This is actually good because it brings us to Pearl Harbor. So your father’s gone and it sounds like your sister's becoming the head of the household. So what do you remember about the day Pearl Harbor happened?

It happened two years after my older sister got married. So we had my younger sister, my brother, and me. My second sister, Minnie, was managing the grocery store. And my brother is starting to go at that time to UCLA. And I was about 16 years old.

So on Pearl Harbor, we used to close the store on Sunday afternoons. And I remember receiving notice that on the radio there was an attack on Pearl Harbor, and nothing in detail but they’re talking about the Japanese: “The ‘Japs’ attacked Pearl Harbor.” And the next day was Monday and I was concerned about what happened. During that time, all Japanese Americans must have been worried, too because it was their mother, father’s country that did this attack. So I went to school and all I remember now is that we stood on the football field. All of us. And we were listening to the President of the United States. The thing that struck me to this day I don’t forget is that “day of infamy.” I had never heard the word “infamy.” But that would describe the Japanese attack. A day of infamy.

And as I was standing there, I was looking around to see, realizing that everyone was concerned about the attack, that they would be looking at me. I didn’t consider other Japanese, too. It was me that was to blame. That was that inherent assuming of the responsibility for your mother’s country. That I remember about putting my head down and trying to fend off presumably people that [would] say bad things about me.

That was what I remember. But going back to the store later on, from that time on, of course, our lives were completely changed. The customers that used to come to the store, some of them just quit completely. So we lost customers and there were new customers that were coming. I mean, a few. And it turned out to be that they were probably trying to compensate for those people. Certain people take sympathies or they show it in some odd way, but they may come to a store that they would never go to with a nearby Safeway available, but they would go out of their way to show that they had some sort of empathy. And I’ll never forget that duality of people in a mass like that. The response is not all negative or all positive.

I have a flyer, the Executive Order 9066. I was reading that before I came over here. And I was looking at the instruction of what we could do or not do. And where we should report. My god, I didn’t read that 9066 when it came out, but in retrospect, preparing for this I thought, what was the thoughts that were evoked by the Pearl Harbor and how did it affect the family? And of course, that set of directions were very very forthright. Japanese ancestry. It’s not whether you’re a citizen or not, it’s Japanese, you are told not to assemble or certain streets you could not use. You have to meet at a certain place. If I read that and I said oh my god. That would be hard to comply with anything. But to have people like me born and raised this country, innocent of anything but being subject to that. Well our response was, we knew that somewhere along we’re going to have to report and we’re going to be able to only take certain things.

So we started immediately to try to get rid of things. And you couldn’t sell it ‘cause it was evident that news got around that you could buy cheap things [from these] “Jap houses.” So it was a very hectic time between that and the actual evacuation. But just to think, they tell you, you should only carry enough clothing and things that you can carry in two suitcases. And I was a young kid like that. My mother and the family were all considering or thinking about where to buy — you’re concerned about these little niceties, about what you should carry. You didn’t know where you were going. You really didn’t know what the future would hold for you. And that’s a thing that’s utterly strange for someone like me who’s raised to think you’re American. I would never want to go through that, I would never want anyone to go through that exposure, where the government itself is telling you what to do, divest yourself of any rights you have. It’s inconceivable. And to this present day when you have people being treated that way from another country just because of a border. The philosophy, the belief of that president that we have, is something awful.

It’s not learning from an experience that we all know is wrong. And that’s what’s really scary. I’m wondering about your mom because she lived on Oahu. Do you remember how she responded after the attack and did she say anything to you?

I don’t remember anything she said to me. I think in my way, I think maybe your ears are not open to anything. You’re so scared of everything that you don’t consider how other people are taking it; it’s yourself. And the thing that’s etched in my mind was there were a few Korean people that had restaurants or other things like cleaning shops or something in Boyle Heights. But I know walking along the street sometimes you would come across some Asian person. And it’s either Chinese or Korean [that had] a badge: American flag and a flag of maybe another country. But anyway, they had an American flag. Said, “I am an American.” And phew, I used to see that and say, “Why can’t I wear that?” That would be deception to say I’m an American and expect equal treatment. That’s the thing. You have to feel that sometimes they are as equally insensitive to the plight of other minorities, even though they are experiencing the same phenomenon. You have to go through this. I hope most people who do go [through] it develop a sensitive awareness for other people.

