Start by knowing

When the new coronavirus, which was first identified in Wuhan, China, also raged in the United States, President Trump and other senior members of his administration called it the "China virus." The virus became associated with China, and then with Asia. As a result, there were frequent incidents of attacks and discrimination against people of Chinese and other Asian descent in the United States.

Examples of this discrimination against Asians in the United States include the anti-Asian movement against Chinese immigrants and the wartime internment policy against Japanese Americans and Japanese people, as well as the attacks and discrimination against Asian Muslims after the 9/11 attacks in 2001.

Of course, discrimination in America is not limited to Asians. However, discrimination against ethnicities and races within Asia, such as Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and Indians, is also discrimination against the broader Asian group. For those who are discriminated against, it is not surprising that they naturally develop a sense of being an American who shares something in common with others, even as they are Japanese, Chinese, or Filipinos.

In other words, they are both minorities in American society, late-arriving immigrant groups, and groups far removed from the language, culture, and religion of white society. If they were to be given a name, or to name themselves, they would be Asian Americans.

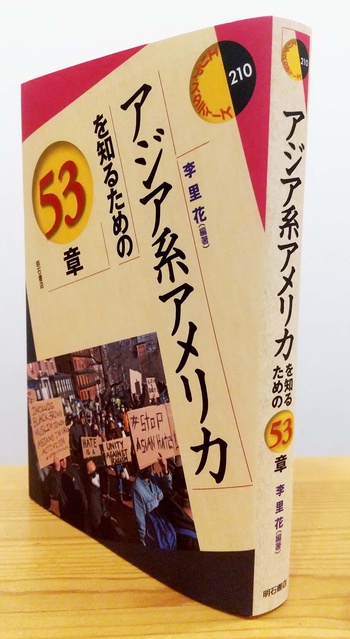

How should we understand "Asian America," a concept that encompasses a vast range of people and people with various ethnic and cultural backgrounds, like the least common multiple in mathematics? The recently published "53 Chapters to Understand Asian America" (edited and written by Li Rika, Akashi Shoten) answers this question from various angles.

The book is one in the company's "Area Studies" series, which explains the history and culture of various parts of the world. Divided into 53 themes, 41 researchers, including those specializing in American society and immigration, have shed light on "Asian America" from the perspective of their respective areas of expertise.

The editor and author, Lee Rika, is a professor at the Faculty of Policy Studies at Chuo University, and specializes in immigration research. She was born in Japan as a third-generation Korean resident of Japan to an American immigrant father and a Korean resident of Japan mother, and is familiar with both Japanese and Korean culture, but also lived in the United States as an immigrant for several years.

Also, from my experience as an international student in the United States, I became interested in ethnic towns for Asian Americans because they play a major role physically and spiritually for people of the same roots, and are places where histories and memories of hardship remain.

For this reason, he initially planned to write a book introducing Asian ethnic towns in America, and as a starting point, he searched for books on the theme of Asian America. However, he realized that there were few books that comprehensively covered the recent trends of various ethnic groups, which led him to plan this book.

Approximately 14 million people are from Asia

In this book, Asians are defined as "people with roots in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent," and as of 2023, there are approximately 14 million people of Asian descent living in the United States.

This book will analyze these 14 million people statistically by race group and place of residence, and then provide an explanation of individual ethnic groups in America, such as Japanese and Chinese.

Next, the book summarizes the hardships of being Asian, such as the history of Asian exclusion and the social struggles of being a minority, and the movements to overcome them. It also looks at Asian America from various fields, including politics, economics, education, music, theater, food, art, rap, religion, and graves.

Furthermore, the book examines some of the trends among Asian Americans not only within the United States but also across borders. For example, it examines the history of activism calling for solidarity with other Asian countries, as Asians, their roots, have been oppressed by American imperialism.

Lee emphasizes the significance of Asians being recognized above all else. In the past, people who immigrated to America from Asia were perceived as individual groups that bore the slogan "Chinese," "Japanese," "Indian," and other national or ethnic identities. They were also referred to as "Orientals," a kind of "foreigner."

Although they were treated as minorities in the same way, there was little solidarity between them. This changed during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, when Americans with Asian roots also asserted their rights as minorities, at the same time questioning their own identity and striving to establish it in society.

The term "Asian American" was born during this time. "The term 'Asian American' began to be used when Emma Gee and Yuji Ichioka, who were graduate students at the time, founded an organization called the Asian American Political Alliance." (From the introduction to this book). This trend led to the establishment of "ethnic studies" at American universities to study minorities.

Cultural activities with an awareness of "Asian America" also became more active, and in the world of theater, Frank Chin's "Chinaman in the Chicken Coop" (1972) was the first Asian play to be performed at a commercial theater in New York. In music, the activities of a group called HIROSHIMA, which is not introduced in this book, are unique. Formed in 1973 by third-generation Japanese Americans, it was what was considered a fusion band at the time, incorporating Japanese instruments such as the koto and taiko drums. They performed activities unique to a group located between Japan and America, such as singing "Thousand Cranes," a song for a girl who died in the atomic bombing.

In the world of literature, in the chapter "Asians and Literature," Rie Makino gives a chronological overview of Asian American literature, from Asian immigrant literature to the present day. In the book, she regards "No-No Boy" by John Okada, a second-generation Japanese-American and a pioneer of Japanese American literature, as "the embodiment of Asian America."

This novel was published in 1957, before the term "Asian America" was even coined, and it went largely unnoticed. In the 1970s, young Japanese and Chinese people born after the war discovered the novel and, declaring "this is our literature," published it themselves, leading to a reevaluation of the novel.

At a time when American literature typically means only white literature such as that of Hemingway or Faulkner, Frank Chin is delighted that thanks to John Okada, Asian Americans have a literature of their own, saying, "John Okada is the proof of our yellow soul."

It is a word that confirmed my Asian American identity through Okada. It is also a symbolic word that helps me understand "Asian America."

Now, about half a century has passed since the Asian American Awakening, and the older immigrant families are now in the 6th or 7th generation. The way of relating to roots and the sense of belonging are different even among the same Asians and the same ethnicity. People who immigrated from Japan to America after the war are called "New First Generation," and the concept of "immigrant" no longer applies.

In this situation, I would like to see further research into what the Asian American identity is, what its core is, whether it will spread, or whether it will fade.

© 2024 Ryusuke Kawai