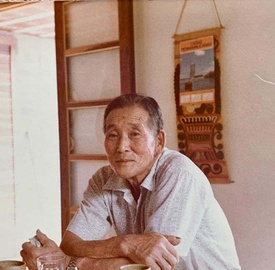

There was a time when we drank soft drinks out of glass bottles. Before the reckless use of disposable plastic, you went to the beverage supplier with a crate filled with empty containers and exchanged them for full bottles. My grandfather always bought the individual green bottles of guarana, leaving them in the fridge while waiting for the visit of his grandchildren. The hissing sound of the carbonation as the bottle opener removed the cap still takes me back to that kitchen, while still a girl next to that strong man who barely spoke the same language as me, but who made me understand that I was loved.

His was a bachelor's home. A messy form of organization; everything a little dark and a little old, the way things had been left by my obaachan, who had been dead for some years. It was a home frozen in time, in my grandmother's time. I never met her.

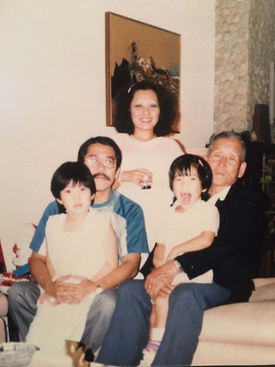

Both my father and my grandfather told me that she had died a few months after I was born, and that she died while talking about me. In the delirium that preceded her passing to the other side, she thought she was holding me in her lap while rocking me back and forth. And this scene, ingrained in my grandfather's saddest memory, was enough for him to come to believe that I was the reincarnation of his beloved wife. That's how I automatically became his favorite granddaughter.

I've no idea what his religion or creed was for him to believe such a thing, and for years I thought, “How could that be, since I was alive when she died, which means I already had my own soul? Could this be the reason for all my personality issues? Had my original soul been driven out or muzzled by my dead grandmother's?”

So my grandfather's love for me had been inherited from his love for my grandmother. It wasn't a love that I had earned for being myself. I was getting to learn little by little about love and I thought it was beautiful that Ojiichan continued to love his deceased wife after fifty years and with death itself keeping them apart. My father found it even more peculiar because he couldn't remember seeing any display of affection between the two: they were a Japanese couple.

I remember photos of her around the house and Ojiichan looking at them with tenderness, and then saying that he was tired and could hardly wait to die so he could be with her again. (Further confusion: so, did that mean I'd have to die for him to be reunited with her? Or was her soul going to abandon me, thus letting my original one flourish?) I couldn't understand his death wish; as far as I was concerned, no one wished for such a thing. I was shocked, so he explained it to me. My grandfather, my jiichan, asked me to sit by his side. He picked up the newspaper lying folded on the coffee table and opened the obituary page.

“I pick up the newspaper every day to see if friend died. To go to the funeral. Jiichan has more dead friend than alive. Dead wife too. Jiichan alone and tired.”

He was teaching me not to be afraid of death.

As a good Japanese man, at every festivity he would hand us a little money in an envelope. On the outside, he would write our names vertically, in kanji, and would then give it to us saying the money was for us to buy a notebook for school. My sister and I eagerly opened the envelopes and planned on buying all kinds of things, except notebooks.

For my grandfather, education was everything. He had come to Brazil while still young, without much formal education, and had gone to [the Amazonian state of] Pará to work on a black pepper farm. He made sacrifices so his sons could attend school, and they all did graduate: an architect, an economist, and an engineer. The daughter didn't go to school; she got married instead. But in the case of his granddaughters, he did want them to study. Times were changing, and so was he. In the notes that came with the money, the priorities of life were listed: 1) health, 2) education, 3) friendships. Your education, he used to say, is something no one can take away from you. He would go on teaching me.

At one time, he returned to Japan. It was the most momentous event of his life; he even got to meet the emperor's delegates. He was part of a group representing, on his side, Japanese immigrants in Brazil. He was given a gold tie clip with which he would eventually be cremated. That was his only important object; it featured an embossed sun spreading its rays, as in the flag of the now-defunct Japanese Armed Forces. Else, he had no attachments. He lived a simple life, like a good Buddhist. (I don't even know whether he actually was a Buddhist, as he seemed to mix a bit of everything, something typical of so many Brazilians.)

I used to give him socks as gifts because sometimes, when he took off his shoes at home, his socks had holes in them. After his death, when the family went to his place to sort out his belongings, I found all the socks I had given him still with their tags on and in their packages. Holding these new socks, whose owner was now dead, I learned to make use of everything that's given me instead of saving things for a special occasion, as such an occasion may never arrive, which would mean I wouldn't have been able to enjoy anything – not even good, warm socks. Besides, I also learned that he couldn't have cared less about the holes in his socks.

