How long were you in Santa Anita?

I guess it was about eight months. And the thing is that to bring some solace to the crowd of people, they had a group of Hawaiian singers and dancers, and there would be a stage where they would have some sort of intimate entertainment. They tried to start some classes to try to maintain the education. But I don’t think that was successful at all. And then Santa Anita, they did have a program underway, they started to produce camouflage netting. So they had on the stands, people were working on camouflage netting and they got about six or eight dollars a day or something like that. And some people didn’t have enough money so they did work like that. Every dollar counted.

With the exception of entertainment things, there was nothing organized so I wandered around. And when I try to recall what I was doing there, the things I remember most in my mind these days is sitting next to a shower, on a bench. I would sit there on the bench and look outside and I can see the Arcadia traffic. And I [said] I don’t know what my future is. I see these cars moving freely here in camp. There’s nothing to do, I’m bored to death. If you have to go to school, you have to wake up there was a certain routine, the regimentation there which I was subjected to when I’m 16 years old, but they didn’t have any kind of supervision. So if you’re a child you could do anything you wanted. So there is that kind of lack of recognized authority. They had guards posted, but within the camp itself, it was chaos in a way. Boredom. That’s like being in jail. There’s no stimulus at all, no change.

Yes, the days just bleed one into the next. And so what was the train ride like going out to Jerome?

Well, we didn’t know where we were going. And I don’t recall how I slept, but I don’t think they had beds but they had probably reclining chairs or something. But I remember it was a long trip. It took from what I gather three nights. And most of the time you recognize it wasn’t running during the daylight hours. You would go and they would park along the side and you wait and there’d be trains coming back and forth. At night when it did run you had to close the blinds, no light escape from the car. So you were isolated in that way. And see at that time there were rumors that Japan might invade the United States. That was purposefully presented by the government or something to keep people in check. But that wasn’t really the case at least in California. But I remember on that train ride, there was an African American steward or a person that looked after us in a way. And we’d be passing some mountainous area and he stood there and I overhead him say, “Man, don’t you think this is pretty? This is God’s country.” There’s just a contrast of one person doing something and thinking, it’s beautiful, serene. But in my case, I didn’t know where it would end.

And there were mothers with children that I’m sure it’s been difficult because mother’s milk and all this kind of thing is impacting the child. I heard at a meeting that I went to after the war in San Francisco where people were expressing what the experience. And there were mothers at that meeting that stood up and told about losing their child. I don’t know if it specifically related to a train ride, but listening to that you say, you’re thinking about yourself, but how about mothers with young children like that? That they’re trying to do what they can to alleviate hunger. That’s one of the reasons why we had demonstration because they lacked sufficient milk. In some cases and in many cases, meat. There was absence of meat, presumably because maybe a little black market in which people that were assigned that were selling that off the black market. It’s all these little things that crop up, and these are the memories.

Did you ever speak with your mother or your sisters at any point?

No. See this is what I mean. I may have or they might but I don’t remember a word, their attitude. I don’t know.

And then arriving in Jerome. What was that like? You know and going to Arkansas from L.A. What were some of your first impressions from arriving there and seeing that landscape?

Well, it’s strange ’cause it’s a strange environment. I think the thing that was striking was the fact that they were uniform lined huts or barracks. This was patterned after the military barracks for soldiers. You had units of six rooms or positions within each barrack for different families or individuals. And some of the areas were concentrated by people from a particular district in California, Hawaii. So there was a block at the corner, they were largely Hawaiians or Japanese Americans from Hawaii. Los Angeles was sent very close by, not out of state. The reason why is we went [is] Renko’s family was headed by a doctor and he was distributed to these areas where they needed doctors so the doctor would decide a certain center. So we as a group lost all contact with the neighborhood Japanese Americans. We were talking with other Tulare or Fresno or something like that. But very few from Boyle Heights.

And did you start school again?

