Medical technologist Pedro Ruiz's relationship with the Nikkei community began in 1980, when he was eleven years old and his father enrolled him in La Unión school.

The seed, however, was planted several decades ago, when his father was studying at Guadalupe School and made Nisei friends.

Later, during his studies at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of San Marcos, he made friends with students of Japanese origin.

Time progressed, young people graduated as doctors and his Nikkei friends invited him to participate in the health campaigns that were held annually in La Unión.

His father liked the school's infrastructure. Furthermore, his friendly ties with Nikkei, cultivated since childhood, fueled his interest in Japanese culture. He even studied a little Japanese on his own from a book.

Thus, she decided to put her two sons in La Unión. The oldest of them, Pedro, was worried about something in particular: how was he going to understand the classes if he didn't know Japanese?

BETWEEN ENRYO AND RICE WITH GUTTA-PERCHA

Pedro discovered with relief that classes were taught in Spanish. Now, there was a nihongo course, so before entering school he studied the basics at the Peruvian Japanese Cultural Center (CCPJ) to try to be on par with his future classmates.

It was not easy to deal with the new language. At first he had trouble pronouncing surnames, like Higuchi, for example, which he said ignoring the “h” (dumb in Spanish), which was a source of general hesitation. He had to learn that the “h” is pronounced like the “j.”

However, by the middle of the year he had already made a move with the nihongo ; At the end of the period, he was on track like the others.

That said, what surprised him most was not the language, but that when the teacher asked a question in class, if he knew the answer, he would raise his hand to respond. The others didn't usually do it.

Others refrained from raising their hands, even knowing what to answer, due to a certain modesty characteristic of the Nikkei.

“It's not that I was the only one who knew, but that there was a certain enryo . That's what caught my attention, that people kept a little to themselves," he says.

It was also difficult for him to get used to the food. He mentions makizushi , which his classmates jokingly called “rice with gutta-percha” and which was offered at events such as undokai.

Pedro fit well in the room he was assigned to. He never suffered discrimination or anything like that for not having Japanese ancestors.

THE WAND TO GROW RIGHT

In the Nikkei community, people talk day in and day out about the values, the principles that the Issei bequeathed to their descendants. It was not like this in the past. They were simply practiced, there was no need to talk about it because it was as natural as a ray of sunshine in summer.

Nobody took what was not theirs. You left a backpack or whatever, you came back hours later and found it in exactly the same place. No one boasted about honesty because it was an ordinary practice. Pedro remembers those times:

“They never told us 'you have to be like this, you have to be like that'. Nobody told us 'give back what you find', 'don't steal'. You could find 10 cents and give it to the regent. It was normal".

“We finished studying at 3 in the afternoon and we all left our things in the parking lot; There is a little wall on the wall that borders the school. Everyone left their things there. Then I would go to the band, the scouts, (the school magazine) Punto Apart or something else. I was staying late. When I returned, I found my suitcase alone there, not even here that anyone could take it,” he adds.

“Was there a little sign that said: 'No touching'? No. These are things you lived with and were normal,” he emphasizes.

When he graduated from Union, he discovered that what he thought was normal was not normal in other schools.

He once visited a school and noticed, with perplexity, that at recess time the students left the classrooms to the playground with their backpacks. “Why?” he asked. “Because things can be stolen,” they responded.

The Union was fundamental in his moral formation. It covered his transition from childhood to adolescence.

“I am very grateful to La Unión for that. When the trees start to grow, don't they sometimes put a wand on them to make them grow straight?” he asks. “It was my wand, because I had everything there,” he says about his school.

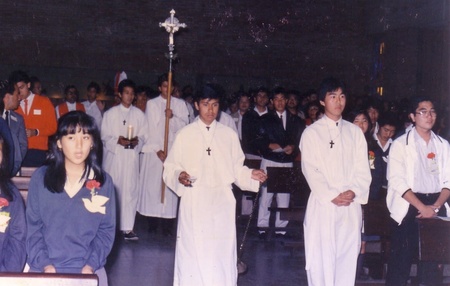

In addition, it helped to germinate in him the spirit of service to others through the scout movement and strengthened his Catholic faith. There he was confirmed and later became part of Unión en Cristo, a group of young Unioninos who catechized children for their first communion.

From his Union period he remembers with gratitude and affection the professors Pompilio Ramírez (also director), Felipe Tapia, Marta Páez and Juana Goto.

He integrated so much that, once, during a conversation among colleagues, someone said “el perujin …”, referring in an unfavorable way to a Peruvian of no Japanese origin. Pedro immediately jumped in: “I am Perujin .” “Nooo, you are like us,” they told him. They considered him just another Nikkei.

