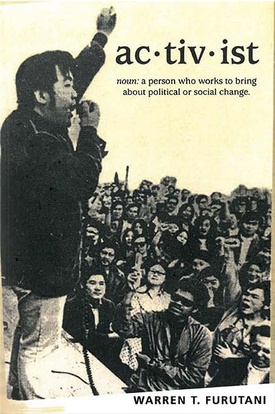

With the publication of the memoir ac•tiv•ist, Warren T. Furutani has proven that he can wield the power of the pen, just as easily as he can persuade you with his gift of gab.

Readers can follow the evolution of Furutani from a young, wide-eyed idealist to the seasoned politician, who comes to realize he needs to compromise if he wanted to get anything done.

Along the way, Furutani offers sage advice, especially to community activists thinking about effecting change from within the system rather than as an outsider making demands. His insights into what he learned from his failures and how to take advantage of victories are priceless.

Furutani made history back in the 1980s, when he became the first Asian Pacific American elected to the Los Angeles Unified School District Board of Education and then served as the board’s president. From there, he served on the Los Angeles Community College District Board as a trustee and later as president, then went on to the California State Assembly (2008 to 2012).

But before Furutani worked for the establishment, he was a grassroots activist, organizing from the outside. He was part of the wave of Asian Pacific Americans who came of age during the turbulent 1960s and 1970s when African Americans were battling for civil rights, and youths across the nation were protesting America’s involvement in Vietnam.

Furutani graduated from Gardena High in 1965, and then he made his way to Northern California, to the College of San Mateo, where he found his “voice,” his calling and met his first wife, Rhoda Woo. At San Mateo College, he also got arrested for participating to incite a riot.

Furutani’s involvement in the December 1968 campus melee, which preceded the larger, more widely known Third World Student Strikes at San Francisco State University and UC Berkeley, brought him notoriety. He would go on to be invited as a speaker at a number of protest rallies, including at S.F. State.

Furutani eventually returned to Southern California and became involved in a wide variety of community activities from writing for the Gidra newspaper and supporting Yellow Brotherhood to working for the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL).

Part of Furutani’s JACL work involved meeting with Japanese American farmers during the height of the United Farm Workers movement. It would be a humbling and educational experience for Furutani.

As a JACL staff member, Furutani also met with Nikkei leaders in New York City. It was here that he met his future second wife, Lisa Abe, and his future mother-in-law, Aiko Herzig Yoshinaga.

After the United Farm Workers had marched from Delano to Sacramento and the African American community had had their March on Washington, Furutani and Victor Shibata sought an issue that Asian Pacific Americans could rally around. This was the beginning of the first organized group pilgrimage to the Manzanar War Relocation Authority camp. The two would later learn that Rev. Sentoku Mayeda and Rev. Shoichi Henry Wakahiro had been making annual pilgrimages to Manzanar to pray for the dead since the closing of that camp.

A year later in 1970, Furutani co-founded the Manzanar Committee with former Manzanar incarceree Sue Kunitomi Embrey. Five decades later, the Manzanar Committee continues to carry on its mission.

Not surprisingly, the solidarity movement among people of color gained the attention of the U.S. government, which started to infiltrate community organizations with agent provocateurs, causing division and infighting among the groups. Furutani would then refocus his energies into working within the system and decided to run for elected office.

But whatever seat Furutani occupied, he never lost sight of the importance of sponsoring and passing legislation related to education. Within the Nikkei community, Furutani is most known for pushing the LAUSD to award high school diplomas to Nisei who could not participate in their graduation ceremonies due to their unconstitutional incarceration during World War II. This included his mother-in-law, Herzig Yoshinaga.

Later in the State Assembly, Furutani sponsored Assembly Bill 37, which granted honorary college diplomas to deserving Nisei, and AB 1775, which established Jan. 30 as Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution in California.

The memoir, overall, is a good read and well written but it could have used one last copy-editing run. One of the funniest typos is when Furutani discusses the ingredients that can go into menudo. He notes that “you can spike it with Mexican oregano, chopped cilantro, diced union…” Diced union? Must be a Freudian slip.

And like other American-born Japanese, whose knowledge of the Japanese language is limited or non-existent, the memoir has Japanese words that are phonetically misspelled. Best to have a Japanese native look those over.

And while Furutani has a touching tribute to his sons and wife in the last segment of his memoir, readers might get confused during the middle of the book when Furutani writes early on that he and Rhoda Woo had an amicable divorce, then he teases readers about meeting Lisa Abe and a few chapters later, Furutani and Abe already have two sons. — Wait? What? When did Furutani and Abe get married?

Another point is how Furutani handled the murder that occurred at the 1970 JACL National Convention in Chicago. He writes about the incident briefly, noting that the “momentum for change was abruptly stopped in its tracks” due to the murder.

Most readers will probably want to know if the killer had ever been caught (no); who was the victim (Evelyn Okubo); and the survivor (Ranko Carol Yamada). Yamada would go on to play a huge role in the Chol Soo Lee case but is not mentioned in Furutani’s short segment on the Free Chol Soo Lee movement.

Additionally, since Furutani interacted with so many historical people (i.e., Jack and Aiko Herzig, Mary Nakahara (aka Yuri Kochiyama), Tak and Kaz Iijima, Mervyn Dymally, to name a few), the book could have considered including an addendum with a brief biography on these earlier-era activists, whose names might not be as familiar to the younger generation.

It is worth noting that Furutani published the memoir in Furutani fashion — he didn’t go through an established publisher. He self-published it and the book can be purchased for $21 at www.ac-tiv-ist.com.

* * * * *

The Rafu Shimpo Editor’s note: This article is the final submission by Martha Nakagawa, who passed away on July 28 at the age of 56. She was a staff member of The Rafu Shimpo in the 1990s and continued to contribute news articles and opinion pieces after that. She will be remembered as an outspoken advocate for the Japanese American community, particularly for those whose stories were not widely known.

*This article was originally pusblished in The Rafu Shimpo on August 6, 2023.

© 2023 Martha Nakagawa