A year and a half has passed since the COVID-19 pandemic began, but in Japan, seminars on the issue of aging among foreigners have been increasing recently. A symposium held in Nagoya at the end of March this year was a hybrid of face-to-face and online sessions, and I was invited as a speaker to talk about "old age for the elderly in the South American community in Japan." The symposium introduced examples of Korean and Chinese oldcomers, as well as the efforts of Filipinos, and was very interesting.

In particular, we South Americans and Filipinos have little opportunity to think deeply about the concepts of "old age" and "end-of-life planning," and it turns out that these concepts are culturally unfamiliar to them. According to Kinoshita Takao (Wang Rong), representative of the organizing group, Chinese communities have been preparing for old age, establishing group homes, utilizing nursing care insurance, training care workers and care managers who can understand languages and different cultures, and securing cemeteries as part of their end-of-life planning. It was quite a shock, but it reminded me that Japanese who have emigrated overseas have also established various systems related to their lives and secured plots for Japanese people in city-run cemeteries.

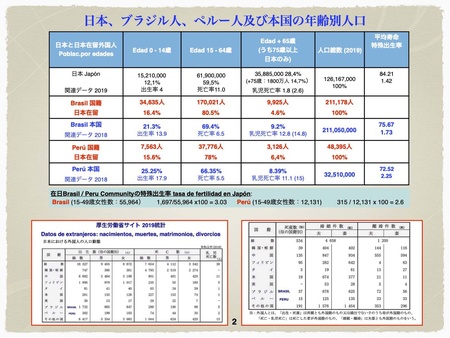

However, I don't think such preparations are necessary in Japan today. Almost everything is in place in Japan, and services are provided according to need. To use these services, you need to save up a certain amount of money, but even foreigners can get what they need (in the worst case scenario, cremation and burial after death can be handled by local government welfare services). Japan has a low birth rate and an aging population, with a fertility rate of 1.34, and people aged 65 or older making up 28.4% of the total population (about 36 million people). The average life expectancy is 84 years (81.64 for men and 87.74 for women), most people receive pensions, and the savings rate of the elderly in general is high. The medical expenses burden for this group has risen dramatically, and the self-payment rate will surely continue to rise in the future, but many people are still able to receive medical services, which leads to longevity.

According to the Immigration Bureau's statistics for December 2020, there are 272,279 South American residents in Japan, or 9% of the foreign population. There are 208,538 Brazilians, 48,256 Peruvians, 6,119 Bolivians, 2,966 Argentines, and 2,131 Paraguayans. If we tally up the number of people aged 65 or older, there are 9,925 Brazilians, which is 4.6% of the total, and 3,126 Peruvians, which is 6.4%, but for some reason, there are 16.1% (984 people) of Bolivians, 6.8% (206 people) of Argentines, and 1.8% (40 people) of Paraguayans. The elderly rate of South Americans is around 5%, and looking at this number alone, it seems that there is no need to worry too much at this point. However, looking at the 50s in the same statistics, we can see that in a few years, the number of people of retirement age or pension age will increase dramatically. The proportion of elderly people will continue to increase, with the age group of 65 and over accounting for 9% to 11%.

On the other hand, the current fertility rate of Brazilians in Japan is 3.03 (1,732 births in Japan), and that of Peruvians is 2.6 (382 births). As seen in many foreign communities, the fertility rate will eventually fall further, and as generations progress, it may fall to the same level as the fertility rate of Japanese people. As an aside, even in Japan, the divorce rate and illegitimate children among Brazilians and Peruvians are quite high, and the Consulates General in Tokyo and Nagoya register many of these infants (until a few years ago, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare also published the rate of illegitimate children among foreigners, and when broken down by nationality, the rate for Peruvians and Brazilians was over 30%. This is a much lower figure than the 50% or so rate in their home countries, but the rate of illegitimate children in Japan is 2.23%, which is 15 times higher). 1 Looking at these figures, it may be that people from South America rarely plan for their retirement.

However, since the Lehman Shock in 2008, the idea of settling down has become stronger even among South Americans, and they have become more conscious of joining social insurance to receive pensions. In order to spend their retirement years in peace, they need to contribute as long as possible, even if they are non-regular employees. It is unclear how long they will have to contribute by the time they turn 65, but it is certain that it will be much shorter than Japanese employees.

