oldest sister Milly and her husband Frank Johnson were the only Caucasians invited. One of the boys who had lived next to us and knew Milly well said to her, “Milly, do you mind if I ask you a question?” She said she didn’t mind, thinking he was going to ask her something about the Strawberry Hill area. Instead he said, “Why did you let them do it to us?” Milly felt so awful. She just replied, “We didn’t think they should, but we had no way to fight the government. We were just little people—we didn’t know how to stop them.”

© 2013 Susan Aihoshi