I knew that there had been Japanese people going to Australia to collect white pearl oysters (commonly known as pearl oysters) since the Meiji period, but while traveling along the coastline of the Kii Peninsula from Mie Prefecture, I happened to hear from someone who told me that his grandfather had been one of those people.

There used to be a shipyard called Kyoryoku Shipyard in Ise City, Mie Prefecture. In the summer of 1956, a deep-sea tuna fishing boat was converted here into a training ship for the Tokyo University of Fisheries. The boat was the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, which encountered an American hydrogen bomb test near Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean on March 1, 1954, and was covered in "fallout" (radioactive material).

During an interview to trace the history of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, I had the opportunity to talk to Osamu Goriki, the third-generation president of the former Goriki Shipyard, and since then, whenever I go to Ise, I visit Goriki and he tells me stories of the past. When I visited Goriki again this time and we talked about the sea and ships, he told me that Goriki Shipyard had once been commissioned to build a ship that went to Australia to harvest pearl oysters, and that the grandson of that client runs a store that deals in pearls in Shima City.

"If you're interested, I can introduce you," he said, so the next day I went to visit Nakamura Shigeru, who runs the pearl shop "Arafuramaru Shokai" near Cape Daiozaki, which juts out into the sea.

The pearl oysters in Australia were harvested in the Arafura Sea between Australia and Papua New Guinea, and inside the store there are many photographs showing the boats that Nakamura's grandfather, Toshiro Nakamura, used to harvest the oysters, as well as photographs of the local area.

Shell buttons made by hollowing out pearl oysters were treated as expensive products due to their unique luster and texture, and people from Japan began to go out to collect them from the early Meiji period. According to Shigeru, Toshiro was invited by an acquaintance from his hometown who had already gone out, and he worked as the captain of a pearl-collecting ship in the area.

However, as he was employed by local people and his income was not that great, he decided to set out on his own boat, ordered a boat from Kyoritsu Shipyards around 1931 or 1932, and embarked on a business of collecting shellfish himself. "My grandfather was a captain, but apparently the job of a diver who dives to collect shellfish was said to be the most dangerous occupation in the world," says Shigeru.

In addition to Toshiro-san, there were other people who went to collect pearl oysters from Mie Prefecture, such as the Shima Peninsula, but in this respect, the Kushimoto region of Wakayama Prefecture is the most famous, and many people went to Australia. I heard that this story is passed down as local history, and that there are exhibits of this history together with documents in the town.

After touring the Shima Peninsula, we planned to tour the coastline of the Kii Peninsula, and especially since Kushimoto is where the Lucky Dragon No. 5 was built, we decided to stop by.

The southernmost "exhibition hall" in Honshu

Leaving the Shima Peninsula behind, we head southwest, leaving Owase City as our last stop, then head south from Mie Prefecture into Wakayama Prefecture, and arrive at Kushimoto Town, located at the tip of the Kii Peninsula. Koza (formerly Koza Town) in Kushimoto Town is where the Daigo Fukuryu Maru was built. When I visited the area several times for interviews, I was assisted by Nakae Takamaru, a town council member who has been researching the history of the area in detail and has been involved in the peace movement.

I contacted Nakamoto again and told him that one of the reasons I visited Kushimoto was to research the history of pearl oyster diving in the area. He immediately took me to a place where the materials were on display. The place was a small, single-story building called "Southernmost Point of Honshu Sea Breeze Rest House 1 ," located in a corner of Cape Shionomisaki, which is said to be the southernmost point of Honshu that juts out into the sea.

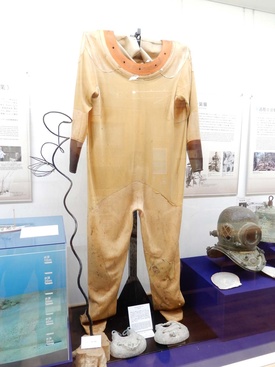

It is literally a rest area for tourists, but inside there is an explanation of the history of the people of Kushimoto who went to Australia in search of pearl oysters, and there are exhibits of photographs from that time and diving equipment that was actually used to collect the oysters.

