Similarities with the internment of Japanese Americans

Just as there were facilities in the United States, Canada and Australia that forcibly interned citizens of the enemy country, Japan, too, had similar facilities for people from enemy countries during World War II.

Although it is not widely known, one of these was the concentration camp for Italians in Nagoya. Italy was an ally of Japan along with Germany, as seen in the Tripartite Pact, so some may wonder why Italians were interned there.

I was one of them, but if you look closely at history, you can see the situation. Of the three countries, Italy surrendered to the Allied forces in September 1943, but the Fascist Republic of Salo (Italian Social Republic) was established in Salo, northern Italy, as a puppet government of Nazi Germany. Japan recognized this government, and considered Italians living in Japan who did not recognize this government to be enemy aliens, sending them to concentration camps in Tenpaku Ward, Nagoya (then Tenpaku Village).

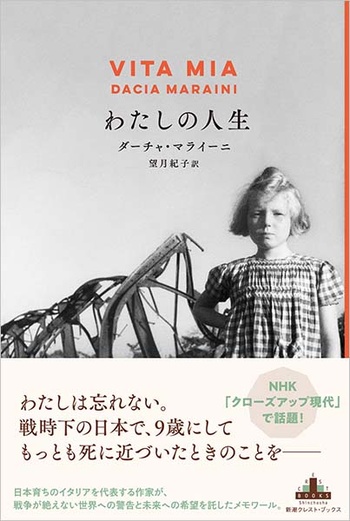

Among them was a girl who would soon be seven years old at the time. This was Dacia Maraini, who would later become a successful author, poet, and playwright. The Japanese version of her novel "VITA MIA," which she wrote after a long silence, was published last fall by Shinchosha, translated by Noriko Mochizuki.

First she says:

"Confronting this painful subject for me (Japan and Japanese concentration camps) has been very difficult. I have touched on it in some books but never really faced the details of my days in internment and how they marked my life. Now I feel I must confront it, overcoming the shame and shyness I know I share with many other former internees."

It is often said that many Japanese Americans who lived in internment camps in the United States during the war were reluctant to talk about their experiences for a long time after the war. In the same way, the author has instinctively felt that it would be better to keep the painful and humiliating experience of internment locked away in a corner of his heart. However, at the same time, voices calling for the story to be told also seem to have arisen.

The girl was so hungry that she even ate ants

Dacia Maraini, born in 1936, came to Japan in 1938 with her father, Fosco Maraini, and mother, Topazia Arriata. Her father, Fosco, had a strong interest in Asian and Japanese culture, and began studying Ainu culture at Hokkaido Imperial University. He later moved to Kyoto and worked as an Italian language instructor.

During this time, Dacha's younger brother and sister were born in Japan, and the family of five assimilated into Japanese culture, with Dacha becoming accustomed to the Kyoto dialect and leading a peaceful life. However, in 1943, with the establishment of the Republic of Salo, the family was sent to a concentration camp. When the war ended with Japan's defeat, the family was released and eventually returned safely to Italy.

"My Life" is the author's recollection of his experiences in the internment camps from the time he came to Japan until he left, and at the same time contains deep reflections on human life and death, cruelty, and Japanese culture that are inseparable from his experiences.

Let's follow her recollections. In September 1943, my father and mother were suddenly called by the police and asked whether they would swear allegiance to the Italian fascist regime (the Republic of Salò) that Japan recognized. It was like a question of whether they would renounce their loyalty to Japan in the Japanese-American internment camps in the United States. Both my father and mother refused, because it would mean accepting Nazi Germany and racial prejudice.

As a result, the police branded them "traitors to their own country" and treated the family as enemy aliens. After three weeks of house arrest, the whole family was sent to an internment camp in Nagoya. At first, they were told to leave their children in an orphanage, but they insisted on taking them with them. The orphanage was later bombed and all the children died.

The family was taken by truck with only one suitcase by the overbearing police officers who treated them like criminals to a two-story camp surrounded by barbed wire, where 16 people were crammed into three rooms. The sanitary conditions were poor, it was cold, and the food was inadequate. The Japanese government distributed food to the camp, but the police officers on guard concealed it.

They were plagued by fleas and lice, and were exhausted from malnutrition and lack of sleep, developed beriberi, nosebleeds, swollen feet, and hair loss. The police looked on without a care in the world. They skinned a snake they caught near the camp, roasted it and ate it, their mother tried to see if they could eat grass and flowers, and Dacha was so hungry that he picked up ants and ate them, which caused him to get an upset stomach.

The only times they were given enough food were when there were inspections by people from the Red Cross or other outsiders. The police officers tried to disguise their treatment. Despite the harsh conditions, the Italians in the camp managed to get by through negotiations, but as they grew physically exhausted, the atmosphere became tense.

As the war situation worsened for Japan, Nagoya was hit by air raids and then suffered damage from an earthquake, so the internees were moved to a temple in what is now Toyota City.

Living in the temple surrounded by nature gave the family peace of mind. The family of the head priest of the temple who lived nearby was kind, and Dacha became friends with the temple's granddaughter. They began to interact with the Japanese farming family in the area, and the surveillance became laxer. Eventually, the police fled, and the prisoners were released after the war ended. U.S. military planes flew overhead and dropped food to the prisoners. What controlled Japanese society was changing.

The shrewd policeman fled, and the policeman who had said, "When we win the war, I'll slit your throats," came to the family, begging for supplies, pleading for mercy. Dacha gave chocolates to the Japanese friends and family who had looked after her. "The farmers' attitude was very good," she says, because instead of begging, they offered to trade rice for canned food.

"Japanese girl"

After this, the family went to Tokyo and then boarded an American ship to return to Sicily, Italy. Although it was the family's hometown, for Dacia, who had lived in Japan for as long as she could remember, life in Italy was like jumping into unknown waters.

"I saw myself as a Japanese girl who had come to Italy to learn about her family's past and shape its future, but who knew very little about the customs and habits of her home country."

Having spent seven years as a child in Japan, Dacia became completely accustomed to Japanese culture and naturally came to identify as a "Japanese girl" who spoke Kyoto dialect, rather than as an Italian. In other words, she became "Japanese." But when she was put in an internment camp, and her family and other Italians were treated with hostility and discriminated against, she became aware of her Italian identity and began to have complicated feelings.

Problems arising from this dual identity were also aroused among the Japanese Americans who were interned in the United States at the same time. They were struggling with inner conflicts, while at the same time facing friction between their own identities and the state that forced them to take a certain position.

Returning to the story of Dacha, as a Japanese girl, she must have had many complex emotions, such as anger and bitterness, swirling around for many years at the way she was treated by Japan. However, despite the brutal treatment she endured in the concentration camps, she looked at people and culture, not race or nation. Rather than condemning the country or its people, I feel a sense of empathy for Dacha Maraini's words, which question the roots of evil and injustice.

The translator of this book published "Daca and Japanese Concentration Camps" (Miraisha) in 2015. Also, in 2016, Mooja Maraini Melehi, Daca's sister and the daughter of writer Toni Mailani, released a documentary called "Haiku of the Plum Tree" (music by Ryuichi Sakamoto) that traces the footsteps of the family's internment.

© 2025 Ryusuke Kawai