It was near the closing of camp, when restrictions were being relaxed a bit, that I heard from our neighbor George about Mr. Crane, the Camp Reports Officer, taking a small group to entertain some high school students at Cedarville. Cedarville is in Modoc County, about 120 miles from Tule Lake.

George and a few of his musician friends were going and he asked me if I would be interested in joining them. My first thought was “I don’t sing or play an instrument, what could I do?” George said they wanted someone to provide some comic relief and he thought that maybe I could tell stories. Stories? What stories? Certainly not about, not camp to white high school kids who probably never saw any Japanese in their life before, living in a small town in Northern California, probably very conservative.

It was around November 1945, not long after the end of the war. We were hearing of the “No Japs” signs up in our hometown, and of dynamiting of barns, even the burning down of the home of a 442nd veteran. But the chance to go outside was terribly appealing. I would do anything for that; even make a fool of myself if I had to. After being cooped up for almost four years, the thought of being free again was overpowering. I had to go. I told George sure, I was more than willing to go, and I’d find something to do to make my going purposeful.

I quickly looked though some magazines that were in the block office in search of jokes. I found a few that struck me as being funny without being off color, some with even a bit of wit. I memorized them, so that they were a part of me, before joining the group early one morning.

The car was loaded down with Mr. Crane, who drove, and the five of us plus various musical instruments. I believe there was a violin, a saxophone, an ukulele, and an electric guitar.

First we stopped in the town of Tulelake; I think Mr. Crane stopped for us so we could experience being out of camp. So this was how it felt to be free. It was indescribable; we couldn’t help rushing around. We didn’t care if we attracted strange looks from the townspeople; and in fact we probably did, but we were too busy to notice, running in and out of the stores. At one store, which I believe was a drug store, I made a big purchase of a pack of Wrigley spearmint gum. What a thrill that was.

Back in the car we continued on our trip. Though crowded, it was great to be riding in a car, a passenger car, going miles and miles away from camp. We went through Alturas, the county seat of Modoc County, and finally arrived at Cedarville, which was at the foot of a mountain close to the California/Nevada border. It was around 11 o’clock.

The students were all seated in the classroom, awaiting our arrival. They seemed curious to see us, but were warm and welcoming. I’m sure they had been well briefed about us—that it was an accident of war that we were confined in the camp at Tule Lake, that we were just as American as they were.

I noticed that some of the students were sitting together as if on a movie date, the boys with their arms around their girlfriends. After a few words of welcome by the principal, the program began, and the musicians played several numbers.

Recently, I asked Ed, who played the ukulele, what he remembered of the trip. After more than 50 years, he remembered some things I didn’t and I remembered some things he didn’t. He thought they played some Hawaiian songs. I remembered a violin solo, but he wasn’t sure of that.

The audience was very enthusiastic; they acted like they had never heard live music before. Maybe they hadn’t. Then I was introduced. I was the only one speaking directly to them. I said that since I couldn’t sing or play an instrument, I would tell some jokes and I heard a murmur go around the room.

Even as I was telling the first joke, I wondered how it would go over. I believe the jokes had to do with little Audrey—rather silly jokes, I’d be embarrassed to tell them now. But much to my surprise and delight, the audience roared from the very first joke which energized me to tell all the jokes that I had prepared and I had them literally rolling in the aisles. Were the jokes that good? Was I that much of a comedian? Who knows? But it was exhilarating and memorable.

After the program was over, the kids gathered around us to tell us how much they had enjoyed it. I think they wanted to get a closer look at us, make sure they were actually seeing what they were seeing. Some even offered to give us a tour of their school.

Then we were taken through the town to a little restaurant where the local Lions Club had their weekly meeting. Here, we were served lunch with the club members, most of whom were fathers of the kids at the high school we had just visited.

I don’t remember what we had to eat; nothing remarkable, though it was cattle country. At any rate, they had heard of the great impression we had made at the high school so they were all very warm and friendly.

