During the war, ten Japanese-American internment camps were established in California, and in addition to the Japanese-Americans who were initially interned there for geographical reasons, those who were deemed to have no loyalty to the United States were later gathered there. On the other hand, those who were deemed to be loyal by the government were transferred to other internment camps.

The issue of loyalty or disloyalty is difficult for many people to decide as individuals, and it is not easy to judge it from the outside. The Moriguchi family lived in Tacoma, so they moved to Tule Lake, but they never moved elsewhere.

It is not clear what political views Fujimatsu Moriguchi, the family pillar, held or how he was perceived by the government, but it is hard to imagine that he had any intention of settling down in America at this point.

By the end of the war, Fujimatsu and Sadako had five children, including their eldest son Kenzo, who was 12 years old, and Tomoko, who was born just after the war, making a fresh start for six people. Where would they go after leaving the internment camp? Fujimatsu chose Seattle, not Tacoma, where he had set up shop before the war. He decided that Seattle offered greater business opportunities for the future.

The Tule Lake internment camp was closed in March 1946, the year after the end of the war, but about two months before the end of the war, Fujimatsu left his family at the camp and went alone to Seattle. The former Japantown had completely changed over the years of war since the Japanese were sent to the internment camps. However, this was only temporary, as Japanese people gradually returned from the internment camps and the town regained its vitality. The situation at that time is described as follows in "A Hundred Years of Japanese Americans in the United States" (Shin Nichibei Shimbunsha, 1961). Although some of the expressions contain racial prejudice, we will present them as they are.

"The commercial area around the corner of Main Street and South 6th Street, which had become a den for black people during the war, was quickly bought back by Japanese Americans and became a Japanese commercial area once again."

One of these was the fish wholesaler "Maine Fish Company," where Fujimatsu had worked shortly after arriving in Japan. The company was started by the Kihara family before the war, and soon after Fujimatsu found work again, he bought a house for his family around 12th Street, about 4 kilometers east of the center of the old Japantown, a little way off Yesler Street. It seems he used the money he had saved up before the war.

"I think he deposited it in the bank, but I'm not sure," says his second son, Tomio.

The house was a two-story wooden structure with a basement. It was built on a long, narrow plot of land measuring about 330m² and had three bedrooms. Once the house was ready to welcome the family, Sadako's wife and children, who had been in the internment camp, joined them in their new home. The house was later expanded to five bedrooms, and small outbuildings were built at the front and back, which were rented out to friends and where Sadako's younger brother lived.

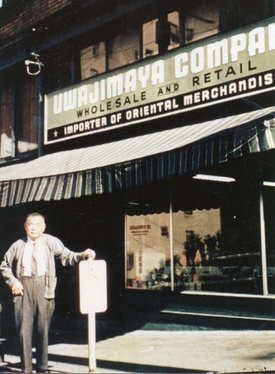

He rented a store and opened Uwajimaya with his family.

Meanwhile, Fujimatsu quit the Main Fish Company about a year later and started "Uwajimaya" again. The store was located on the corner of Main Street and 5th Avenue in Japan Town, renting a corner on the first floor of a 5-6 story building owned by a Japanese. As is often the case, the upper floors were used as a hotel. The space Fujimatsu rented was used as a grocery store by a Filipino during the war, but after the war, the owner decided to close the store due to poor economic conditions, and Fujimatsu set his sights on the space and rented it.

It was a long and narrow space with a width of about 3 ken and a floor area of about 30 tsubo (100 m2), with a sales floor on the first floor and a kitchen in the back, and a basement where we made kamaboko and other things. There was also a small second floor that we used as a storage space.

As before the war, the store continued to sell groceries and miscellaneous goods, and when the store opened, Sadako walked from home to work every day, preparing meals for her family and servants both day and night. The children also helped out with the work in the store. Kenzo, now in junior high school, and Tomio, who was in elementary school, also did a variety of jobs, including serving customers. For customers who came to buy rice, they packed it into small bags of five pounds each, refilled soy sauce into small barrels, and also swept the floors. There was plenty to do. The store closed around 6 or 7 o'clock.

Most of the customers were older second-generation Japanese-Americans, rather than first-generation Japanese-Americans, and they mostly spoke Japanese. They were all locals, and their families knew each other, so the restaurant felt like a small Japanese-American community. At the time, Tomio felt that the atmosphere was "very friendly and welcoming."

In addition to these regular customers, the store was also visited by "war brides" from Japan who had married Americans and were very surprised to see Japanese food available.

With mainly Japanese and Japanese-American customers, the new Uwajimaya continued to thrive, and Fujimatsu and the Moriguchi family continued to lead busy lives.

(Titles omitted)

© 2018 Ryusuke Kawai