It has been 80 years since the end of the war, and with almost no living witnesses to the war remaining, it is becoming increasingly important to pass on the truth of history. It is not enough to understand war as an international issue as explained in textbooks, especially when we consider the harsh and brutal truths of how real people were hurt and suffered.

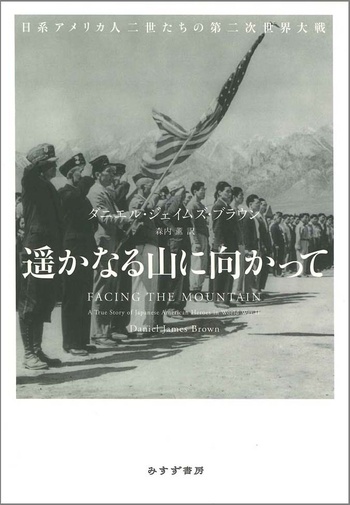

This fact is brought home by the recently published non-fiction book "遥かなる山に向かって 日系アメリカ人二世たちの第二次世界大戦 (Harukanaru yama ni mukatte)" (translated by Kaoru Moriuchi, Misuzu Shobo). The original title is Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II, and it was published in 2021.

Author Daniel James Brown is an American non-fiction writer. His book The Boys in the Boat (translated by Kaoru Moriuchi, Hayakawa Publishing) was published in 2013 and is a million-seller, depicting the activities of the University of Washington rowing team competing in the Berlin Olympics. It was made into a movie in 2023.

FACING THE MOUNTAIN also received high praise, making it onto the New York Times bestseller list and winning the Christopher Award in 2022, which is given to media that affirms the highest value of the human spirit.

As the subtitle suggests, this book describes the hardships that second-generation Japanese Americans encountered and overcame during World War II, primarily through the stories of those who served on the European front as part of “Japanese American units.”

According to the translator’s afterword, the author grew up in the San Francisco Bay area, where his father worked in the florist industry and had many Japanese-American florists and nurserymen as clients. The author remembers that his father was a gentle man, but he would tremble with anger when talking about the war, perhaps because he had witnessed Japanese-Americans having their land taken away and their businesses destroyed.

Perhaps because of this foundation of experience, the author became interested in the history of second-generation Japanese Americans when he met Tom Ikeda, a third-generation Japanese American, and came across the vast amount of material accumulated in Densho, an archive he founded to convey the history of Japanese Americans.

Although the term "non-fiction" is used broadly, it simply means "not fiction," and there are a variety of styles of expression used to depict "facts" and methods of getting to the truth.

"What I wanted to write was not a comprehensive history of the Japanese American experience. . . . What I was trying to do was write the profound stories of individuals who lived through a certain phase in history, and to shed light on history through their stories," the author says, perhaps with a mixture of humility and pride.

In other words, although he is not a historian, he is an excellent writer of non-fiction literature, and he has captivated readers by vividly depicting personal stories based on detailed research, on the historical background and social awareness. Specifically, he makes full use of a wide range of materials, including the vast amount of material from Densho, the words of second-generation Japanese-Americans themselves, records about them, newspaper articles, and more. Of course, this includes facts that he has directly interviewed the people involved.

Many non-fiction works have been written on the subject of second-generation Japanese Americans in America and the war, focusing on the fierce battles on the European front of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Battalion, both of which were made up of second-generation Japanese Americans. However, this book, which combines records from the front and personal histories with the complex backgrounds in which Japanese Americans find themselves, is a first-rate work of its kind.

The story begins on December 7, 1941 (December 8 in Japan), when the Japanese military carried out a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. From that moment on, second-generation Japanese Americans, although they were American citizens with American nationality, were subject to discrimination and hatred, especially those living in the western part of the mainland, and were sent to internment camps.

These second generation Americans search for ways to live their lives depending on their circumstances, such as their family relationships and their psychological distance from Japan. Some protest against the country, some rebel, while others, despite their protests, try to work for the country in order to be recognized as Americans.

This book focuses on the path of four young men after the outbreak of war: Katz Miho from Hawaii, Rudy Tokiwa from California, Fred Shiosaki from Spokane, Washington, and Gordon Hirabayashi from Seattle, Washington, and describes the hardships they faced as second-generation Japanese.

Of the four, the other three, excluding Hirabayashi, served in the military and fought against the German army in Italy and elsewhere. About half of this book is a document of the battles, and it vividly describes how they fought from the soldiers' perspective. Some of the battles they undertook were seemingly reckless, resulting in many casualties. In one famous battle to rescue a Texas battalion from the same U.S. Army, a Japanese-American unit suffered 790 casualties while rescuing over 200 people.

However, it is heartbreaking to imagine that the way they carried out their duties and forged ahead even under such conditions was due to an underlying desire to be recognized as Americans, more so than the average American.

The family names of the young soldiers who appear, including these three, are all Japanese names, such as Hayashi, Imamura, Matsuda, Ito, and Nishizawa. There is a passage about a comrade who nearly died on the battlefield: "As he was dying, he was quietly calling out to his mother in Japanese, 'Okaasan, Okaasan, Okaasan.'"

They fought bravely, made sacrifices to survive, and were honored by their country, but when the war ended and they tried to return home, discrimination did not disappear, and hardships continued even after the war. President Truman at the time said to the second generation soldiers who had achieved success in battle, "You not only fought the enemy, you fought prejudice, and you won. I want you to continue fighting. If you do, we will win." However, the fact is that the fight against prejudice was not a complete victory, so it was necessary to continue fighting.

On the other hand, there were also second-generation Japanese who fought against the American state. One of them was Gordon Hirabayashi, who, as a Quaker, opposed conscription on religious grounds and continued to protest against being drafted even though his family members had been interned.

The author, who has followed in Hirabayashi's footsteps, writes that the soldiers who fought on the battlefield, prepared to die, did so because they knew they were fighting for the loftiest ideals of America and the Western democracies, and that some young people, like Gordon Hirabayashi, "fought for their ideals in the courtroom."

He also believes that the fighting style that enabled second-generation Japanese soldiers to carry out their duties on the battlefield was due to the Japanese code of conduct known as "Bushido," as well as values such as "giri," "ninjo" (compulsory obligations), and "gaman" (endurance). He also believes that what Japanese Americans with both Japanese and American roots demonstrated on the battlefield reminded us that the American people are made up of diverse elements, including Japanese Americans, and are made up of diverse backgrounds and identities.

This book frequently depicts the battles with the German army, conveying the Japanese soldiers' emotional turmoil over the young German soldiers they killed and the German soldiers with families, as well as their feelings when they witnessed the brutality of the massacres and killings of the detained Jews.

The achievements of Japanese soldiers are worthy of praise. However, when we consider the enormous sacrifices they themselves made, we come to the conclusion that no matter how noble and just a fight is, it cannot be accepted if it involves sacrifice. Sacrifices usually start with the lower ranks of organizations and the weak, while those who advocate for a just cause stay at a distance and survive. This pattern is the same in today's wars.

There are many stories to ponder about: those who were inspired to fight, those who didn't want to fight but had no choice, those who fought despite having complicated circumstances, and those who survived or unfortunately died.

© 2025 Ryusuke Kawai