One day in the early 1980s, my Japanese mother took my sister and me to an International District gift shop. A middle-aged Japanese American man working there glanced briefly towards us, before turning away apathetically. His body language seemed to indicate a reluctance to wait on us. I looked at my mother and, without the necessity of my uttering a single word, she said, “He not like me.”

Then, pointing at us, her two half-black daughters, she declared in her broken English, “He see I have you two. He know I am war bride.”

Even though I’d heard her use that phrase before, I knew it was not something she was proud to be called. As I stood there reflecting, I realized my mother meant that the Japanese American man didn’t like the fact that she had obviously married someone outside of her race, likely an American G.I. But the irony was he wasn’t living in Japan. Might not the Japanese in that country have considered him as much a traitor for living in America as he thought my mother was for marrying a non-Japanese? Or maybe it wasn’t the same if you left your home country, but married someone of the same ethnicity. I’ve often wrestled with those thoughts in the decades following that 1980s incident.

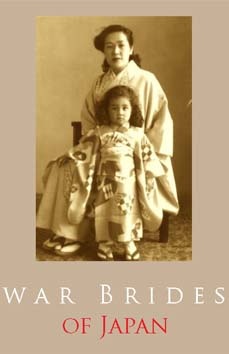

In the case of Japanese “war brides” like my mother, women who wedded American military men, they were guilty of both marrying an outsider and leaving their country. Considered disloyal by some Japanese nationals for wedding their former enemies, they were also considered disloyal by some Japanese Americans for marrying Americans that were not Japanese. It’s a complicated issue that my documentary War Brides of Japan will address. I also want to eradicate the stigma attached to the term “war bride,” often fallaciously interchangeable with “prostitute.”

During the Allied occupation of Japan following World War II, the U.S. military became the largest employer in the country. The devastating bombing raids that destroyed the infrastructure created food, housing, and transportation shortages. But more overwhelming was the loss of over two million Japanese men. Like a lot of women, my mother had to go to work. Hired at an Army base, she was taught to make and sell sandwiches to American soldiers. The bonus was that her boss, a sergeant, allowed her to take home leftovers to feed her hungry family and neighbors. That ambiance of respect towards Japanese by Americans had been ordered by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and implemented by General MacArthur.

As some Japanese interacted with their friendly occupiers, relationships began developing. And, as the primary wage earners, Japanese women must have felt liberated—tossing their geta for the high heels and nylon stockings that Americans brought. Like some feminist prototype, they traded their kimono for wide poodle skirts, took up smoking cigarettes and began dating their former enemies.

More importantly, Japanese “war brides” inadvertently helped new laws into legislation. Military husbands wanted to bring their wives back home to the United States, so the War Brides Act of 1945 was enacted and overturned the Immigration Act of 1924, a law that barred Asians from entering the United States. Without realizing it, Japanese “war brides” helped usher in a new mandate that allowed some 12 million Asians to immigrate to America over time.

By forgiving and marrying their former enemies, Japanese “war brides” also proved that love has the power to transcend war and hate. What’s truly remarkable is that most married either a black or white man. The rare exception was when a “war bride” wed a Japanese American intelligence officer stationed in Japan for his bilingual skills. Nonetheless, most “war brides” entered into interracial marriages and gave birth to mixed-race babies.

Never having been in the United States before, they were unprepared for the overt racism, Jim Crow, and xenophobia prevalent at the time. In fact, most were clueless about Executive Order 9066 and how Americans of Japanese ancestry had been forced into incarceration camps. Without intending to, “war brides” even helped perpetuate Japanese culture by continuing to embrace it when interred Japanese Americans were forced to destroy aspects of it.

Until 1967’s Loving v. Virginia, it was illegal in 16 states for any white person to marry anyone except another white person. With anti-Japanese hysteria permeating the country, “war brides” living in civilian neighborhoods were vulnerable, often verbally accosted and even accused of starting the war despite having had no say in it. Those living on military bases fared better as they enjoyed the camaraderie of other “war brides” residing nearby.

What is particularly noteworthy is how much hardship most “war brides” endured. Some were disowned by their Japanese families for marrying a foreigner, and then rejected by their American in-laws for being a foreigner. Sailing on ships for weeks, then arriving in a strange country without the support of their immediate families, they had to overcome cultural and language barriers while raising biracial children they hoped would assimilate and be accepted.

The first “war bride” was recorded in 1947. While the bulk arrived in 1952, anyone marrying an American G.I. through 1965 was included in that category. During those days, air travel was uncommon, long distance telephone calls were expensive, and “war brides” communicated with their families in Japan through writing letters.

In August, a cameraperson and I plan to visit six cities in three states to interview eight participants, including a historian, a couple of war brides and their adult children. We’re currently fundraising for equipment and travel expenses. As “war brides” head into their mid-80s, it’s imperative that we record their stories now. The world needs to recognize their important contributions to the Asian American landscape that we see today so that no one will ever look at them with the kind of apathy my mother tolerated that day in the gift shop in the early 1980s.

Please help us make the War Brides of Japan documentary by donating cash or in-kind services and supplies at:

https://fromtheheartproductions.networkforgood.com/projects/15778-documentaries-war-brides-of-japan.

For more information, visit www.warbridesofjapan.com.

* This article first appeared in the International Examiner newspaper on July 21, 2016.

© 2016 Yayoi Lena Winfrey / The International Examiner