Uruguay (official name: Oriental Republic of Uruguay) is a small country in South America with an area of just 170,000 square kilometers (about half the size of Japan) and a population of 3.5 million, roughly the same as the city of Yokohama. The country recently became a hot topic in Japan when former President Jose Mujica visited in 2016. At the time, former President Mujica gave a lecture at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies1 and was introduced on television as "the poorest president in the world2 " for his frugal and friendly nature. Recently, the country has also attracted attention for the fact that lean "Uruguayan beef" is being provided to yakiniku chain restaurants and meat specialty stores3.

However, what is not widely known is that there is also a small Japanese community in this country, numbering around 350 people. Moreover, Japanese people first immigrated to Uruguay in 1908, the same year as Brazil, so the country already has a history of 113 years. Furthermore, in December 2018, marking the 110th anniversary of Japanese immigration, Prime Minister Abe became the first Japanese Prime Minister to officially visit Uruguay, and had the opportunity to meet with local Japanese people4 .

Although it may be a coincidence that the history of Japanese immigration to Brazil and Uruguay began in the same year, there is a connection behind the two. At the beginning of the 20th century, Uruguay and Argentina were very cautious about accepting Asian immigrants, and it was prohibited by law5 . In June 1908, the Kasato Maru arrived at the port of Santos in neighboring Brazil, carrying about 800 Japanese immigrants (a group migration), and Japanese immigration to Brazil began. A few months later, some of the Kasato Maru immigrants from Okinawa Prefecture relocated to Argentina, and the migration of Okinawans to Buenos Aires also began that year. Meanwhile, Argentina was a developed country at the time and had one of the world's leading purchasing powers, so it was a huge opportunity that Japanese trading company employees looking to expand their business could not miss.

On board the Kasato Maru was Takinami Bunpei, who already ran an import goods store in São Paulo and Buenos Aires. 6 Takinami first visited South America in 1905, accompanied by Tsubota Shizuhito, who would later be dispatched to Uruguay. Takinami had opened stores in São Paulo and Buenos Aires selling Japanese pottery, silk fabrics, paintings, and Oriental art, and it was for his own trading business that he boarded the Kasato Maru in 1908. In order to expand his business to the Uruguay capital of Montevideo, Takinami dispatched Tsubota, who was already working at Takinami Bunpei Shoten in Buenos Aires at the time, to serve as the branch manager of Montevideo, Uruguay. Although this would be called a "corporate transfer" today, Tsubota stayed in Uruguay and married a Uruguayan woman, starting a family, making him the first immigrant to Uruguay.

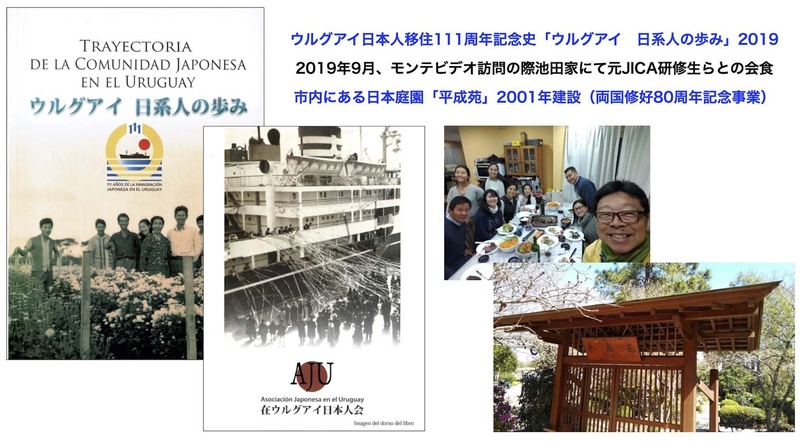

I first visited Uruguay in 2009 to attend the 15th Pan-American Convention of Japanese descendants (COPANI). 7 Since then, I have developed close ties with Japanese descendants in Uruguay through JICA trainees I met in Japan. Last year, a friend in Montevideo sent me a commemorative history published in 2019 entitled "Trayectoria de la Comunidad Japonesa en el Uruguay - 111 Años de la Inmigración Japonesa en el Uruguay" (hereafter "Trayectoria of Japanese descendants"). The book features interviews with 53 Japanese and Japanese descendants, as well as some notable anecdotes, and offers a glimpse into the lives of Japanese descendants in the prewar and postwar periods.

Looking at the testimonies of these 53 people, we can see that a considerable number of them have relocated to Uruguay from Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, etc., both before and after the war. In recent years, there have been many cases of people settling in Uruguay due to international marriages, soccer, or business. It seems that many of the pre- and post-war immigrants made a living by cultivating flowers, and I found it very interesting that some of the books described the connection between flower cultivation by Japanese immigrants in Uruguay and Argentina.

Many of the immigrants involved in petal cultivation started out as tenant farmers, or "medianeros," for Italians and others, and gradually moved to Paso de la Arena, 16 kilometers west of the capital, Montevideo, to cultivate flowers. The average farm size was about 5 hectares, and like Buenos Aires, they seemed to have focused on selling cut flowers before the war.

