Beacon Hill, or Queen Anne hill. Except a knoll is a small hill, probably one that is a lot smaller than those two well-known Seattle landmarks. But whatever that hill is, it’s called Mary? “Mary Knoll?”

Well, no. Maryknoll is not the name of a local hill. It has nothing to do with everyday geography, except to note that the priests and nuns of the Maryknoll Catholic Order are in all parts of the world wherever people are. It’s part of the Catholic orders and societies involved in worldwide missions that assist in everyday life; in doing so, they spread the beliefs of the Catholic religion.

My experience with the Maryknoll society, all takes place in Seattle, before and shortly after World War II, the war between Japan and the United States.

Before WWII, the Tokita family, consisting of my father, Kamekichi, my mother, Haruko, and five children, lived at the Cadillac Hotel1, located on Jackson Street between Occidental Avenue and 2nd Avenue South. The children, sons Shokichi (me), Yasuo, and Yuzo, and daughters Shizuko and Yoshiko lived there, on the southern edge of downtown Seattle bordering Chinatown.

There were absolutely no other families with children “within reach” where we lived. So, our playground was the sidewalk around the block. With no families within a short walk of where we lived, we had no playmates except ourselves.

When I reached school age, around four years old, my parents started thinking about where I should go. My mother came to the U.S. when she was 12, and attended Bailey Gatzert Grade School, located at 12th and Lane (site of today’s Seattle Indian Health Board), which was a possibility. A search found that there were no other grade schools closer than Bailey Gatzert, but that meant a walk up Jackson to 12th Avenue, then three blocks south to Lane Street. That amounted to a 12-block walk through some heavy vehicle-traffic areas. Street traffic was more than intolerable for a child, especially around Third to Sixth Avenues near the train station. So, that was quite a dilemma.

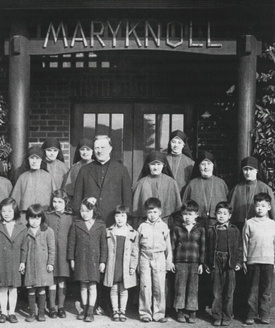

After some research, Papa found that Maryknoll Grade School, located at 16th and Jefferson, had a bus that picked up children around the Chinatown area which became another possibility. Needless to say, a Maryknoll bus pickup was the absolute solution to the “walk to school” dilemma; so I started first grade at Maryknoll in or around the fall of 1938.

Starting school there consisted of catching the bus in front of the Cadillac Hotel, riding through the downtown area, primarily in front of other hotels to pick up other kids, then north and east. A turn north onto 16th for half-a-block allowed us to get off close to the Matsudaira residence. From there, we all “poured into” Maryknoll Grade School. And, that was the start of my grade school “career.”

What was it like at school? Primarily, it consisted of nuns who were dressed in black from their shoulders to their ankles, and in headpieces that were pointed together at the front, like the front of a boat. The headpieces were topped with a veil that went from the top and back of the nuns’ heads down to the middle of their backs. They were addressed as “Sister Magdalen” or other female saint’s names, but always preceded with “Sister. …”

Classes were held from morning till 2:00 PM. They were followed by Japanese classes taught by lay teachers who were Japanese women, till 4:00 PM. “Katakana,” beginning Japanese writing, is what I remember of the latter classes.

Eventually, we found out that the head of the local Maryknoll Order was a priest named Father Tibesar.2 He was a tall jocular man who seemed to have the overall respect of everyone associated with Maryknoll School. One of the really interesting things about Father Tibesar was the fact that he had lived in Japan for ten to twelve years and spoke Japanese fluently.

As a result, he always gained the respect and admiration of the Issei in the local area who had anything to do with the school and the congregation which developed around the Maryknoll parish. These Issei included Papa, who looked up to him.

When WWII broke out between Japan and America in December 1941, our home was thrust into turmoil. Mama and Papa discussed whatever needed to be done as news about our fate came down irregularly. Finally, we were advised that we were being thrust into a concentration camp, first in Puyallup. Later, after a period of time, we found ourselves in tarpaper barracks in southern Idaho, at Minidoka, near Twin Falls, Idaho. This camp, like the one in Puyallup, had barbed wire fencing and army-manned guard towers with weapons facing inward towards us!

Guess who joined us in these concentration camps? Father Tibesar! He continued serving the religious rites of the Catholic religion to the Japanese Catholics in camp and assisted in numerous other ways for several years.

When the war’s end was imminent, and the U.S. was safe from any potential damage, Father Tibesar returned to Seattle and helped returning Japanese get resettled. That was when Papa contacted him and requested his aid.

Father Tibesar met us at the train station when we returned to Seattle. He had found us a place to live in the former Japanese Language School, “Koguko Gako” or “Tip School,” located at 14th and Weller. It is now the Japanese Cultural & Community Center of Washington (JCCCW).

A few days later, he picked up four of our family’s grade-school children and delivered them to St. Mary’s Grade School, at 20th and Weller, where incidentally, all eight Tokita children eventually finished grade school! Then he picked up Kamekichi and took him to St. Vincent De Paul, which was located at Lake Union, where he started employment as a sign painter!

That is how Father Tibesar, the Maryknoll priest who epitomized the historicity of the Maryknoll Catholic religion, helped the Tokita family, then with seven children, to settle in immediately and restart life after WWII. All of his assistance was an actual gift from heaven in the fall of 1945!

Note:

1. A story about Shox and his family when they lived in Cadillac Hotel: “Tokita Tales—Family Protocols”.

2. To learn more about Father Tibesar, read “Father Leopold Tibesar – The Shepherd of Seattle” by Jonathan van Harmelen.

© 2023 Shokichi "Shox" Tokita