After lunch we repeated our program. Again I went through my joke routine for the club members, some of whom looked a little lost without their horses. Most were cattle ranchers but there were some storekeepers and a few professionals. I swear they laughed at my jokes even louder than the kids had earlier. I could tell the men were having a rip-roaring time, slapping their thighs; I’m sure they had had something to drink by then. But how they could laugh.

When we returned to camp, it was already past suppertime in the mess halls. Mr. Crane invited us to have dinner at his place. He had bought some steaks in Cedarville and now Mrs. Crane prepared them for us with lots of potatoes smothered in onions. “What a treat this is!” we all exclaimed. “You earned it,” Mr. Crane said, pleased with us for having done a good public relations job. The steak dinner, our first in over three years—what a fitting ending it was to a trip that we would remember for the rest of our lives.

*This article was originally published in Swimming in the American, a Memoir and Selected Writings, San Mateo, CA, Asian American Curriculum Project, 2005.

* * *

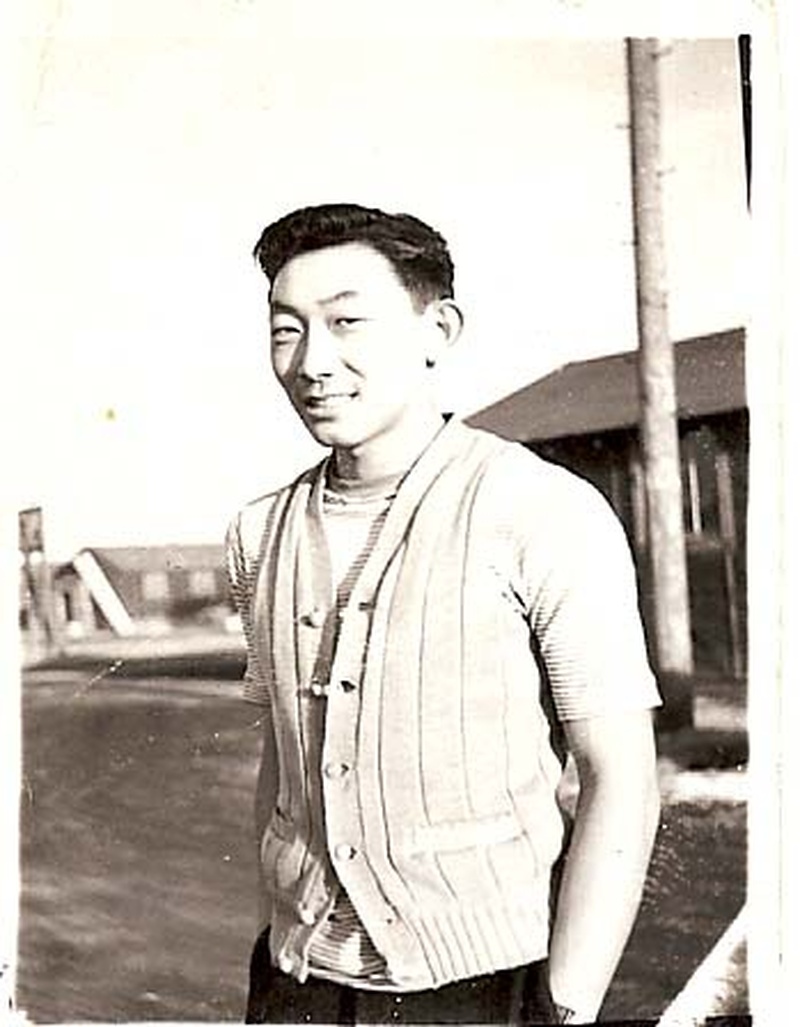

* Hiroshi Kashiwagi will be speaking at "The Tule Lake Segregation Center: Its History and Significance" session at JANM’s National Conference, Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity on July 4-7, 2013 in Seattle, Washington. For more information about the conference, including how to register, visit janm.org/conference2013.

© 2005 Hiroshi Kashiwagi