After the war, before flowers began to be imported from Colombia around 1980, there were large-scale floriculture businesses, including Mizuki Tadao. Mizuki had 100 greenhouses and produced small chrysanthemums on 16 hectares.8 The most famous was Takadaen, run by Takada Naoki, which also had a Japanese language school and hosted Japanese events such as sports days.

Thanks to the many successful pioneers from before the war, some people from Japan immigrated to South America to train as agricultural trainees at Japanese floriculture farms. After learning the cultivation methods, many of them became independent and started their own farms, while others brought new varieties of carnations, gladiolus, etc. from Brazil and Argentina. Of course, some returned to Japan, but many remained in South America.

The Japanese Association was established in May 1933, with Nakamura Shosuke as its first president. At the time, there were only ten Japanese members, but by the following year this had increased to 22. In 1941, Tsubota Shizuhito, the first immigrant to Japan, was appointed president of the Japanese Association, and in November of that year, the first athletic meet was held at the Misagawa Garden in Paso de la Arena.9 During the war, bilateral relations between Japan and Uruguay were suspended, but it seems that some Japanese people went to Paraguay or Brazil, got married, and then returned to Uruguay. In "The Journey of Japanese People" (published in April 2019), there was a testimony of one Japanese who "miraculously managed to return to Uruguay."

Immediately after the war, many people were cautious about reopening the Japanese Association, and initially, only a few influential Japanese people gathered to hold events and ceremonies, and only sent bouquets and donations. In 1952, an international film festival was held in Punta del Este, known as a resort town, and the Japanese film "Rashomon" was screened. At this time, many actors from Japan visited Uruguay, so members of the Japanese Association and their families held a welcoming party, which led to the reopening of the Japanese Association after the war. From this time on, agricultural trainees and new Japanese people began to come to Uruguay, and the activities of the Japanese Association gradually increased. Yamamoto Hisao, who had been successful in floriculture before the war, and others played a central role in the development of the Japanese Association.

Notes:

1. Video of the performance at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies: Lecture by former Uruguayan President Mujica (with simultaneous interpretation) (April 7, 2016)

2. When he was young, Jose Mujica and his wife were guerrillas in the far-left extremist group "Tupamaros". Mujica was injured and arrested in repeated armed clashes with the military, and was imprisoned for more than 13 years. He was later pardoned and released. He has been active in politics since 1985, and in 2009 he was elected president by a left-wing coalition. Although he is said to be the "poorest president in the world," he is not actually poor. Mujica's wife, Lucia, is also a politician and served as Senate President and Vice President. As a result, he was able to live comfortably on her salary alone, so from 2010 when he became president, Mujica donated most of his salary to the foundation of his political party and requested that it be used for social welfare projects. He also did not live in the official residence, drove an old car, and lived a simple life in a house on the outskirts of Montevideo, which is why he was called this. In 2020, both of them retired from politics and are living a peaceful retirement life.

3. First introduction at a chain store in May 2019: " A thorough introduction to the appeal of the 'super thick, aged' sirloin from Uruguay, the beef powerhouse! (Bronco Billy, May 20, 2019)

Introduction to Natural Beef (Brain Livestock Industry Organization) " Characteristics of beef from Uruguay, described as 'Natural Beef', and the outlook for exports to Japan "

4. Meeting between Prime Minister Abe and Japanese people of Japanese descent and Japanese residents in Uruguay (Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Summit meeting with President Tabare Vásquez (Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Japanese Nationals and Japanese Descendants in Uruguay (Embassy of Japan in Uruguay)

5. Argentina was also quite cautious about immigration of Asians, and after Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, conservative politicians were seen to be wary of the presence of Japanese people. However, interest in and admiration for Japan was also growing, and it was a time when some intellectuals and merchants tried to establish relations with Japan, and conversely, the number of trading company employees coming alone from Japan was also increasing.

6. Fumpei Takinami never settled in Buenos Aires, but he visited the city a total of eight times. His eldest son, Fumio, stayed in Argentina, and his descendants still live in Buenos Aires today. In 1904, there were 15 Japanese people living in Buenos Aires, and ten years later, the number had increased to 1,007. After that, the number of Japanese people relocating from neighboring countries continued to increase, and many of them ran not only small trading companies but also cafes in urban areas.

7. Alberto Matsumoto, " Pay Attention to Developments in Montevideo COPANI and Uruguay " (Discover Nikkei, May 20, 2010)

8. “The Journey of Japanese-Brazilians: 111 Years of Migration History Trayectoria de la Comunidad Japonesa del Uruguay, April 2019” (Testimony of Mizuki (Tanaka) Yoshiko, page 58)

9. The Japanese Association in Uruguay (edited by Yamamoto Hisao, Ohno Kiyoshi, Umeki Kazuo, etc.), "History of the Development of the Japanese Association in Uruguay," published in 1973 (Showa 48)

© 2021 Alberto Matsumoto