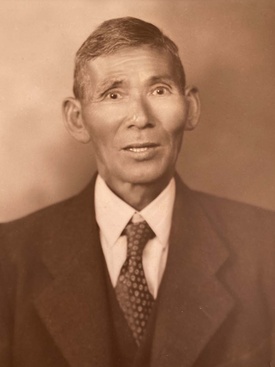

Tomo, my grandfather

My grandfather Tom (Tomo) was a joker, the self-confessed black sheep of the family. He liked to “stir the pot,” and his deep belly laugh would erupt whenever he sensed some kind of family controversy.

Just for fun, he left my grandmother waiting at St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Sydney on their wedding day “FOR A LONG TIME” (she said) for him to arrive. She wanted to strangle him. He just laughed.

I called him Pop. He was strong-willed, bullish, hard-working but also very charismatic and well-liked. He seemed to have inherited his confidence from his Australian mother, Annie, who drove an ambulance during the war and, in her later years, chauffeured a wealthy man across the Nullarbor desert, only to have him die of a heart attack halfway. She kept driving with his corpse until she reached the next town.

Pop’s Japanese father, on the other hand, was polite and softly spoken. Shojiro always tipped his hat to the ladies. He worked hard and liked to gamble. Pop said he learnt to wash and cook rice from his father. Pop was famous for his fusion fried rice that included tinned tuna and became a family tradition.

Pop and I shared an interest in three things: our family history, traveling, and blackberry jam—our favorite flavor.

In my childhood and university days, I regularly visited my grandparents’ modest home near Parramatta in the suburbs of Sydney, where my mother and her siblings grew up. We’d chat at the kitchen table, sitting on retro, purple swivel chairs. Pop was very good at telling me the facts: names and dates, that sort of thing. But I desperately wanted to know about moments, conversations, and people.

Before Pop died in 2018, he left me with the most precious of gifts: his old photos, birth and death certificates, contracts, newspaper clippings, and much more from his years of collecting and research into our family tree.

Since he passed, a whole new tranche of information about our family has been released at the National Archives of Australia. I only wish he could have seen all that I’ve unearthed.

To Pop,

I now understand how hard it was for you and your family in Australia during WW2 and postwar. I wish I had that insight before you died.

I know this is why you left all your research to me. You knew I would continue to explore our history and treat all this knowledge with care. So here I go, trying to tell your story as best as I can.

Shey

Piecing together the past

My great-grandfather Shojiro Omaye was born in Kainan, Wakayama in 1880. At 22 years old he boarded the Kumano Maru in Yokohama with 76 other Japanese workers bound for Townsville in northern Australia. He was contracted to work on the Pioneer sugar cane plantation for four years.

Although the conditions on the cane fields were reported to be quite good, for some reason Shojiro absconded a few months in. He was caught and either fined 3 pounds 4 shillings or received three months’ imprisonment, I’m not sure which.

I know nothing about Shojiro from 1902 until 1914, when I finally found a record of him working in a laundry in Brisbane. He ended up owning two laundries in Sydney by the 1930s.

Shojiro met his wife, Annie, while doing gardening work at a school (Shojiro’s father, Seyomon, had also been a gardener in Japan). Annie was a teacher at the school. She had grown up on farm in Inverell, in northern New South Wales. Shojiro and Annie were married in 1918 and had five children: Aya (born in 2018), Yuki (1921), Kazu (1923), Tomo (my grandfather, born 1925) and Kiyo (1926). I love that each child was given a Japanese name, although this would prove difficult for my grandfather later on.

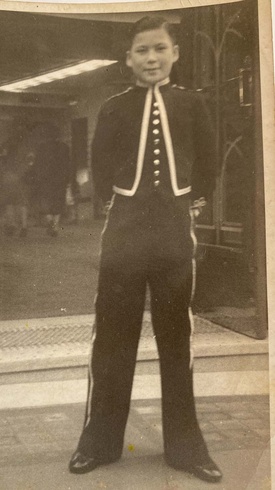

At age 12, when his family moved house, my pop decided to get a job instead of starting at a new school. Typical Tomo; he always did his own thing, never what was expected. Soon he was a “page boy” (usher) at the Hoyts Century Theatre on George Street in Sydney. This led to a lifelong passion and career in film.

