Read Part 1 >>

AMOUR AT FIRST SIGHT

Whatever the reasons Perry and supporters had, to force the “opening of Japan,” they never even imagined what effect their action would have on Europe’s and, eventually, America’s creative minds. It was as if breaching the already porous Sakoku had caused an en-masse escape of all the Japanese muses.1 And, it served the West right, because it happened at a most appropriate time.

In France, the Seat of World Culture, the sanctimonious Académie des Beaux-Arts, and the sterile government-sponsored Salons had forced upon pictorial artists a suffocating nightmare. The younger, the restless, the marginalized refusé, and the avant-garde painters (Ah; ces Intransigeant!!!) all were agonizing. Salvation came, would you believe it, through the inexpensive Japanese ukiyo-e prints. More than anything else, ukiyo-e had the greatest impact on French pictorial artists; they helped them intuit anew, better reflect their own perceptions, and bring about the democratization of fine art.2

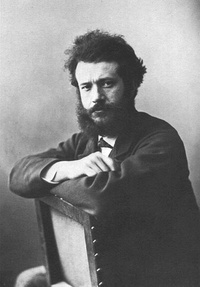

The legend persists that, around 1856, at the workshop of his printer August Délatré, French artist and print-maker Félix Bracquemond, (1833-1914) came across a page from the Hokusai’s sketchbook Manga. Apparently, the book had been used as packing for a consignment of porcelain. So enthused became Félix that he decided to get the book at all costs, and he hounded Délatré until he got it. Fascinated with what he had discovered, he became a fervent evangelist for the revival of French pictorial art, along the lines of his findings in ukiyo-e.3

However, since 1855, art critic Philippe Burty, (1830-1890) had also begun eagerly collecting Japanese art. By 1875, he had more than 2500 Japanese objects, including six-hundred pictorial books,4 which he shared with his friends, including Bracquemond. Several other artists, writers and critics also became fascinated with the Japanese prints, and helped popularize them. In 1862, Monsieur and Madame Desoye’s started their Oriental curio shop La Jonque Chinois in Paris. La Porte Chinoise, and Au Celeste Empire soon followed suit, and the French public’s interest in Japanese prints skyrocketed.5

In 1862, England opened its International Exhibition, the Great London Exposition, as a showcase for its own industrial and artistic accomplishments…and those of other nations. Due to shaky Sakoku still ruling, Japan was not asked to attend. However, Sir Rutherford Alcock, (1809-1897), the retired first British Minister to Japan, exhibited a trove of Japanese pottery, lacquer, bamboo and ivory crafts he had lovingly collected during his years of service. The show revealed how exquisite Japanese decorative arts were as compared to the soulless mass products of the Industrial Revolution.

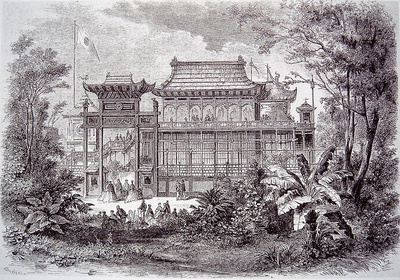

The huge success of Sir Rutherford’s Japanese Pavilion made France yellow with envy; and five years later, Japan was officially invited to participate in the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle. Fervently supported by the Meiji government,6 the Japanese exhibit dazzled the millions of curious who visited it.

Awe about Japanese arts and artisanat7 turned into frenzy. Everybody had to have a doll, a fan, a lantern, a scarf, a box of incense, a netsuke, a bibelot, even just a photo or postcard. Or if one could afford it, a gaudy kimono and a parasol. Every society lady had to hold her own Salon Japonaise; and every major department store had to have its section on japonaiserie. The fad so irritated the French artists’ Japoniste clique that writer-art critic Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896) ranted: “The taste for chinoiserie and japonaiserie! We (the de Goncourt brothers)8 were the first to have it. A taste that nowadays is manifest everywhere and in everyone, even in imbeciles and bourgeois women.”9

Notes:

1. See David Almazán, “La Seducción de Oriente: de la ‘chinoiserie’ al ‘japonismo’.” ARTigrama 18. University of Zaragoza, 2003, 83-106.

2.Yoko Yano, JAPAN-An Illustrated Encyclopedia, (New York: Kodansha America, 1993), 680-1. See also Elizabeth R. Nash,. Edo Print Art and its Western Interpretations, Master Thesis. (College Park: University of Maryland, 2004).

3. Asai Ryoi, (1612 – 1691) the first Japanese professional writer, upended the traditional Buddhist philosophy with his redefinition of ukiyo: Living only for the moment… See Keene, Donald, World within Walls, (London: Secker & Warburg, 1976). 156-66. See also Klaus Berger, Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). Then, for a totally refreshing view, see Michael Hoffman, Japan’s First Pop Culture, The Japan Times online; 2-13.2011.- http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fl20110213x1.html

4. For images of some of the more recent books, see David Humphries’ article “Four Remarkable Books from Kyûshun-dō”, in DARUMA 70. Spring, 2011.

5. Alan Scott Pate, Japanese Dolls: The Fascinating World of Ningyo, (North Clarendon, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2008; 32.

6. Akiko Takenaka, The construction of a war-time national identity, Master thesis: Master of Science in Architectural Technology (Boston: MIT. 1990), 16/18.

7. Toshiyuki Okuma, “Ivory Carving Okimono for Display in the Meiji Era-Halfway Between Plastic and Other Forms of Art,” DARUMA 69. Vol 18 No.l : 21.

8. Parenthetical addition mine.

9. Berger, 11. Here’s a personal observation: In our modern days, M. de Goncourt’s uncouth ranking of bourgeois women in a category below imbeciles would cause him quite a few nightmares.

© 2012 Edward Moreno