Every time I look at Japan, something always surprises me, from the aesthetic shape of its geographic map, almost in the shape of a dragon, to the soft falls of snow on the slopes of Mount Fuji, contrasting with those beautiful tones of its skies and mountains. landscapes that occur with the changes of season.

This time I was fascinated to realize that tea drinking has become an art. The tea ceremony as an art is not recent. It came from China in the 12th century, but in Japan it began to develop around the 15th to 16th centuries. Murata Jukoo is known in history as the first to develop it as a spiritual practice. Sen no Rikyu , perfected the “way of tea,” is the most well-known and revered historical figure of the tea ceremony.

Following the teachings of his teacher Takeno Joo , he led to the complete development of the “way of tea” ( chad ō ), also perfecting many new forms in architecture, gardens and art. He taught “ ichi-go ichi-e ” (once, an encounter), which was taken from a book Ichieshu written by Li Naosuke, the wabi or aesthetics of serene elegance and simplicity, and the principles of harmony (和wa ), respect (敬kei ), purity (清sei ) and tranquility (寂jaku ) which remain the central pillars of the tea ceremony.

The tea ceremony, chanoyu (茶の湯) or sadō, also called chadō (茶道), is the ceremonial preparation and presentation of matcha powdered green tea. (抹茶). The way or art in how it is done is called (o)temae ([お]手前).

Many of us have attended and solemnly followed numerous tea ceremonies. We have taken the okashi (sweet) and the tea that they offer us silently, without knowing the reason why it is done this way: the sweet at the beginning tends to reduce the bitterness of the matcha. Very logical, right?

Many people ask me why learn Chanoyu. At the beginning I didn't know it well either, but now that I'm beginning to understand it better, I know why even after hundreds of years it persists and they continue to practice it.

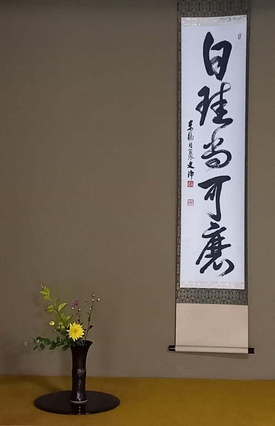

The first thing I learned is that, when heading to the tea house, you should slowly cross the beautiful garden that surrounds it, leaving your worries and regrets behind, entering with humility to participate in the ceremony. The tea house (chashitsu) is simple and appears almost empty. Only the tatami and a small sunken square hearth ( ro) that covers the floor, the t okonoma, with a hanging kakemono drawn with the kanjis of harmony, respect, purity, tranquility ( wa kei sei jaku), and the arrangement of a single flower (chabana). It is said that the tea house waits in this way, silent and serene, to be filled with the feelings of the hearts of the participants of this traditional ceremony.

The harmonious combination of preparing tea for the visitor, in the simple atmosphere of chashitsu with utensils that reflect art, history and the season of the year; offering those opposite flavors like a sweet before sipping the tea, to erase some of the bitterness of the matcha ( like the moments that sometimes fill our lives); thanking, by lifting the bowl before drinking it, all those who made the ceremony possible (farmers, artisans, teachers); and doing it with the respect that those who accompany us deserve, make the tea ceremony an art that is worth preserving and practicing.

Each utensil reflects the beauty of art developed for hundreds of years. The movements that we usually make when preparing tea, suddenly, in the ceremony, the faint touch of things with our hands is felt like a soft, fresh breeze on the face. Folding the silk handkerchief, cleaning things, pouring water, stirring tea, everything becomes art, even silence and the few sounds that are heard.

You can only hear the soft rubbing of footsteps on the tatami, the cleaning of the edges of the natsum e with the fukusa , the faint touch of the chashaku on the edge of the chawan, the soft sound of water being poured with the hishaku and the faint “ tac” when leaving it on the futaoki ; the almost imperceptible touch of beating the chasen mixing the water and matcha, the shaking of the remnants of the tea that remains on the fukusa, and the quiet voice of the exchange of words between the teishu -san and the shou okyaku-san .

The only thing that interrupts this silence is the loud noise that the visitor makes when taking the last sip of tea, expressing his way of saying that he is oishii. Remember, the next time you go to a ceremony, the last sip of tea should be loud, very loud, and that “each encounter should be treasured because it will never be repeated again” ( Ichi-go ichi-e) .

This thought of ichi-go, ichi-e has taught me to treasure every encounter. The one I can never forget is the memory of visits to my obaachan. When we visited her she would take out the dishes that she always kept in her living room. After serving us tea, rolls and sweets with a smile, he would remove the dishes he had brought from Japan and, with great care, as if caressing them, he would wash them and put them back in their place.

That care towards his things surprised me when I was a child. I remember that his look changed. Nostalgia and memories of her town and her family in Kumamoto invaded her.

The first time I attended a full tea ceremony was when my mother was president of Fujinkai and invited me to witness. The tea ceremony is held every year in the first week of November at the Peruvian Japanese Cultural Center during cultural week. I was impressed by the smooth elegance of each movement when preparing and drinking tea. I decided it was something I should learn and practice.

I enrolled in the Urasenke school that teaches the ceremony at the center and, during my breaks from hospital duty, in addition to the usual books I read the philosophy that accompanies this ceremonious and significant act.

The Peruvian Japanese Polyclinic was nearby, so before starting my treatment in the office, at dusk, I would sit for a few minutes to enjoy the serenity provided by the tea house (chashitsu) and the beautiful nature that surrounded it.

To go to the tea classes, you reach the chashitsu walking along a narrow path of gray stones that borders the garden with tall pine trees, planted during the visit to Peru of the now former emperors of Japan in the sixties, which I attended, amazed. and surprised, with my parents when I was a child.

I observe for a few minutes the fast and colorful carp in the lagoon. I cross the bridge that takes me to the tea house and I am filled with the sound of the birds in the trees and in the sky, and I listen to the murmur of the soft fall of the water of the small waterfall and the peace of silence that is desired, even in the midst of nearby urban noises. Then I taste the beautiful little sweet that the sensei gives us before drinking the tea, to reduce the somewhat bitter taste of the matcha, which I drink until the loud last sip that tells him how good and pleasant the tea was.

It is true that all movements have a specific objective and are necessary, systematic, simple, smooth. But in each of these I see respect for people, objects, nature and the seasons of the year, and I feel the harmony, purity and serenity that my heart has always longed for. In the tea ceremony you can appreciate the effort of the Japanese to achieve maximum simplicity and refinement in the movements that symbolize true beauty.

Finally, I recognize that I am just getting started in the Tea Ceremony and I still have much more to learn, but now I know that each encounter, each moment in life, is precious, unique and unrepeatable. And, what was once everyday for me, today has become art.

Bibliography:

“ Japanese Tea Ceremony .” (Wikipedia)

“ Glossary for Tea Ceremony .” (The Japanese Tea Ceremony)

"Tea ceremony ." (Traveling through Japan)

Surak, Kristin (2013). Making Tea, Making Japan: Cultural Nationalism in Practice . Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-8047-7867-1.

Kaisen Iguchi Sōkō Sue; Fukutarō Nagashima, eds. (2002). " Jukō ." Genshoku Chadō Daijiten (19 ed.). Tankōsha.

Rupert Cox, The Zen Arts: An Anthropological Study of the Culture of Aesthetic , 2013.

Glossary Chadoo / Sadō(茶道): Way of Tea |

© 2023 Graciela Nakachi Morimoto