I have written many articles on this website, "Discover Nikkei," about Japanese people in Latin America and Japan. I have nothing but gratitude for having had the opportunity to write down stories that should be recorded, such as the " City of Flowers: Escobar " in the suburbs of Buenos Aires where I was born and raised, and my own experience serving in the Malvinas War . However, this is the last article in this series. In this final article, I would like to introduce the life of my late father, who "emigrated overseas."

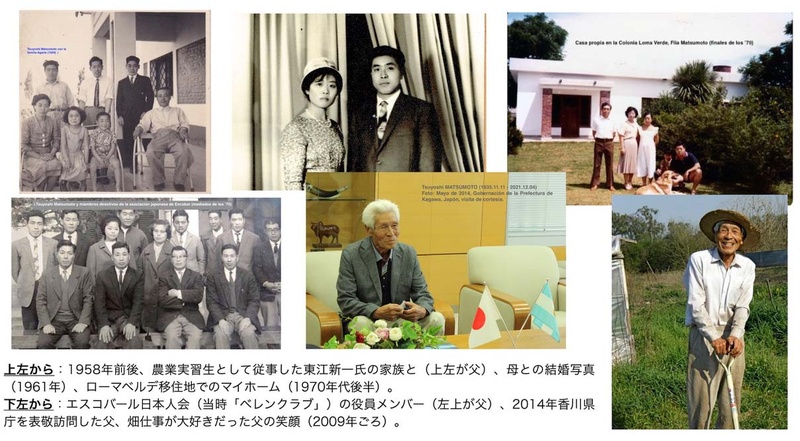

My father, Matsumoto Tsuyoshi, was the first postwar Ministry of Foreign Affairs overseas agricultural trainee, traveling to Argentina on the "Amerika Maru" at the age of 22 in 1957. He spent the first three years working at Agarie Shinichi's vegetable farm in the southeastern suburbs of Buenos Aires. Making full use of the knowledge he had acquired at the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry Agricultural Research Institute's Horticulture Department before emigrating, he succeeded in cultivating tomatoes for shipment before Christmas, which was very rare at the time. Agarie, the manager, expanded this cultivation method and is said to have made considerable sales.

However, my father's monthly salary at that time was 800 pesos, which was the equivalent of two crates of tomatoes, and he proposed sharecropping in line with his success, but unfortunately it was not accepted. Therefore, he decided to become independent, and when he married Kazuko, who would become my mother, he moved to the "City of Flowers" of Escobar (50 km north of Buenos Aires), and had three children.

My mother, Kazuko, was a classmate of my father's sister and through that connection she came to Argentina in 1961. We are three siblings, but my brother and I were born prematurely, so I heard that life was difficult at first. However, with the help of Japanese people in the neighborhood, we were able to raise all of our children healthy.

As many of the trainees have said, some were able to get off to a good start thanks to the support of their early patrons (employers), while others, like my father, started from scratch. My father didn't seem to have much interest in growing cut flowers, but with the support of his seniors from the same prefecture and immigrants who had been successful in flower cultivation before the war, he rented land, built a greenhouse, and made a living by growing carnations and other flowers1 .

Before I started kindergarten, my father bought a scooter. I remember standing in the small space in front of the scooter and my mother sitting in the back, and we often went out together. When I started elementary school, my father bought a used pickup truck that was also useful for work. I wanted to ride in the truck, so I cried and begged him to go shopping or run errands with me.

There were many Japanese people who had moved from Paraguay near my house, and we helped each other out. One of my classmates at elementary school was also a transfer student from Paraguay.

Escobar had a Japanese community of 140 households and 500 people. Thanks to this, there was a Japanese language school that taught three hours a day2 , and from elementary school onwards my father was actively involved in parent-teacher and producer groups, served as a secretary for the local Japanese Association, and later served as chairman of the Kagawa Prefectural Association for six terms, fulfilling his role as an advisory board member until his death at the age of 87. The town also had a nursing home for Japanese people called Nichia-so, where my father served as an executive officer for many years.

All these positions were unpaid, and I remember my mother complaining a lot about the farm being the busiest when my father was in his 30s and 40s, and the business was tough during poor harvests. During summer and winter vacations, I helped out on the farm for the same hours as the employed peons (farm laborers). It seems that this was the situation for all families involved in running Japanese community organizations.

When I was in the third grade of elementary school, we moved to the JICA-developed "Roma Verde Colony 3 ," 9 kilometers from the town. My father also cultivated carnations at first, but he invested a lot of money in the equipment (glass greenhouses and heating equipment) necessary for cultivating roses and chrysanthemums in the new colony. At that time, many floriculture businesses were expanding, despite being affected by the unstable economic situation in Argentina, and they expected to make a profit, so my father chose the same path.

However, the import of cut flowers from Colombia dealt a major blow to floriculture. So, with strong persuasion from my mother, my father switched to vegetable cultivation, his specialty, and began growing tomatoes and later strawberries on five hectares of land. He also rented land outside the settlement, entered into sharecropping contracts with four or five Bolivian households, and shipped large quantities to the central market and local markets. As a high school student, I used to help unload the goods on my days off, and looked forward to eating "milanesa," an enormous beef cutlet, with my father at a restaurant in the market afterwards.

Escobar has a large Bolivian community, as Bolivians who signed sharecropping contracts gradually invited relatives over and saved up money to buy land. Since the 1980s, Bolivians have increasingly come to dominate the vegetable market, building large producer associations in the north and south of Buenos Aires to facilitate business.4

From the end of the 1980s to the 1990s, Escobar himself began to migrate to Japan to work. Due to excessive debts from previous investments, intensifying competition, economic stagnation, and high youth unemployment, some of my father's comrades and their children had no choice but to repay their debts. Going to Japan to work was a great opportunity.

Fortunately, my family had almost finished paying off our debts thanks to our strawberry farming, and the orchard business was going relatively smoothly after we moved to the settlement. I came to Japan as a government-sponsored student in April 1990, and by staying in Japan after obtaining my degree, I became a part of the "reverse Japanese migration phenomenon." I was also deeply involved in providing consultation services to Japanese workers in Central and South America, which allowed me to use my experience and knowledge to positively benefit the Japanese.

Notes:

1. “Roundtable discussion among men living in the northern suburbs of Buenos Aires,” Kagawa Prefectural Association of Argentina 35th Anniversary Commemorative Book, pp. 13-17, Kagawa Prefectural Association of Argentina, 2005.

2. At that time, Mr. and Mrs. Kono lived in the school and taught first through sixth graders in the morning and afternoon shifts. Many of the second-generation Japanese who studied at the Japanese language school during that time would later go on to work for Japanese companies and public institutions. It also gave them an advantage when it came to studying or training in Japan. There was lunch time and recess, making for a total of four hours, during which students studied Japanese and kanji under strict discipline. There were also school performances and athletic meets, making it a fine educational institution.

3. 15 families settled on 42 hectares of land. Many of them were engaged in growing flowers and ornamental plants. Established by JICA in 1969.

4. “Chapter 3: Argentina’s Multicultural Coexistence Policy – Considering Japan’s Immigration Policy from a Neighboring Country’s Immigration Policy (Bolivian Community),” in Asaka Yukie (ed.), Aspects of Multicultural Coexistence in the Global Era: International Relations Connected by People, Korosha, 2009.

© 2022 Alberto Matsumoto