Affection has been mixed with guilt. My recollections of him are always filled with tenderness, but now, as an adult woman, I feel sorrow and guilt for not having enjoyed his company as I should have. When we're children, there is no guilt; that's something that quietly settles in as we grow up, during the night. One day we wake up and it's there, set in as if it had always been there, as if it were the oldest of all tenants. The worst guilt is the one associated with the very day he died. That one I've known for a long time, and it feels like it's going to live indefinitely inside me.

For a while, every time I went to visit him at the hospital he would ask me, holding my hand, to get him out of there, to take him home. Not knowing what to do, not believing that I had any say in this kind of decision, that this sort of thing was an issue for my uncles and my father, I'd pull out my hand and leave the room to cry. I felt as helpless as he did. I don't recall asking my father to get him out of the hospital; deep down, I thought he might have a better chance of surviving if he remained under medical care.

After his death, I promised myself that if something like that were to happen again, I would take the person home. I think we know when we're going to die; I think that's what he wanted to tell me. And he was already tired and wanted to go home. I learned from him about death and last wishes.

My Jiichan was the first dead person I saw. He had cotton in his nostrils, and his shoes had been cut off on the side so they could fit his swollen feet. He seemed to be asleep; I kissed him. My sister and I cried; we cried a lot, not knowing who was grieving the most. Witnessing my sister's sadness made me swear to myself I wouldn't tell her I had been his favorite. Today, after so much time, I don't think it makes any difference anymore. Except for myself, as my Jiichan was the first dead person who had loved me, who had made me feel special and important.

I cried for his death, but I cried more for myself. I cried because he was gone, because he had suffered; but I cried, above all, because I hadn't gotten him out of the hospital, and I cried because a person who had loved me was no longer in this world. That meant less love for me. I realized that I was being selfish in death, so I stopped crying. He had long wanted to be reunited with my grandmother. My grandmother who was then leaving me so I could become myself.

This year marks twenty-four years that he's been gone. He, who was born on Flag Day [Nov. 19] and was a Scorpio. I learned so many things from him. I don't know for a fact whether or not everything he was and everything he taught me was a consequence of his being Japanese, but the love he had for me, his presence, and all he did made me proud to have come from the same place as he, from the Land of the Rising Sun. I was proud, even though, while growing up in Brazil in the 1980s, I never saw myself represented in the media; or when I did, it was always in a derogatory manner, loaded with prejudice and stereotypes. I felt angry and I thought that what they were doing was bad, for nothing I saw reflected who either I or my ojiichan was.

Today, my father is the one who has become Ojii, and my Ojiichan lives in him. My children's Ojii calls them by their nicknames, gives them money in a paper envelope (but it's for them to buy ice cream and toys), buys manju, comes to sleep at our place, does some playful wrestling, teaches them to speak Japanese words, and tries to create affective memories like the ones I have of my Ojiichan. And like my Ojii, he goes on teaching the fourth generation about Japanese things and values.

Besides, he also has his favorite grandson, for deep down he believes that the boy is actually the reincarnation of his father. Everything remains the same. And life continues to go round in circles while Japan remains inside us all.

* * * * *

Our Editorial Committee selected this article as one of his favorite Nikkei Generations: Connecting Families & Communities stories in Portuguese. Here is their comment.

Comment by Claudio H. Kurita

It’s been a great pleasure and honor to take part in this jury. This year’s theme, Nikkei Generations: Connecting Families & Communities, has attracted a number of beautiful stories in which the authors convey their personal experiences with great intensity. The text that I’m highlighting was written by author Ana Shitara; titled “Ojichans,” it features various elements that are both touching and moving.

Her text allows readers to transport themselves to its many settings and thus recall their own ojichans (grandfathers) and obachans (grandmothers), and the time during which they lived in our country. Throughout the text, the author emphasizes an array of feelings—love, affection, guilt, and regret, among others—that bring it all closer to home, as these emotions are common in all families: a great clash of sensations.

At one point, she mentions how education was important to her grandfather. This offers a portrait of the beliefs of a large segment of the first and second generations: Hard work would provide the necessary means and support for their children to improve, through their studies, their living conditions and thus enjoy a better future.

Today we can see that the sacrifice was worth it, as many descendants belonging to the new generations have indeed managed to improve their social and financial conditions, while we also see many Nikkei playing key roles in various professional fields.

I must be grateful to my Ojichans and Obachans who did the same, and I congratulate Ana Shitara, who for a few minutes allowed me to fondly remember my grandfathers—Maruo-san and Akikazu-san—while thanking them in prayer for their dedication.

Thank you, Discover Nikkei, for the invitation, and keep up this wonderful and important work that helps with the integration and dissemination of Nikkei culture.

© 2021 Ana Shitara