A rare community that preserves Japanese traditions

San Jose, California, is known as one of the few places where Japanese people who emigrated overseas have left their Japanese traditions and culture behind, and have maintained a unique Japanese culture. A special exhibition titled “San Jose Japantown: Inheriting the Thoughts and Spirits of Immigrants,” about the Japantown that formed in this city, which is located at the base of Silicon Valley, a hub of cutting-edge technology, is being held at the JICA Yokohama Overseas Migration Museum in Naka Ward, Yokohama, and is attracting attention.

"There are many Japantowns established by Japanese people overseas, but San Jose's Japantown is a rare example of how the culture and history of Japanese immigrants has been preserved through the efforts of the community," says Shigeru Kojima, a curatorial researcher at the museum.

The special exhibit traces the origins of San Jose Japantown and how it has survived through the war, and introduces Japanese stores and businesses that still exist today. Some of these stores have been run by the same family for generations, such as Ogura Shoten, which was founded in 1928 and now sells Japanese gift items and other products related to Japanese culture, while others, such as Shueido Japanese Confectionery, which was founded in 1953, continue to make Japanese confectionery despite changes in management, showing how "Japanese" stores continue to exist in various forms.

The program also highlights the roles played by elderly welfare organizations and Buddhist churches that have emerged from the solidarity of the Japanese community, and in terms of the preservation of Japanese culture and customs, a video is presented showing the OBON Festival, which is held every July and combines Bon Odori dancing with a Western-style carnival.

Many Japanese companies have set up shop in Silicon Valley, which is close to the city of San Jose, and many Japanese people are familiar with San Jose. Some of these Japanese people who have previously been stationed in the United States also came to see the exhibit. One elderly man looked nostalgically at the photos of Japanese stores and said, "I used to walk around San Jose a lot. There are some places that still feel more Japanese than Japan."

Surviving because of small size

According to explanations from exhibits, the first immigrants to this area were Japanese men who came to work on plantations in the Santa Clara Plains near San Jose in the 1890s. At that time, many Chinese people had already settled in San Jose, forming a Chinatown, and Japanese people began to gather there and formed Japantown, adjacent to the city.

Later, Japanese women began to arrive through picture weddings, second-generation Japanese children were born, Japanese shops were opened, a Japanese association was formed, and the community became more cohesive.

Before World War II, there were 46 towns called "Japantowns" in California alone. However, as a result of the war between Japan and the United States, Japanese and Japanese-Americans were forced to live in internment camps, leading to the collapse of communities, the loss of property, and the disappearance of many Japantowns.

Currently, only three cities in California have "Japantowns" remaining: Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Jose. Of these, San Jose is said to be the city that retains the strongest traces of immigrant culture.

While other Japantowns mostly disappeared during the war, there is a reason why San Jose's Japantown survived. During the war, San Jose's Japantown also became a ghost town, and Filipino and African residents began to live there. However, Japanese real estate was saved thanks to an American.

Due to California's Japanese Exclusion Law, Japanese people were not allowed to own land in their own name, and after being evicted during internment, they lost the basis for their livelihood. At that time in San Jose, American lawyer James Benjamin Peckham took custody of Japanese land in his own name, and when the second generation (with American citizenship) born in America came of age, he returned the land to the original owners, and in some cases rented the property to third parties, later giving the profits back to the Japanese people.

Mr. Peckham, who also held the title of "Legal Counsel to the Japanese Association," was later introduced as the "guardian of Japantown."

After the war, many of those who returned to San Jose from the internment camps but lost their homes started anew, living in hostels run by the San Jose Buddhist Church (Jodo Shinshu Honganji-ha San Jose Betsuin) or the Methodist Church. As more Japanese people were resettled, the number of Japanese businesses increased, and the Japanese town was more lively than ever from the 1950s to the 1960s.

Japantown gradually declined in the 1970s, but a growing awareness of the need to protect third-generation Japanese culture led to a rebirth in a new form. While this redevelopment in Los Angeles and San Francisco was driven by outside capital, in San Jose it was driven by small businesses, including family-run businesses, which actually helped to bring the community together.

Bilingual Mr. Sera gives a lecture

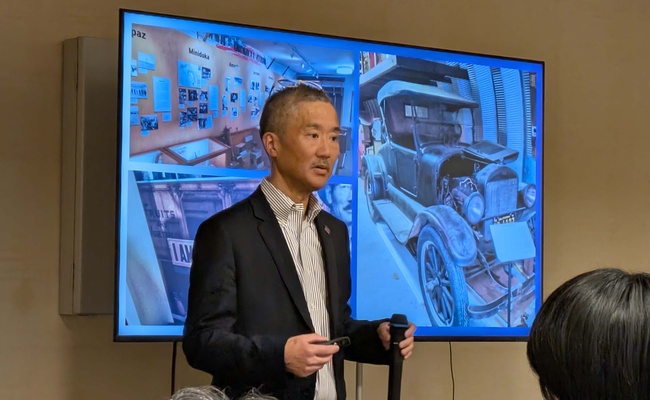

San Jose is home to the Japanese American Museum of San Jose (JAMsj), and in conjunction with this project, a public lecture entitled "The Importance of Japantown" was held on March 22nd by the museum's former director, Michael M. Sera.

Sera, a San Francisco native, began volunteering as a guide at the museum in 2010 and has since been spreading knowledge about Japanese American history.

As the venue was full, showing the high level of interest, Mr. Sera spoke in witty Japanese, explaining that the significance of Japantown is to pass on the history and culture of Japanese people in the area. He also said that the reason why Japantown in San Jose has survived for 135 years is because "it was lucky that the land was owned by a (Japanese) individual."

He also touched on the issue of the internment of Japanese Americans during the war, sounding a warning that "if we don't preserve history, the same thing will happen again." Finally, as a future issue, he stressed the importance of passing it on to the next generation, saying, "We can't maintain this Japanese town unless we sow the seeds in the hands of young people."

* * * * *

[Special Exhibition] San Jose Japantown: The Passion of Immigrants' Spirit and Spirit

Location: JICA Yokohama Overseas Migration Museum

Until Sunday, June 29, 2025

This exhibition traces the history of San Jose Japantown and introduces the cultural heritage left behind by immigrants through the activities of the Japanese people living there, various organizations and stores, and how it has been passed down to the present day , using various documents, photographs, interviews, and testimonials.

© 2025 Ryusuke Kawai