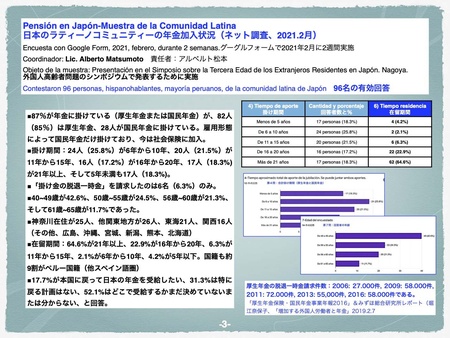

For this symposium, an online survey was conducted among about 100 Peruvians aged between 40 and 65. The survey revealed that 87% of them are paying into a pension, and most of them are paying into the Employees' Pension Insurance under the Social Insurance System. As shown in Table 2, 18.3% have paid into their pensions for 21 years or more, 17.2% for 16 to 20 years, 21.5% for 11 to 15 years, and 25.8% for 6 to 10 years. 42.6% of the respondents were in their 40s, and it is a relief that many of them will be able to continue paying into the future, but we hope that they will continue this attitude as long as possible. Fortunately, unlike Brazilians, Peruvians rarely take advantage of the pension lump-sum withdrawal system2. If you continue to add to your contribution period, you will have some peace of mind in your old age.

In South America, the concept of "retirement planning" is not so common. In the past 20 years, overall income has risen and public medical care has expanded, leading to an increase in average life expectancy to 75.67 years in Brazil and 72.52 years in Peru, but the infant mortality rate is more than six times that of Japan (Japan: 1.8, Brazil: 12.8, Peru: 11.1). In South America, where the informal economy accounts for around 50% or more, there are not many ordinary citizens who trust and pay into the pension system (a survey conducted five years ago showed that 60% of the employed population in Peru was not enrolled in a pension system). In every country, the contribution period to qualify for pension is longer than in Japan, and the amount of pension received varies depending on the system in each country, but the fact that public pensions are often lower than the minimum wage is likely a reason why the proportion of people who use the pension system is low.3

Peruvians and Brazilians living in Japan do not trust their own country's pension system, and even if they are able to contribute, it is very difficult to become eligible to receive benefits while living in Japan (Brazil is the only Latin American country that has concluded a social insurance agreement with Japan4 ). Perhaps because of this, they were initially opposed to the idea of temporary employment agencies joining social insurance in Japan. However, in recent years, they have occasionally asked about extending their contribution period, so it seems that their attitude is changing. However, since the contribution period of 20 years or so may only amount to about 30% of their previous average wage, they will need employment or support from their children to supplement their pension income. Ultimately, some of these long-term foreign residents may have no choice but to rely on public assistance (such as welfare assistance).

From a Latin perspective, there is no need to feel too much of a sense of crisis at this point, but it may be a good idea to at least determine a "path to retirement." Latinos tend not to take the uncertainty of not knowing how long they will live seriously, but as long as they live in Japan, there is a chance that they will live longer than their compatriots in their home countries. This is because the average life expectancy in Japan is 10 to 12 years longer than in South America, Japan has a well-developed medical system and food education, and there are many programs to prevent lifestyle-related diseases.

Japanese people have a different view of life and death than Japanese people, and it seems that they don't even discuss temples and graves, which are often mentioned in "end-of-life activities." For now, the first priority is to encourage them to attend preventive care classes and make efforts to help them spend their retirement years as healthily and happily as possible.

This is an issue that worries ordinary Japanese people, but many are aware of the need to extend the retirement age, extend the period of pension contributions, increase savings without applying even if eligible, secure the possibility of working part-time or on a contract basis even after retirement, and prioritize maintaining health to avoid medical expenses. However, over the past decade or so, non-regular employment has increased and lifetime average income has not increased, so pension contributions are proportionately low, and the reality is that many people have little savings. Various policy improvements and reforms are being discussed, but this is not something that only affects foreign residents.

Notes:

1. The rate of illegitimate children in Japan is low, at 2.3%. On the other hand, the rate is much higher in Latin America and Europe, with many countries exceeding 50%.

" Will an increase in children born out of wedlock solve Japan's declining birthrate problem? " (Newsweek, July 13, 2017)

2. The pension lump-sum withdrawal system applies only to foreigners, and allows them to claim a portion of the pension they paid in Japan back from their home country. The number of cases has been around 60,000 per year for the past few years, but the cost of claiming in Brazil has always been high.

" Lump-sum Withdrawal Payment System " (Japan Pension Service, April 1, 2021)

3. Alberto Matsumoto, " The Pension Situation in South America and the Pension Issues of South American Workers in Japan " (Discover Nikkei, November 23, 2016)

CNN Español, " American Latinos face more than half a million for pensions " (CNN, October 11, 2019)

" Going to a vacation home in America, living with my family and living with my kids " (Telemetro.com, July 4, 2018)

4. " Social Security Agreements " (Japan Pension Service, March 27, 2020)

© 2021 Alberto Matsumoto