I’ve been asked to talk about the history of Seattle’s Japanese American community. And because Densho has 750 oral history interviews and thousands of historic photographs, I thought it would be easy to pick out a few stories to share with you today. But the more I thought about the task, the more overwhelmed I became over the many choices.

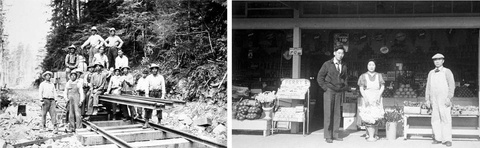

For example, I could talk about the Issei pioneers who came to Seattle in the 1880s and who worked in the lumber mills, salmon canneries, and railroads.

Or I could talk about how Japanese farmers dominated truck farming and the Pike Place farmer’s market in the early 1900s.

Or I could discuss the emerging Nisei generation in Seattle before the war with people like the writer and journalist Bill Hosokawa.

Or I could talk about the Japanese American community of Bainbridge Island, the first community to be removed and incarcerated by the U.S. government after Executive Order 9066 was issued.

Or I could talk about a story very personal to many families in Seattle, the sacrifices of men who fought in the war, and the suffering it caused families.

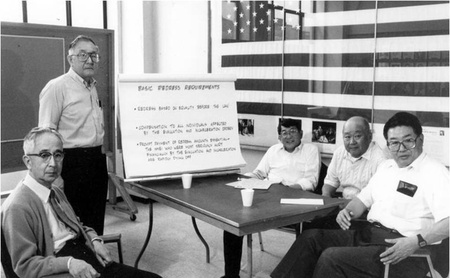

Or because this is the 25th anniversary of the passing of the Redress Bill, I could talk about the Seattle Redress effort and the first Day of Remembrance that was held in Seattle.

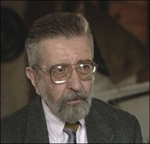

With all of these options swirling in my head, I decided to ask for help from someone smarter than I am. About a month ago I had lunch with Professor Roger Daniels, arguably the most important and influential scholar on the Japanese American incarceration.

Roger is a historian so he would have a long-term view, and he has worked with Japanese Americans across the country so he would have geographic perspective. And lucky for me, Roger lives in Bellevue which is a 20-minute drive from here.

At lunch, to try to get to the essence of the Seattle story, I asked Roger, “How are Seattle Japanese Americans different from other Japanese Americans?”

Roger thought for a few seconds and then said, “Seattle Japanese Americans have innovative ideas and they want other Japanese Americans to adopt these ideas.”

As Roger is telling me this, I’m nodding my head thinking perhaps I could title my presentation “Innovative Ideas from Seattle” and talk about James Sakamoto, the blind publisher of the Japanese-American Courier who started the Seattle Progressive League, one of the precursors of the JACL, or Henry Miyatake and the Seattle Evacuation and Redress Committee and their early efforts to get redress going. I’m thinking I could even talk about Densho and our use of digital technology to share the Japanese American story. There are so many innovative ideas from the Seattle Japanese American community.

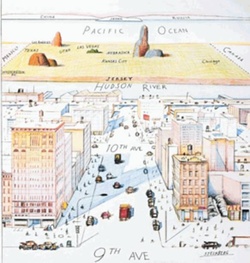

Roger could see that I was pleased with his answer, and just when I was going to compliment him about his wonderful insight, he raises his hand to stop me, and says, “Of course, Japanese Americans in Los Angeles don’t care about the ideas from Seattle, because to Los Angeles Japanese Americans, nothing matters outside of Los Angeles.”

Roger’s answer reminded me of this image of North America drawn from a New Yorker’s perspective.

So after thinking about it more, I backed away from the Innovative Ideas talk, and instead will focus on the theme of the conference—Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity—by talking about the story of Gordon Hirabayashi and why after doing hundreds of oral histories, his story inspires me the most.

Gordon was born in Seattle in 1918 and was raised in Thomas, a farming community 20 minutes to the south of Seattle. Growing up, Gordon was an excellent student, active with the Boy Scouts and the YMCA. When World War II started, Gordon was a Sociology undergraduate at the University of Washington. Shortly after the war started, there was a curfew order on the West Coast for anyone of Japanese ancestry. It was at this point Gordon did something extraordinary.

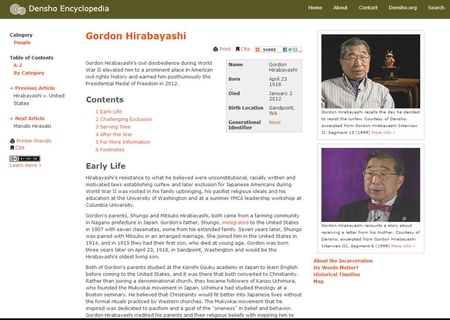

I interviewed Gordon 14 years ago and I am going to use a clip from that interview to have Gordon describe what he did. To get to the clip I am going to the Densho Encyclopedia.

