Introduction

In December 1943, when loyal Japanese Americans were leaving concentration camps and relocating to cities in the Midwest such as Chicago, Cleveland, and Kansas City, four Japanese Issei men were arrested in Chicago by the FBI. They were Charles Yasuma Yamazaki and Frank Masuto Kono, who had been Chicago residents for more than twenty years, and Soyu Matsuoka, a Buddhist priest, and Robert Hajime Shiomi, a medical doctor from Oregon. Matsuoka and Shiomi were new to Chicago.

Matsuoka came to the U.S. in June 1940 and lived in Southern California and Denver, Colorado until July 1943, when he arrived in Chicago. Shiomi was born in Japan but educated in Portland, Oregon. In September 1942, he was incarcerated at the concentration camp at Minidoka, Idaho, then transferred to the camp at Manzanar, in California. He was given an indefinite leave in May 1943 to practice medicine in Chicago and relocated directly from Manzanar. Out of these four Japanese who were arrested, only Frank Masuto Kono, secretary-treasurer of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society in Chicago, was transferred to Detroit by train for interrogation on December 2, 1943.1 Why Detroit? Probably because Detroit was where Naka Nakane had founded his political organization, “The Development of Our Own,” to spread propaganda designed to agitate and organize African Americans.

Nakane had been under the U.S. government’s watch for a long time, as he was suspected of being a member of the Black Dragon Society. The Black Dragon Society was a political group founded in 1901 in Tokyo, with a membership of Japanese elites from every part of society, including politics, business, academia, and the media. Due to the Black Dragon Society's influential power in advocating for the “unity of darker races” in Japan and beyond, the U.S. government had been closely watching the Society. The Society was especially scrutinized and tracked in the 1930s, under FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, whose previous job had been to gather evidence on radical groups for the U.S. Justice Department.2

In Chicago, the government looked for subversive activities among Japanese and radical African American collaborators, who had worked under Naka Nakane in the late 1920s and 1930s. One such man, Ashima Takis, a Filipino that Nakane had recruited to pose as Japanese, published a letter titled “Universal Brotherhood” in the May 27, 1933 Chicago Defender, claiming that Japan was the leader of Asia. A detailed explanation of Japanese advocacy for the “unity of darker races” in the letter indicates that the real writer of the letter might be a Japanese national such as Naka Nakane. Various leaders of local Japanese groups in Chicago reported to the authorities that there had been no Japanese active in recent years within radical black organizations such as Allah Temple of Islam, and that if there had been, they must have returned to Japan long ago.3 Nevertheless, someone in Chicago secretly reported that Frank Masuto Kono had ties to the Black Dragon Society.4

Chicago's Japanese and the African American communities

Even before Naka Nakane came to the Midwest, there were Japanese living in Chicago who had a keen interest in the African American community. Some newspapers in Japan even published articles on the infamous race riot in Chicago in 1919 that resulted in thirty-eight people dead, which they had received through reports from the Reuters news service.5 A journalistic report and photographs, taken by Jun Fujita of the Chicago Evening Post, also appeared in the Maeli Sinbo, the official Korean language newspaper of the Japanese colonial government in Korea.6

In one of the articles published in Japan, a Japanese man who had studied in the U.S. was asked to comment on the 1919 race riots, and he answered that the Japanese had more intimate sentiments toward African Americans than whites did.7 Furthermore, a member of the Chicago Japanese Association reported a local incident in a private letter to his friend in Japan and the contents of the letter were published in a well-known Japanese newspaper, the Yorozu Choho.8 The account describes an incident in June 1920, in which Grover Redding, the leader of the cult group, “Black Star Order of Ethiopia,” burned a U.S. flag.9

In Japan, a biography of Abraham Lincoln written by Kaiseki Matsumura was published in 1890. Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Stowe was translated in 1897, and in 1908, Midori Ogouchi introduced Booker T. Washington to Japan in his book, Ijin no Seinen Jidai (Youth of Great Men), an abridged and edited translation of Washington’s autobiography, Up from Slavery.

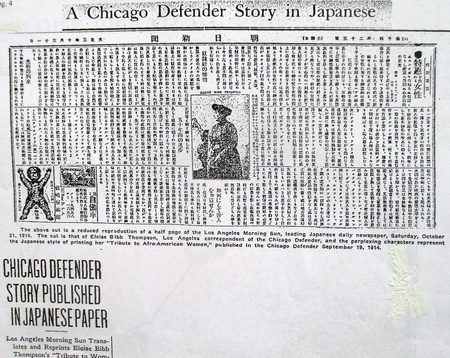

Stories of African American women also appealed to the Japanese. The article “Tribute to Women,” written by Eloise Bibb Thompson and published in the September 19, 1914 Chicago Defender was abridged, translated into Japanese, and published in the October 31, 1914 Japanese vernacular newspaper in Los Angeles, the Asahi Shimbun. The Japanese language article was reprinted along with an English explanation in the November 21, 1914 of the Chicago Defender. In short, the Japanese found a reflection of themselves in these stories of African Americans’ struggles for equality, as they too had been making desperate efforts to achieve equality with European, white civilization ever since Japan was forced open to the world in the mid-19th century.

Notes:

1. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, page 320

2. Michaeli, Ethan, The Defender, page 126

3. Hill, Robert A., The FBI’s Racon, page 545

4. Ito, page 321

5. Yomiuri Shimbun, August 7, 1919, Yorozu Choho August 6,7 and 8, December 19, 1919

6. Maeli SinboDecember 15 and 18, 1919, Courtesy of Chris Suh

7. Yomiuri Shimbun, August 7, 1919

8. Yorozu Choho, August 1, 1920

9. Chicago Daily Tribune, June 24, 1920

© 2021 Takako Day