Well after a while it wasn’t immediate but there was an absolute need for school. So I don’t recall when we started, but they started to open up the schools and they had to get the teachers. And the thing that struck me was that there were classes headed by teachers that were teachers, like in chemistry, that knew very little chemistry because I went to Theodore Roosevelt High School and it was very good because you had teachers that had some experience with Caltech or something like that, they were very advanced. So the students were pretty well advanced in math and science areas.

So you graduated in 1943. So kind of in the middle of the war. Do you remember when the loyalty questionnaire came out?

Oh yeah. Basically, I didn’t know how to answer that question. And I was debating that question. My older sister was living in camp with the doctor as her husband and I asked her what I should do ‘cause I didn’t know, looking at what is happening to us. I had some serious doubts about whether I should sign that. So I went to my sister and the immediate response: “What do you what do you think I should tell you?” And she told me, ”You better sign that ‘yes.’” She was quick, said, “You were born in this country, you were raised here. You’ve never been to Japan. How can you disavow that?” And to this day, that simple response had a great impact on me because when I came to Ames here, working for NASA, I head up a group of researchers. I was for a while involved in recruiting new people to Ames in the life science area. And as a consequence, I had to undergo a security clearance. And I passed the security exam — they go through a intensive investigation. And I realized that my assessment as an individual was very positive. And I got a secret clearance.

Well, I happened to meet someone [a Japanese American] in San Jose who was also a scientist. He was applying to Lockheed Corporation which was next to Ames. And he said that he had applied but got turned down. He says, “It must’ve been that I didn’t pass a security test.” And I have a feeling that’s the case that people that signed no/no at least for a while was considered disloyal, or what. At that time, anyone who said “no” went to Tule Lake.

So they went back that far? They looked back through the records?

Oh yeah.

Can I ask what year this was that you went through that security clearance?

That must’ve been 1962, ‘63, something like that.

So they still considered that answer within your ability to be working.

Oh yeah. Well, what I’m saying is that they erred on the side of extreme security. Whether you have had a change of heart or whatever, it’s on your record and you have to wait until the thing changes or is somehow expunged from your record.

So your sister’s response in being insistent to say yes/yes, really impacted your life.

Oh yeah, it did. Because if I said no, I wouldn’t have had this job at NASA. And so I’m indebted to her. She was a surrogate mother in many ways, my older sister. Because our mother was Japanese the camp existence turned that relationship of protection and advice upside down.

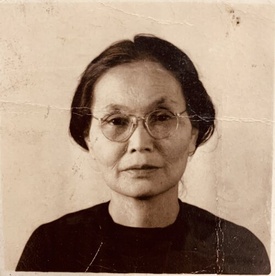

The other thing I want to bring up, it’s really a post-war thing. I should bring this up that my whole life, the evacuation was a very, very primary cause. But my experience after my discharge from the army, it happened that my mother exhibited a dementia paranoia. When I was discharged in Illinois, I went to my youngest sister who had an apartment there. And I stayed there for a couple of days. But my mother at that time was undergoing an attack of dementia paranoia. And it turns out that my mother after leaving camp and working in Cincinnati and later on in Chicago, where I became more conscious of what she was doing — she was working in a clothing factory. I was talking with someone who was her supervisor, commending her for working so hard. They said she never she never took a break during the noontime, she would work continuously. And that was abnormal.

But one of the reasons why was that she had just paranoia of having done something wrong, which is really translating to the fact that her mother country attacked this country. So in a sense she was trying to compensate for that, being ultra ultra strict. And the other incident that involved this paranoia was that she had encountered trouble on a bus. And the bus driver called her back and said, “You didn’t put enough money in that thing.” She probably did, but he accused her of that. And as a consequence, she put money. But every time, she goes out to travel by bus, she had put in more money than was necessary to make sure that that didn’t happen again. So that extra sensitivity, is probably paranoia. When we lived together in Maryland — this is again after the war — I had bought a G.I. house in Maryland. I used to take her occasionally to Washington, D.C. And I had a car at that time. And I would tell mom, we’re going to Washington, D.C. And she’d go out to the car and look at me and says, “We’re not going to the police station are we?” She’d always do that. Because the last time she did that, she had an attack. And it was a pretty terrible, schizophrenia-like, delusions and everything else. And living with her, I had to go back to Chicago. And anyway, she was institutionalized.

