As part of my ongoing research on Congress and the incarceration of Japanese Americans, I have found several examples of pressure tactics used by Congress to influence the U.S. Army and the War Relocation Authority’s policies towards Japanese Americans. Perhaps the most famous examples are the House Un-American Activities Committee’s series of investigations into the WRA and Dillon Myer. In other cases, members of Congress proposed legislation to respond to the complaints of their constituents.

Regardless of whether the legislation could receive enough votes to become a law, members of Congress submitted proposals to gain media attention and respond to their constituent’s complaints. In one unique case, several American pottery unions in 1943 asked their representatives in Congress to pass a law banning Japanese Americans from producing pottery in the camps.

The story begins at Heart Mountain concentration camp, where master potter and art instructor Daniel Rhodes suggested to the WRA that the camp purchase a pottery kiln. An accomplished painter originally from Iowa, Rhodes was among the first graduates to receive a Masters of Fine Arts from the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University.

In 1942, after working with Glidden Pottery in New York, Rhodes joined the War Relocation Authority as a ceramics instructor, and the WRA sent Rhodes to Heart Mountain to teach ceramics. Rhodes convinced the WRA to purchase a surplus industrial kiln that previously belonged to the National Youth Administration, a New Deal program that trained young adults in industrial skills, from Solvay, New York.

The kiln, according to Rhodes, would help with teaching inmates how to produce pottery that would prepare them for employment outside of camp and supply the WRA with enough pottery for the ten camps. With 100 employees, the pottery plant could produce 6000 individual pieces of dishware per week.

On November 7, 1942, the Heart Mountain Sentinel reported that the camp planned to establish a pottery-making project based on Rhodes’s plan. The camp would acquire several kilns that would produce pottery for all WRA camps. Like other labor projects, such as the camouflage net factory at Manzanar and the model ship factory at Amache, the Heart Mountain ceramics project secured a contract with the U.S. Armed Forces for producing pottery, and anticipated peak-production to be reached within five months.

Yet the purchase of the kiln provoked a unique uproar from potters across the U.S. From the beginning, pottery companies protested the creation of the camp pottery factory. Even before the program was announced, The Heart Mountain Sentinel stated that WRA officials consulted with the National Brotherhood of Operative Potters in East Liverpool, Ohio. Considered the center of pottery production in the United States, East Liverpool, Ohio was the home to The National Brotherhood of Operative Potters and several major pottery and chinaware producers such as East Liverpool Pottery and The Hall China Company.

Nonetheless, several pottery groups called for the closure of the Heart Mountain kiln, claiming that allowing “Japanese” to learn how to make pottery using modern industrial techniques would undercut the “domestic” dishware market—even though Japanese Americans had no connections to Japan’s pottery industry nor that they were part of the domestic market as Americans.

When the story was first announced and representatives of Buffalo Pottery Inc. in New York complained to their representative, John C. Butler of New York, the War Relocation Authority reassured Butler that none of the pottery produced in camp would leave the barbed wire. On January 1, 1943, the Heart Mountain Sentinel announced the anticipated opening of another kiln. The new kiln, purchased from the Denver Fire Clay company in Colorado, was oil-fired and could reach temperatures of 2400 degrees Fahrenheit, and would expand the industrial capacity of the pottery factory.

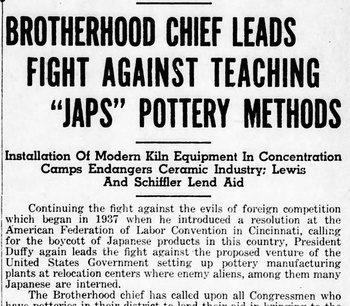

The announced expansion of the Heart Mountain kiln triggered a greater wave of xenophobic uproar from several pottery companies. The National Brotherhood of Operative Potters raised an uproar in their newsletter after learning that Japanese Americans in Heart Mountain produced pottery using a kiln purchased with government funds. The members informed Brotherhood President James Duffy, who took his supporter’s complaints to Representative Earl Lewis.

Lewis was sympathetic to the Brotherhood’s cause; as a politician, Lewis won the votes of the Brotherhood by promising to raise tariffs against imported Japanese pottery. In the 1936 congressional election for Ohio’s 18th District, Lewis appealed to East Liverpool voters by promising to cut the importation of Japanese ware pottery, which he claimed was made from workers paid “starvation wages.”1

In a letter dated February 1, Duffy wrote to Lewis that the manufacturing of pottery by Japanese Americans challenged the American Federation of Labor’s ongoing boycott against Japanese produced goods. Duffy also reminded Lewis that American potteries had suffered for several years in part due to “the cheap pottery that is manufactured in Japan.” Combining racist xenophobia with nativist consumerism, Duffy instructed Lewis to bring their issue to the War Department and government agencies responsible for dealing with Japanese Americans.

On February 9, 1943, Representative Lewis submitted to the House Military Affairs Committee a bill, House Resolution 79, that would direct the WRA to require all enemy aliens, “including persons of Japanese blood,” to cease manufacturing pottery.2 That same day, Lewis took to the House floor to speak in support of his resolution. In his speech, Lewis asserted that the War Relocation Authority’s plan to help Japanese Americans learn how to produce pottery threatened the jobs of white American workers after the war:

The War Relocation Authority is setting up modern potteries at H[e]art Mountain, Wyoming, and perhaps at other Japanese internment camps, in which it is proposed to teach Japanese to make pottery by American methods and American equipment, returning to Japan and adding their skill and knowledge of American methods to the already existing Japanese pottery industry and further adding to our troubles in the post-war period by the skills and training which they have acquired while prisoners in American internment camp. Mr. Speaker, I consider this policy of the War Relocation Authority the most stupid and ruinous activity imaginable.3

Lewis vowed to pressure the War Relocation Authority to stop the establishment of pottery kilns within the camps. (Interestingly, both Lewis and Duffy referred to the WRA centers as “concentration camps.”) Lewis’s presumption that incarcerated Japanese Americans planned to go to Japan after the war (“return” in his words, despite many not having visited Japan) underscored the xenophobic nature of his remarks.

