In the Japanese American National Museum Store lives a five-generation family of teas, dressed in colorful labels, snuggling tin-to-tin on the shelf they call home. This flavorful family is the realization of Maria Kwong’s more-than-a-decade-long dream to bring custom tea to the National Museum. For Maria, the Museum’s Director of Retail & Visitor Services, it had been a dream delayed by the challenge of finding a tea company willing to produce blends in quantities small enough to suit the Museum’s needs.

When Los Angeles tea retailer Chado moved into the Museum’s Terasaki Garden Café space in 2008 and began making specialty teas for Burke Williams and Six Taste, it occurred to Maria that she had finally found her partner. One collaborative effort and many experimental cups of tea later, the Generation Teas were born.

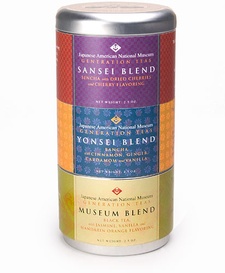

The collection, released late last year, includes teas named after five generations of Japanese Americans, from Issei through Gosei, and an additional Museum blend of black tea with jasmine and mandarin orange. Apart from two exceptions (the Museum, and Rooibos-based Gosei), the blends pair a Japanese tea base with unexpected infusions of flavor like vanilla or citrus for a uniquely Japanese American twist.

The elder of the Generation Tea family is the Issei, made from hojicha, a variety of green tea derived from older leaves that are roasted—rather than steamed like more widely-known varieties—for an earthy taste.

Inside the tin, this blend looks brown and dry, not unlike the hardworking immigrant farmers to whom it owes its name. Paralleling the hardships endured by this generation, the roasting process strips the tea of its youthful grassiness and also some of its caffeine; the result is both strong and mellow, and with the addition of coconut, makes for a smooth, calming cup of tea.

My tea tasting takes place at Chado, across the table from Maria Kwong and the Museum’s Communications Production Manager, Vicky Murakami-Tsuda, the three of us sharing tea from colorful pots strapped with animal-shaped drip-catchers. Vicky passes on the Issei blend. “I’ve always hated coconut,” she says. “I don’t even like to smell it.” Maria brings up cilantro, a food which we’re supposedly genetically predetermined to like or dislike, and from there the conversation moves to coffee and former jobs, shrimp chips, and dementia. “There’s so much nostalgia tied up in smell and taste,” says Maria. “I knew that being able to smell these teas would give people a good feeling.”

After the Issei comes the Nisei blend, a mix of genmaicha and bergamot oil with hints of citrus and vanilla that immediately triggers the imagined voice of my mother that keeps watch from the back of my mind: “Bergamot nanka Nihoncha ni irenai!” I hear. “You don’t put something like bergamot in Japanese tea!” But maybe I’m not giving her enough credit as an adventurous lover of tea.

Genmaicha, a type of green tea flavored with puffs of roasted brown rice, is a staple in many Japanese American homes. For one thing, it has a pleasant flavor—the bright, leafy green of sencha tempered by the toasty flavor of browned rice. It’s also typically inexpensive, “and it doesn’t have a lot of taste, so if you reuse the same teabag over and over, it tastes the same,” jokes Maria. “That’s the Nisei trait of being frugal.”

“It’s mottainai if you don’t!” says Vicky, a Yonsei. “I still reuse teabags.” Bergamot, the spice that gives Earl Grey its distinctive taste, adds a note of perfume to the mild genmaicha, and the two flavors alternate on the tongue, searching for an identity between Japanese and Anglo influences. The citrus, a poetic nod to this first generation born in California, mostly drowns under the more dominant flavors. Vanilla helps to ease some of the tension of this conflicted blend.

Before the Generation Tea collection, the Museum Store had only ever sold coffee, in conjunction with the Kona Coffee Story exhibition in 1997. The coffee wasn’t a big success, due to the fact that most of the Museum’s guests preferred tea. From a retail perspective as well, the leaf-derived beverage made more sense because it coupled naturally with the tea wares already sold in the store. Vicky has fallen in love with one of them, a new infuser shaped like a rubber ducky that floats atop your tea as it steeps.

The next tea we sample is a little bitter, but “that works with the Sansei,” says Maria of her own generation. The Sansei blend brings together two iconically Japanese ingredients, sencha and cherry, which come together with a tangy bite that places this tea miles away from its predecessors. Sencha is the most popular of Japanese tea, though it varies greatly depending on the season of harvest, the temperature of the water used for brewing, and even the vessels used for steeping and drinking this temperamental tea.

Making sencha demands an involved process: warming the teapot, bringing water to a full boil for optimal taste, allowing it to cool again in order not to burn the leaves, pouring the water down the inside walls of the teapot rather than directly onto the leaves, and watching the clock, poised to pour the tea before it sits for too long and becomes bitter.

I admit, I usually lose patience and cut corners on the rare occasion when I drink sencha at home. But knowing their complex demands makes me respect the moody little leaves at the bottom of my cup. More than that, it makes me feel a sense of connection to Japan, a country with wholly inimitable flavors and aesthetic.

It’s funny that this traditional tea forms the base not of the Issei or the Nisei but the Sansei, I tell Maria, the generation that had to work to learn about its Japanese heritage from its war-shocked parents. She smiles, mid-sip. “It worked,” she says.

Since the release of the Generation Tea collection, the Museum Store has noticed an amusing pattern in tea buyers’ purchasing habits: most people tend to buy the tea that corresponds to their own generation. Vicky and Maria both conform to this trend. As for me? “Did you ever think about making a Hapa tea?” Vicky asks Maria. I imagine yerba mate matched with Moroccan mint, pu’erh with Russian fruit tea and cornflower, combinations that would make old world great-grandmothers everywhere spin in their graves.

The Yonsei blend comes close: bancha (the later-harvested sibling of sencha) paired with chai spices cinnamon, ginger, cardamom, and vanilla. Like a typical holiday chai tea but lighter, the Yonsei embodies a generation that is largely mixed, young, and unafraid of venturing into new cultural territory.

The baby of the tea family, the Gosei blend, mixes even more adventurously, shedding the idea of a Japanese tea base completely. Built on an herbal Rooibos tea, the blend “has nothing to do with Japan,” says Maria, but with vanilla, caramel, and chocolate, it’s sweet and completely kid-friendly.

As hoped, being able to smell all six teas and partake in sensory nostalgia has given people a good feeling. So far, most visitors interested in the Generation Teas have gone with a smell-taste-buy method of deliberation: smell the tea in the store, taste a favorite or two in the Chado tea room, and come back later to buy their favorite blend. From a retail perspective, it’s ideal. But it’s also an inspiring experiment in alternative storytelling, through a narrative of taste.

Check out the Generation Teas at the Japanese American National Museum Store.

© 2011 Japanese American National Museum