I drove her to Chicago from Maryland when she had this attack - it was impossible to handle by myself. I was working and going to school and taking care of my mother. But she was able to live by herself when I was gone but when she had these attacks, it was impossible. She had to be restrained. And so, I took her to the local health place and they said she’s not a resident of Maryland and you have to be at least here for three years before. And so I had to take her back. So I drove. Looking back, I couldn’t do this now — from Rockville, Maryland back to Chicago nonstop at night, I didn’t know the roads. I had to get onto a highway that criss-crossed Pennsylvania. I didn’t know where I was and I was following a car. My mother occasionally had an outburst.

What was she experiencing? It was schizophrenia?

It’s dementia. Mental breakdown. She broke down and her excuse you might say was that she was not guilty. It was not — she was taking it at a personal level — that she thinks because she was Japanese, Japanese, American, had lost her family structure, had to live life with her only son, who’s not married, working. It must have been that she felt responsible or something like that. She wanted to show that she was innocent of any crime to be punished. So I remember, she’d look at me and say, “You’re not going to take me to a police station?” I said, no, I won’t. All of this thing stems from persecution, the sense of guilt, paranoia, thinking that everything is against you.

But when I drove this nonstop to Chicago, my older sister was there with her husband and we had her institutionalized and she did go through Chicago Medical, one of the psychological hospitals. And after about one year, I visited her when I had a break after a year, and the first thing that I remember is embracing her, she comes running down to me. She was not in a nightgown, but it was certainly not a dress. And she put her arms around me and hugged me. And I felt there was something in her dress. And as it turned out, it was all these letters that I had been writing. I had been writing two or three times a week. And she kept them. They all were in her breast area, she kept them.

So I after that, I said I can’t allow this to continue. So I was about to leave and a lady who’s a Nisei, was a receptionist or something and she knew about my mother and she comes up to me and says, “Hey, this is apart from my position but what I would do is leave your mother here because she’s not going to get well, there’s no treatment. No one understands her. It’s your life, at least.” That’s what she told me, she says this is my own personal response. I looked at that; I had already a feeling that she was undergoing something terrible. I took that to heart, talked to my sister and her husband, and we had a series of shock therapy, shock treatments done.

So after that, we flew back. Somehow, I don’t know why I think we flew back because she later on in her sane moments she told me it was her first time she was riding an airplane. She noticed that things are turning around. I got her back and she came back and lived with me for the rest of her life. I was responsible for her. And it was a wise choice because if she hadn’t been left, she wouldn’t have died but it was secondary, it was something that was curable that I could have taken her out, given her treatment because electroshock therapy was the main so-called curative treatment. It was not really totally effective, but it was combined with tranquilizers that came into being in early 60s. All the rest of her life, I’ve been responsible for her, taking care of her until she passed away.

How old was she when she passed away?

She was 87, something like that. She died in 1971. She was born in 1884.

This is so heartbreaking. Because I’ve heard this similar story, and only women seemed to go through this kind of mental breakdown, nervous breakdown. And then again, the medicine at the time or psychological resources weren’t available. No one knew what to do. Could you ever talk to her as she was older, like when you were taking care of her?

Yeah, I think she had her sane moments. And as far as traumatic episodes, there was none as compared to what happened in Maryland. She didn’t have much contact with neighbors or strangers or anything like that but she lived for five years by herself.

To be continued ...

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on March 1, 2020.

© 2020 Emiko Tsuchida