As part of my research for Discover Nikkei, especially during COVID times, I spend a great deal of time perusing databases and digitized collections available online, such as Densho, the Library of Congress, or the Bancroft Library at University of California at Berkeley. As social distancing restrictions shift, occasionally I have the opportunity to visit university archives to see the actual documents. While online archives provide scans that are readily downloadable as computer files, the feeling of seeing boxes of paper and holding historical documents instills a distinct feeling of wonder that has become rare during the pandemic.

Recently, I had the chance to visit the University of California at Davis Special Collections to examine the papers of William Koda – one of the proprietors of California’s oldest rice farm, Koda Farms. Founded by William’s father Keisaburo Koda in Dos Palos, California in 1928, Koda Farms is still known as one of California’s main producers of rice.

When I initially requested the documents of the Koda family, I didn’t know quite what to expect. On their website, the UC Davis Special Collections had listed a brief description of the boxes as containing letters and photographs belonging to William Koda. I ordered up the documents and anxiously awaited to see what the archivist would bring out of storage. One box came with hundreds of Kodachrome slides and film negatives from the 1950s. I then found another box. This one contained tin cases housing countless reels of film, which sadly I could not view without a projector.

Finally, I came across a real find: a photo album kept by William Koda during his college years. As a student at UC Davis (then known as the College of Agriculture) from 1934 to 1938, William Koda had kept an album depicting him and his friends operating tractors, travelling to the Rose Bowl and Yosemite, and attending various student dinners on campus. Some of the photos showed daily operations on Koda farms, such as the construction of a rice dehydrator, filling rice sacks with a grain chute, and repairing tractors. A photo of William Koda’s cat perched atop a table stole the show for me. Seeing these photos of intimate life and everyday activities on the farm seemed like opening a window into the distant world of prewar life at Koda farms.

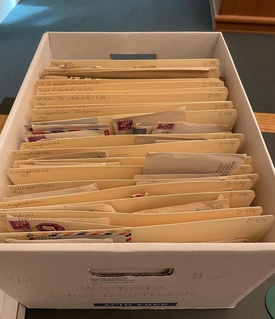

After reviewing the box with the photos, I requested the next box, which was labelled “correspondence.” This box was stuffed with correspondence, telegrams, notebooks, and newspapers. I was eager to see if they provided more details about farm operations. Instead, I was surprised to see that every file in the box was filled with documents relating to William Koda’s death and its aftermath.

William Koda died on September 6, 1961, succumbing to kidney failure at 43 years old. His sudden death sent shock waves throughout the West Coast Japanese American community and the city of Dos Palos. William Koda had distinguished himself as a country trustee for Merced county, and was so active in city politics that he was often called the ‘acting mayor’ of Dos Palos by city residents.

Leafing through a dozen folders in the box, I felt a sense of William’s importance to people. Letters in Japanese and English addressed to both William’s parents and his wife Jean poured in from organizations such as the Kashu Mainichi, the Nichi Bei Times, and the Tokyo Bank of California. Famed photographer Joe Rosenthal – known for capturing the raising of the U.S. flag over Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima – sent his condolences to the Koda family on behalf of the Press and Union League Club. A notebook accompanying the letters listed the names of hundreds of families and community leaders from across California who had written to the family.

One letter that stood out to me, however, was from Leslie Gillen, an attorney representing the Koda family. The letter included a message sent by U.S. Court of Claims Commissioner C. Murray Bernhardt. Along with his condolences to the Koda family, Bernhardt shared his concerns about the death potentially affecting the status of the family’s claim. The reason for this was that at the time of William Koda’s death, the Koda family was in the middle of filing a claim for financial losses incurred as a result of their incarceration at Amache Concentration Camp.

Following the passage of the Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, the government allowed Japanese American families to file claims with the Justice Department, as a form of restitution for property losses caused by their wartime incarceration. The Koda family’s claim, for the loss of their rice and hog farms and equipment, was the largest claim ever filed under the act, amounting to $1 million in property losses and $1.4 million in lost profits. Almost four years after William Koda’s death, in October 1965, the U.S. government at long last awarded the Koda family a claim of $362,500 dollars. As the Los Angeles Times reported, the Koda family received the last government claim for damages from the incarceration. The story of their claim will be the subject of a future article.

Looking at the box of letters, I sensed both the magnitude of William Koda’s influence and his adoration by the community. Although photographs and letters only tell one part of an individual’s life story, they leave behind a representation of one’s life and how they, or others, want (them) to be remembered. While William Koda’s legacy naturally lives on through his family and with Koda Farms, opening those boxes in the archive also opened a door for me into his eventful life.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen