The next four years were a blur. I should have suspected that something was wrong with Dad when he abruptly stopped volunteering at our neighborhood church, the Kotohira Jinsha. He told me that he just wanted to take a break from helping out, but one day when I was shopping at Marukai, I ran into Mrs. Watanabe, a long-time friend of my father’s who also was a member of that church. She asked how Dad was doing, and the deep concern in her eyes unsettled me. As we continued talking, I became increasingly dismayed thinking about my father’s mental health. She told me that at first he was having trouble remembering people’s names, but then he’d completely forget about certain commitments he had made. “The last time I saw him,” Mrs. Watanabe recalled, “I could tell he didn’t recognize me and was embarrassed having to pretend to know me. But please tell him that we all get old and he shouldn’t be ashamed to come to church.”

Of course Mom and I had noticed that Dad’s memory had been slipping, but we had assumed it was all part of normal aging, not anything more pernicious. But after talking with Mrs. Watanabe, every odd thing that Dad had done, like leaving a screwdriver in the refrigerator, accrued such ominous import. An appointment with a neurologist confirmed our suspicions of Alzheimer’s, which in my father’s case progressed with frightening speed. Within a year he couldn’t be outdoors by himself, and within three years his body had forgotten even how to perform rudimentary actions, like swallowing food.

Now, almost a year after Dad’s passing, I was still worried about Mom, whether she would eventually rally from the loss of her long-time partner in life, or whether she would whither. She had yet to touch any of his clothes or other belongings in their bedroom, although I had offered a few times to help clear and donate his things to his church and Goodwill. More worrisome, she had let many of her friendships lapse and would leave the house only to shop for groceries.

So I was pleasantly surprised when she called one day to invite me out for dinner. Her voice was light and cheerful, something I hadn’t heard in a while, and I was elated at her choice of restaurant: Ideta, our neighborhood favorite for Japanese cuisine. Ideta was where our family had celebrated many important events—my acceptance into college, Dad’s retirement, my parents’ sending in their last mortgage payment.

After we were seated, Mom handed me a small, rectangular piece of thick paper, smiling in anticipation of my reaction. It was a check from the federal government made out to her for the sum of $20,000. I couldn’t believe my eyes. “What is this, your reparation?”

“Yes, finally,” she beamed.

I sat there in awed silence. Actually, I hadn’t really thought about her redress application for quite some time. After her appeal was denied, I had assumed it was a closed matter and had pushed thoughts of it well outside my mind, less I become aggravated about the painful injustice. “Did they just send you the check out of the blue?”

Mom reached for a piece of paper from her purse. It was a letter from the Department of Justice, stating that people had been reviewing an earlier interpretation of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Mom explained that, after she had appealed the initial rejection, she learned that she’d been declared ineligible because she had “relocated” to an enemy country (that is, Japan) during the war. She was incensed. “I did not just relocate,” her voice indignant. “I was deported.”

Before I could say anything, we were interrupted by our waitress, who described the daily specials, with each dish sounding more delectable than the previous. Mom went with her usual shrimp tempura and I ordered one of the specials: buri nitsuke, yellowtail fish simmered in shoyu, sake, and mirin. After the waitress left, I said, “I know the federal government isn’t known for its speed, but I’m still surprised it took four years for them to admit its error.”

“You don’t know the half of it!”

Over dinner, Mom recounted her long battle, a crusade that would turn on pivotal information from her past. After several unsuccessful legal maneuvers, Mom’s attorney figured out that he had been attacking the problem from the wrong direction. From his research on Mom and her family, he had learned about her earlier immigration difficulties, that she was initially denied her U.S. citizenship when she returned to Hawaii after the war.

He now seized on that information to make his case. He shrewdly argued that, when Mom was detained at Sand Island decades ago, the U.S. government had eventually admitted its error in denying her the right to her citizenship because, as was ruled at the time, she was just a minor when her family was shipped to Japan. So how could she now be held accountable for the decisions that her parents may, or may not, have made?

I stopped eating. “That’s amazing, the connection between the two cases.”

“There’s something more,” Mom added. She explained that, according to her attorney, the Department of Justice had recently ruled on key language in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988—text that had expressly ruled ineligible any person who had relocated to an enemy country during the war. The ruling was that the exclusion applied only to those individuals who had voluntarily relocated. This then exempted minors like my mother.

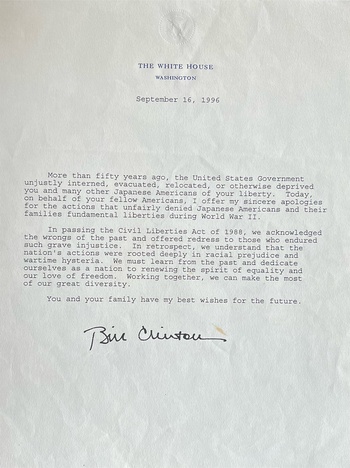

As I sat there, trying to absorb everything that Mom had just told me, she handed me a second letter, this one signed by President Bill Clinton. In it, the President apologized on behalf of the country for “the actions that unfairly denied Japanese Americans and their families fundamental liberties during World War II.”

Mom lowered her chopsticks onto her rice bowl, and looked straight into my eyes. “You don’t know how much that letter means to me, much more than the $20,000.”

“I can’t imagine.”

Then, her lips curling into a warm smile, she announced, “And this is what we’re gonna do with the $20,000. You and I are taking a trip to Japan, where you can finally meet your Uncle Yuki.”

“Wow, that would be awesome!”

“We’re going to have so much fun. I only wish Dad were still here to join us.”

We ate in silence for a few minutes, both of us deep in thought. Then, as Mom finished the last of her tempura, she said, “You know he would often call me ‘hard-headed.’”

“Well, you kinda are,” I smiled.

“It was a big problem when we first got married and we’d clash even over little things, whether we could afford a color TV, what color to paint the bedroom, which kind of fruit tree to plant, mango or lychee. Thankfully over the years I learned to control my stubbornness, but fighting for the reparation was different. I had to be hard-headed. I just did.”

I was suddenly overcome with such emotion. “Mom, I’m so proud of you, your courage to fight for what was right, your not giving up against the federal government.”

“What, me?” she chuckled, as she sipped her tea. “Come on, I’m just a simple housewife who didn’t even finish high school.”

Now it was my turn to laugh. “Yeah, right, as if…”

“Wait till you taste the food in Japan,” Mom interrupted me. “The dishes here are good, but you’re gonna love everything in Japan.”

Something told me that the food wasn’t the only thing I’d be enjoying about our upcoming trip. It would be the first time I’d be visiting the land of my ancestors and, for Mom, the trip would complete the journey she had long been on. She had once told me that she felt guilty that it had fallen on Uncle Yuki to care for Grandpa and Grandma in their elderly years before they passed. Mom had sent him money on several occasions to help with the costs incurred with that care, but now she could express her gratitude in person for all that her older brother had done.

After we had finished our dinner and the waitress had brought the check, Mom quickly seized it, her fast, nimble reflexes startling me. “This meal is on me,” she declared. “Or, actually, this meal is on the U.S. government, as it should be.” With that, she smiled, her face quickly softening, with years of bitterness melting into a moment of blissful triumph.

* * * * *

This short story was originally published in the Bamboo Ridge journal (Issue No. 124).

© 2024 Alden M. Hayashi