Duffy also sent letters to Representative Andrew Schiffler of West Virginia, who forwarded his complaint to the War Department. Schiffler’s district also contained several national pottery companies, including the Homer Laughlin China Company that produced the famous Fiesta line of dinnerware.

In response to Schiffler’s letter, Secretary of War Henry Stimson informed Schiffler that the production of pottery was allowed as part of the camp’s manufacturing program for producing dishware for camp inmates. Stimson told Schiffler that he found the WRA’s operation to be “sensible.”4

Despite Stimson’s endorsement of the WRA’s project, though, administrators cancelled the proposed kiln at Heart Mountain. On March 13, the Heart Mountain Sentinel reported that WRA officials had cancelled the pottery factory “due to change in policy of WRA regarding relocation.” Although the WRA did not disclose a specific reason to residents why the sudden change in policy, the pressure campaign by Lewis and Schiffler must have had some calculated effect on the organization’s decision.

A week later on March 19, 1943, Ohio papers reported that Lewis received word from the WRA that the kiln project had been abandoned.5 A few weeks later, on April 1, Representative Earl Lewis declared himself victorious when he informed members of the National Brotherhood of Operative Potters that the War Relocation Authority had decided to sell off the remaining kiln equipment from Heart Mountain.6

The closure of the Heart Mountain kiln may have stopped inmates from producing pottery for the camp community, but it did not end the dreams of some aspiring Japanese American potters. Perhaps the best example was Minnie Negoro, a Heart Mountain inmate who became a successful pottery artist after the war.

Born in Montebello, California, on April 27, 1919, Negoro studied art at Pasadena City College and University of California Los Angeles. When the Army ordered Negoro and her family to Santa Anita detention center, she found work as an art instructor and illustrator for the Santa Anita Pacemaker.

In December 1995, Negoro told a reporter with the The New London Day (now known as The Day) about her experiences in camp: “It was a frightening place, with guard towers and MPs who were told to shoot anyone going outside or over the gate. It was a concentration camp. I just wanted to get the heck out of there and to get as far away from the West Coast as possible.”7

When the Army transferred Negoro to Heart Mountain in fall 1942, she quickly became a student of Daniel Rhodes. At Heart Mountain, Minnie Negoro showed potential under Rhodes’s tutelage, and was photographed by the WRA working at the potter’s wheel as an example of the industrious success of some camp inmates. She recalled going on several trips with Rhodes to find clay in the land surrounding Heart Mountain.

Although the factory failed, Rhodes mentored Negoro, and he eventually recommended her to enroll in Alfred University. Negoro left camp to matriculate at Alfred University in 1944. In 1947, Negoro received the Richard Gump award at the 12th National Ceramic Exhibition for a tea set she designed. The award, named after a wealthy San Francisco importer, selected winners whose pottery were best suited for mass production.

After completing her Master of Arts at Alfred University in 1950, Negoro moved to Westerly, Connecticut, where she opened a ceramics studio at Dunn’s Corners. In 1952, she moved to Mason’s Island, a small community located on an island at the mouth of the Mystic River. On the island, she built a small house where she kept several potters wheels, producing pottery for several decades.

From 1954 to 1965, she worked as a pottery instructor at the Rhode Island School of Design and at New York University. In 1965, she became a professor of ceramics at University of Connecticut, where she taught for twenty-four years until 1989.

Her designs of bowls, vases, cups, and glazes were widely celebrated, and were exhibited in several major cities around the world, and her pottery is housed in several museums including the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and Smithsonian Institution and Freer Gallery in Washington, D.C. Art critics often praised her glaze work and unique pottery style, and several of her pieces fetched prices in the thousands. She died on May 1, 1998.

Even though Congress ended the Heart Mountain kiln, it never stopped Minnie Negoro.

Notes:

1. “Vote to Protect Your Job! Earl R. Lewis, Republican Candidate for Congress.” The Evening News (East Liverpool), October 17, 1936.

2. House Joint Resolution 79, February 9, 1943. Record Group 210, Box 240, National Archives.

3. “Duffy Asks Protection for Potteries.” The Potter’s Herald, February 18, 1943.

4. “Duffy Asks Protection for Potteries.” The Potter’s Herald, February 18, 1943. The article reprinted the correspondence between Lewis, Schiffler, and Stimson.

5. “Pottery in Jap Camps Dropped; WRA Acts After NBOP Protest.” The Evening Review, March 19, 1943.

6. “Kiln, Equipment for Sale.” The Potters Herald, April 1, 1943.

7. Steven Slosberg, “Shaping a Life from Clay.” The Day, December 27, 1995.

Writer's note: University of Connecticut history professors Hana Maruyama and Jason Oliver Chang are putting together an exhibition on Negoro's career for the Benton Museum. If you have any additional information about Minnie Negoro or the Heart Mountain ceramics project, please contact them at hana.maruyama@uconn.edu

© 2024 Jonathan van Harmelen