The second part of this series will tell the story of another fascinating individual with a tremendous contribution to Japanese American history. Shigeru “John” Nitta was born in Seattle in 1911, but moved to Japan as a child due to his father’s illness. He eventually returned to the United States (specifically Southern California), where he graduated from San Pedro High School in 1933. He soon moved back to Japan and studied chick sexing, which had recently been established and legitimized at the University of Tokyo.

The goal of chick sexing is to be able to determine the sex of a newborn chicken. Females would be kept for producing eggs, while the males would be discarded. Ultimately, this would save chicken hatcheries from waiting over a month for easily identifiable sexual characteristics to develop.

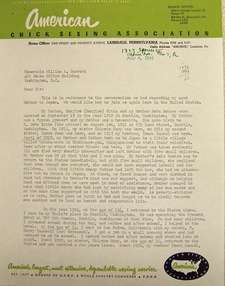

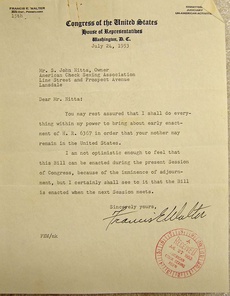

John Nitta opened up the first chick sexing school in the United States in Los Angeles in 1937. By 1940, he had also established schools in Boyle Heights and Terminal Island. However, soon after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 and the subsequent lockdown placed on Terminal Island, Nitta chose to immediately move his school away from the west coast. Perhaps surprisingly, the new permanent location which he chose for his school was Lansdale, Pennsylvania.

Over the next couple decades, Nitta’s American Chick Sexing Association (“Amchick”) became extremely successful and highlighted how Japanese Americans were contributing as productive workers in American society, especially following World War II. He went on several business trips that literally took him around the world, and he was internationally known in his field.

Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, Nitta was active in his community and routinely donated towards many charitable causes. He was once featured in Esquire Magazine and even served as an executive of the Takashimaya department store, which presented him with an opportunity to meet Prince Akihito.

Clearly, the story of S. John Nitta deserves a space when discussing Japanese American pioneers. Furthermore, so many aspects of his life speak against the “grand narrative” of Japanese Americans, and especially of west coast Niseis. For example, Nitta was a kibei, and this unique identity was instrumental in helping him navigate both Japanese and Americans business cultures. Also, since he moved to Pennsylvania immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, he was not incarcerated with the rest of the Japanese Americans during World War II.

However, there is one particular caveat to the telling of this history. The story of S. John Nitta was not one that I came across by chance while perusing the archives. Instead, it literally was placed in front of me when it was delivered in a USPS priority shipping box. As the saying goes, “history is told by the victors,” and obviously Nitta was victorious in life. In no way am I trying to diminish the historical importance of his story, but due to the overwhelming amount of awards and accolades that Nitta received, it almost seemed too perfect of a story to tell.

I personally believe that studying history should be an organic venture that enables the researcher to come to her/his own conclusions through the available evidence. While this mysterious box was just begging to share a Japanese American “Horatio Alger” tale of success against all odds, there were plenty of unrelated hidden gems, some which are strictly ephemera, while other definitely warrant a much closer look.

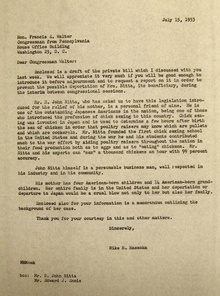

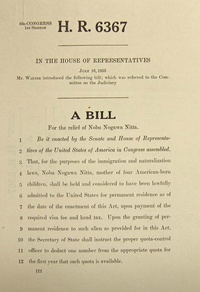

Specifically, we learned that the Nitta family returned to Japan in 1920 when John was just 9 years old. John would later move back to the United States alone. After achieving a good level of financial success, John petitioned to have his mother legally immigrate to the United States in 1953. This is particularly important since it was during the period of virtual Asian exclusion, with a quota of 185 individuals who could immigrate from Japan annually. Nitta’s records include the paperwork towards this eventual approval, as well as the specific government bill that was passed in her name.

The reality is that historians are constantly faced with the struggle of deciding which history to tell. What evidence do we have to support what we deem to be important? Who is our target audience, and which stories would they prefer to hear?

If we apply some of these questions to S. John Nitta, when presented with a limited amount of gallery space, is it better to highlight his business success or his mother’s legal battle? Should we highlight his “model minority” life story, or focus on the aspects of his life that go against the stereotypical Japanese American? Being at the mercy of our museum members and donors, how accountable must we be at telling the stories that they place on our doorstep?

Of course there are never any simple answers to these questions. If we take a step back, we can understand that having too much information and too much documentation is a good problem for a historical museum to have. The truth of the matter is that even though many of the better-known stories in Japanese American history come from successful individuals, most Japanese Americans do not fit in this category.

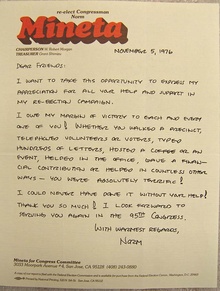

While people like S. John Nitta, Norman Mineta, and even Kristi Yamaguchi are very well-documented, the vast majority of our Japanese American predecessors are not.

* For an excellent JANM oral history interview transcript on S. John Nitta from 1994, click here.

© 2012 Dean Adachi