Australia declared war with Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The next day, almost all Japanese in Australia were rounded up, including Pop’s father. Shojiro was 61 at the time and had lived in Australia for 39 years.

Shojiro’s eldest daughter, Aya, was interned in May 1942. Aya worked as a typist for a Japanese company. When interrogated by police, apparently she said, “I was born in Australia, unfortunately, but consider myself Japanese.” She was promptly interned, first in Liverpool (New South Wales) and later at Tatura internment camp in regional Victoria. She was 24.

Meanwhile, Shojiro was transferred to Hay internment camp in a remote part of New South Wales. His wife, Annie, continued to run both laundries in his absence.

On 15 May 1942, Shojiro was brought before the Aliens Tribunal. Shojiro spoke through a translator, even though he could speak English. When asked if he felt he had been wrongly interned, he said no. “I am quite prepared to stay here until the war ends,” he said, then agreed to have the application for appeal withdrawn. I read in Yuriko Nagata’s book Unwanted Aliens that over half the Japanese who appealed to be released withdrew their applications for fear of public reaction.

Shojiro learned via a letter from his wife that Aya was interned in Tatura. He wrote to the camp commandant, requesting to be transferred to join his daughter. His request was granted and he finally reunited with Aya, spending two months with her in Tatura camp until she was released just before Christmas in 1942. A national security report noted that Aya denied making the earlier statement about considering herself Japanese, and said the officer had been brusque with her and had angered her. The report concluded she posed no danger despite her “very Japanese appearance.”

Shojiro, however, had to remain behind barbed wire. He became very ill and was transferred to hospital a few times. He was released in June 1943, aged 63, owing to his poor health. Seven months later, he died from tuberculosis and myocarditis at home with his family in Sydney.

Just two weeks prior to his father’s death, my grandfather Tom (he used this name henceforth) enlisted in the Australian army, aged 18. He had tried to enlist in the air force, but had been rejected. His older brother Kazu had already been in the army for a year.

I asked Pop how he was treated by his comrades as someone of Japanese descent. He said he told them he was Maori and that was acceptable.

The Australian army, however, was very aware of my grandfather’s heritage. Security reports detailed his father and sister’s internment and concluded the family posed no risk. They also noted that he was “typically Japanese in appearance,” and thus shouldn’t be given “duty of a secret nature,” lest he fall into the hands of the enemy.

Pop was determined to be sent on active duty. Knowing he wasn’t allowed to go north because his father was Japanese, he wrote a letter to the minister for the army, pleading his case. “My mother is a British subject (Australian born) like the rest of the family, all of which are loyal to Australia,” he wrote. “I feel it is my duty to do my bit for King and Country so I hope you can rectify my problem.”

The letter must have worked, for Pop was sent on active duty to Papua New Guinea as part of the army’s cinema unit. He was given a projectionist set to entertain troops. At one point he severed his finger in a projection reel and required surgery. It didn’t stop his love for cinema, though!

During his time in the army, Pop also marched the Japanese to Hay camp after the Cowra POW breakout—the biggest and bloodiest prison escape of WW2: 1104 Japanese POWs attempted to escape and 231 were killed.

Pop said being in the army was the best thing he ever did. He had so much pride marching on ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) Day every year. As small children, my brothers and I crowded around the TV waiting to see Pop march down George Street behind the Cinema Unit flag. Each year, fewer and fewer of Pop’s friends marched with him, until one year it was only him. After that, he said he couldn’t walk the distance because he had emphysema. I told him to ride in the car behind the flag, but he said, “Never!”

My pop, Tom Omaye, died in 2018 at 93 years old. My grandmother, Mary, followed him shortly afterwards. Pop was ready to go after years of struggling with emphysema. This gave us all time to say proper goodbyes, but there are still so many questions I wish I had asked. Especially now that I understand the difficulties he must have faced in life.

Now I’m preparing to move to Japan soon. I’m so excited to learn about my ancestry, the culture and the Japanese language. I hope to find more information about Shojiro and his relatives, and in doing so bring the journey of my family full circle.

*A version of this story was originally published on www.nikkeiaustralia.com.

© 2021 Shey Dimon

Nima-kai Favorites

Each article submitted to this Nikkei Chronicles special series was eligible for selection as the community favorite. Thank you to everyone who voted!