Summarizing from the explanations and documents, the outline of the history is as follows:

Wakayama Prefecture, like Hiroshima Prefecture and others, is known as an "immigration prefecture" that produced many immigrants, but in the Kushimoto region, from the mid-Meiji period to the early Showa period, people traveled to a wide range of places, including Australia, Hawaii, North and South America, and the South Pacific, in search of work.

Australia was the first place to start, when in 1884 30 people responded to a recruitment ad to work in the pearl oyster harvesting industry, which was active in the Torres Strait in Queensland, in the north of Australia (160 km north to south, 220 km east to west).

In the Torres Strait, pearl oysters were first harvested by the British, who exported them to Britain as materials for luxury shell buttons and shell crafts, earning huge profits, and shell harvesting became popular. Thursday Island, a small island of 3.24 km2, was used as the base for this harvesting.

The first Japanese person to come to these waters to harvest pearl oysters was Nonami Kojiro from Shimane Prefecture in 1878. Queensland began accepting free immigrants without contracts around 1892. The Japanese population continued to increase, and by 1897 the number of Japanese on Thursday Island had exceeded 1,000, making up 60% of the population at one point. A Japanese town was also formed on the island.

A total of 7,000 Japanese worked on this project, 80% of whom were from Wakayama Prefecture. At first, Japanese people were just employed, but by the 1880s, Japanese people were able to own ships.

Among them, Torajiro Sato, from Takaike Village in the former Higashimuro District near Kushimoto Town, led young men from his town across to Thursday Island, where he launched a pearl oyster harvesting business with 2,000 divers, including young people from the Kiinan region of Wakayama Prefecture, and was nicknamed the "King of Thursday Island." However, due to the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 imposed by the Australian Federal Government, he was not allowed to own a boat unless he was naturalized, and was not allowed to go ashore except in special cases such as illness, so he was forced to live a life at sea.

The shellfish harvesting business continued into the Taisho and Showa eras, and the ships became larger and the area of operation expanded. However, there were constant accidents such as decompression sickness and shipwrecks, and about 700 Japanese lost their lives on Thursday Island alone. Of these, 162 were from Kushimoto Town.

When the Pacific War broke out in 1941, the Japanese on Thursday Island were interned by the Australian government and placed in internment camps in New South Wales on the mainland, which essentially put an end to the pearl fishing business in the Torres Strait, centered on Thursday Island.

A diver's ship attacked shortly after the start of the war

The above is an overview of pearl oyster harvesting by Japanese people, but there is something I would like to add in relation to the war. As soon as the war began, Japanese fishing boats were requisitioned for military use. There is a book called "Ordinary People's War and the Sea" (by Nakamura Ryuichiro, Toho Publishing) that compiles information about fishing boats and other small civilian boats that were requisitioned during the war in Wakayama Prefecture. While there are few documents that compile information about the requisition of fishing boats during the war, this is a valuable record that has been compiled including interviews with the people involved. It reveals some surprising facts about the requisitioned pearl oyster harvesting ships.

Two months before the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, Japanese divers who were supposed to be harvesting pearl oysters in the waters off Australia were forced to gather intelligence on the enemy while rigging dives. And on the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941, these Japanese divers came under heavy attack from enemy aircraft in the seas near New Guinea, burst into flames, and the fishermen from Kushimoto who were on duty there died.

The diver's ship was the one that was attacked in retaliation immediately after Japan raised the signal for the start of war.

Returning to the topic of the Japanese who went to Australia to harvest pearl oysters, some of the Japanese who were interned when the war began returned to Japan after the war, but after living in Australia for so long, some of them married local women, started families, and stayed there. Others had already put down roots in Australia before the war. From then until today, the history of Japanese people in Australia has probably been building up little by little.

Notes:

1. The Sea Breeze Rest Area and Kushimoto Town Library have materials and books related to pearl oyster fishing in Australia.

© 2023 Ryusuke Kawai