For those of you not familiar with the encyclopedia, it is a free online resource about the WWII Japanese American experience. It currently has close to 400 articles, and by this time next year, there will be over 1,000 articles. This is a project supported by the Japanese American Confinement Sites Program of the National Park Service.

At a conference like this, I use the Densho encyclopedia from my smartphone to look up information during the sessions. For example, if I want to know more about the coram nobis cases, or the Redress Movement, or about the Tule Lake Segregation Camp, I can easily get the information on my phone. If you want more information on how to do this, you can ask at the Densho table right outside this room.

Here we are at the Gordon Hirabayashi article in the encyclopedia.

On the right-hand side of the article are a couple of links to videoclips. In the first videoclip I am going to show you, Gordon describes an epiphany he had about the curfew and then later about the exclusion orders. Gordon talks about being in the university library studying with friends and it is 5 minutes to the 8 p.m. curfew.

Watch videoclip of Gordon talking about the curfew >>

After Japanese Americans were removed to temporary detention facilities called “assembly centers,” Gordon turned himself into the FBI, defying the exclusion orders. Gordon also wrote a 2-page statement explaining why he was defying the US Government.

“I consider it my duty to maintain the democratic standards for which this nation lives. Therefore, I must refuse this order for evacuation.

From Gordon’s written statement

WHY I REFUSE TO REGISTER FOR EVACUATION

During the removal of Japanese Americans, Gordon is the only one to openly defy and turn himself into the authorities. And as can be seen by his statement, he did so based on the ideals of our country.

Gordon was placed in the King County Jail, which is about a 10-minute walk from here. Gordon was locked up in this jail for 5 months while he waited for his trial. While he was in jail, he received a letter from his mother who was incarcerated at Tule Lake concentration camp. This letter was very important to Gordon because the last time he saw his mother, she tearfully pled with Gordon not to go against the government.

Watch videoclip of Gordon talking about the letter >>

Gordon experienced physical hardships by being in jail for 5 months, but you can also see he suffered emotional hardships, especially feelings of guilt. However, Gordon did not give up. On top of these physical and emotional hardships, Gordon knows he will lose his case, as demonstrated by a letter he wrote to a friend.

I do not blame the court for that which I expect. The court seeks to perform its patriotic duty. Realism points to two important elements—race prejudice and war hysteria. Yet my idealism does not permit me to surrender. I am somewhat aware of what was and is; I have a glimpse of what ought to be. I seek to live as though the ought to be, is.

These are powerful words from a 23-year-old man sitting in jail.

Using the Bill of Rights as his defense, Gordon lost his battles in court, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1943. One of the ironies of Gordon’s conviction is that the government didn’t have the funds to ship Gordon to a federal work camp to serve his sentence, so Gordon ended up hitchhiking from Washington State to Arizona to serve his time. And then when he arrived at the work just outside of Tucson, he had to convince the clerk that he was a prisoner.

Eventually, 44 years later, in 1987, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals finally gave Gordon his justice by vacating Gordon’s conviction. You will hear more about this tomorrow morning from Judge Mary Schroeder who wrote the opinion for this ruling.

Gordon died last year at 93 years of age. In May he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Honor by President Obama, the highest civilian honor awarded.

For more information about Gordon’s life, especially through the voice of Gordon, I recommend the book A Principled Stand, which just came out and is written by Gordon’s brother, Jim Hirabayashi, who also died last year, and Jim’s son, UCLA professor Lane Hirabayashi, who is attending this conference.

In closing, I want to thank the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) for letting me share Gordon’s story. Keeping the Japanese American incarceration story alive is a passion for me. Not only am I interested in preserving these precious stories, I believe these stories, if kept alive and understood, will advance our democracy and prevent similar mistakes, like the incarceration of 120,000 innocent Japanese Americans, from happening again.

But keeping the story alive is not the responsibility of a few professors, or some high school social studies teachers, or organizations like JANM or Densho. It is a responsibility for all of us in this room. A benefit of this conference is that we are together to talk and learn from each other over the next two days. Listen to what others say. Participate in the discussions. Reach out to new friends. And most importantly, when you return home, please share what you heard and saw. And together, we will keep the story alive.

(All photos are the courtesy of Densho)

*Tom Ikeda was a presenter at the “Opening General Session with Keynote Addresses” during JANM’s National Conference, Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity in Seattle, Washington. The video of his speech will be available on Discover Nikkei soon!

© 2013 Tom Ikeda