PERU SHIMPO AND THE KIMOCHI

Pedro's ties with the Nikkei community widened in the 1990s when he joined the Spanish editorial team of the newspaper Perú Shimpo .

He did not look for it or plan it, because his mind was on his university studies.

As the journalist Ciria Chauca knew him from his school days and had even interviewed him, she called him to act as coordinator of correspondent students of the Nikkei schools La Unión, La Victoria, José Gálvez and Hideyo Noguchi.

The students of these schools found in Perú Shimpo a space to make their voices heard.

This work allowed him to meet people whose human quality stands out to this day, such as Pedro Maeireizo, Juana Miyashiro and María Benavides, directors of José Gálvez, Hideyo Noguchi and La Victoria, respectively.

It was a very rewarding experience for him. “My connection with the schools was very nice,” he remembers.

Now, Peru Shimpo would be just a stop. At least that's what I thought. However, little by little they began to ask him for more things (collect data on this activity at the CCPJ, take this little camera and take photos, etc.) and so, without imagining it, he stayed for ten years.

The most intense experience he lived as a journalist was the capture of the residence of the Japanese ambassador in Lima by a terrorist movement in December 1996 and the military rescue of the hostages in April 1997.

He went almost daily to the residence to cover the news. If he wasn't there, I kept an eye on the radio just in case.

He remembers being at the movies one day, with one ear to the radio, when he heard that there would probably be a hostage release around Christmas and went to the residence.

Perú Shimpo was used to closing the edition at 6 or 7 at night, but sometimes it had to be redone hours later if there was any news regarding the hostages.

Until the day of liberation arrived. Like the day of the capture, it all started with some explosions. He found out on television and flew out of his house. A taxi left him near the place.

“Everything was 'bang, bang!', it really seemed like a war. And me running. 'Stop, stop!' the police yelled at me. I showed my (journalist) credential. Until I got there. There was speculation: 'The terrorists are blowing up everyone'; 'No, it's the military.'” There was still uncertainty.

Suddenly the noises of the detonations fade away and “screams of triumph are heard. They begin to tell us: 'They (the hostages) have been released!' Until the first bus of the liberated leaves. We all felt joy because people came out happy, all shouting 'long live Peru!'"

The coverage of the hostage crisis captured, he says, the spirit of Peru Shimpo . It was not just a matter of informing, of disseminating data, but of reaching readers, of reaching them, of people who had relatives or close friends within their residence.

“It was not a cold writing, but with body and soul. We had to add that extra, that they knew that we were there, that Perú Shimpo was there, that it was accompanying them,” he comments.

Therefore, the experience was “far beyond just journalism, I had a kimochi , a very special thing.”

Generally speaking, he gives as an example of the closeness between the newspaper and its users, of an emotional and deep relationship with the Nikkei community that far transcends the journalist-reader bond, Ciria Chauca (with almost 40 years in Peru Shimpo ) and Mario Teves (more than half a century in the newspaper).

Peru Shimpo became like a family to him. That's why he stayed longer than he had planned. He had already completed his studies and was ready to pursue his career, but he decided to continue, first, for the centenary of Japanese immigration in 1999, and then for the 50th anniversary of the newspaper in 2000. “My feeling with Perú Shimpo is one of gratitude. “How do you leave your family when they need you?” he says.

Here we return to what he said about the values that were not taught or preached, but rather practiced in La Unión: “Those are the things that you learn from the Peruvian-Japanese community. Nobody teaches you, nobody tells you 'you have to be'; You see those experiences, that sharing, and you attract them to yourself and you start doing that.”

Incidentally, during his time in Peru Shimpo had the opportunity to travel to Japan to accompany members of the Hideyo Noguchi school to a folk music festival in Fukushima ken.

In Japan he had an experience that he shares with laughter. He was with the Japanese who welcomed him when he said “jidosha” to refer to a car. Everyone burst into laughter. He didn't understand why, until they explained to him that it was no longer called that way, but rather "kuruma."

Those types of experiences that only a Nikkei could understand bring him closer to a community that has given him—especially the school—some of his best friends.

Almost 40 years have passed since he left La Unión, but he still remembers the complete, alphabetical list of the surnames of his classmates. And to show that he is not selling smoke he begins to recite:

“Amemiya, Aragaki, Chinen, Chumo, García, Goya, Guima, Harada, Heshiki, Higa, Higashionna, Higuchi, Inafuku, Kamisato, Kanashiro, Kitayama, Kitsutani, Maehira, Miyasato, Moromisato, Muñoz, Nakamoto, Nishimura, Noriega, Ruiz , Seragaki, Shimura, Shirakawa, Tamashiro, Tanaka, Tomioka, Tsunami, Yamasato, Yara, Ygari, Ynouye, Yrei.”

*PHOTOS: personal archive.

© 2024 Enrique Higa Sakuda