But the Japanese Americans are relatively pretty loyal. And that brings up this point of, getting off the subject. I have consistently been for most of the people that are the no/no boys. Most people it’s very common, ordinary to applaud the 442nd, ‘cause people have lost their lives. So I had a great admiration and sympathy towards 442nd, but the same time, I respect those people that stood up against the evacuation.

That’s interesting because then you went on to serve. But maybe we can start first with some of the details about starting to leave L.A. Did you go to an assembly center first?

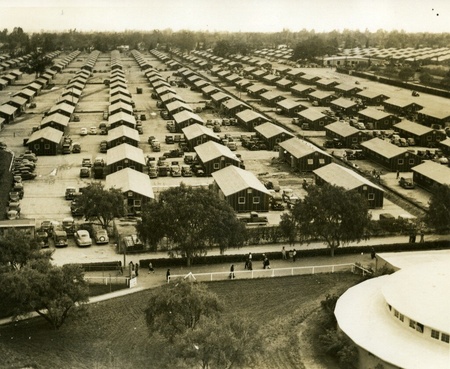

Yeah, I went to Santa Anita.

And what was that like?

Well, our family moved temporarily for one day to West Los Angeles, it’s where my elder sister was married. And she wanted basically the family to stay together during this time. So she involved paperwork so that when we moved this one day to that area, we became residents of that area so that we would be evacuated to the same center. We didn’t know where we were going, but we liked to be together. So we moved to this church in West Los Angeles. And at that place there was a lot of buses and things like that, there are cops. People went into the bus as a unit and we moved — you’re not conscious of all these small details at that time. You just worry about your baggage and whether you stick together.

And we got there, my first impression was, oh, it was like a track but it was congestion. You saw so many Japanese Americans. That was part of the thing. But then when you registered and your family was assigned a billet, it happened that we were assigned a billet that was former horse stables.

So they send us to a block where horse stables were converted to living quarters and our family of four — mother, two boys and a girl — were housed in this one room, large room, with four beds, and we were told to go out and get mattresses. So we went in there and then the shocking thing of course, is lavatory facilities and dining. The dining room was maybe a couple of blocks away. But the toilet was nearby but it was half a block away or something. And when you went into that thing, the men’s room, all the urinals were open. Shower, there’s no separation. So there’s was no privacy whatsoever. And I presumed that the females were the same and they were affected more.

So the people that had to do this stuff had to do it, sometimes tolerating that or doing everything after hours when everyone else is sleeping. So this lack of individual privacy was destroyed, and that was the thing that struck me as being so important because as a family you had your own privacy and your own house and there it was open, there’s no barriers at all. They stripped you of all your individuality, your privacy.

And dining was another thing. One incident is, I was wandering around the center and here’s another thing, there’s no organized thing for people like me, a student in midst of school. There was no school. And so you had your spare time sitting around. If you had friends you would talk with them but if you were more of a solitary, and I was more or less a single-minded person, I had no one like a youngster of my age that I could consort with. But I remember being curious about a mob of people around the entrance way to a dining room hall. And I approached them and all of a sudden the people started to turn around and started to move toward me against the direction of the dining hall. Not exactly a mass rush, but people were walking very rapidly. And at the same time, I saw a Jeep come in, it was a military group with the man on the back with the mounted police, a machine gun. They were using that Jeep and machine gun to herd the people or to tell them that they should disperse or something like that. I was 16. I turned around I thought they were gonna kill us. I really felt that all for one reason or another, they could pull a trigger.

So I ran, and I ran towards my stable and got home. I got back to the stable and I happened to listen to the radio, the local Arcadia station. That noon, the announcer came on, said that there was a riot or something, a demonstration. And that the reason why they were demonstrating was that their menu included sauerkraut and wieners. Well, it’s the association of sauerkraut and wieners was Germany. And if you’re German, you obviously like sauerkraut and wieners and the Japanese Americans are still loyal and therefore they are demonstrating against Germany [laughs]. They wanted to absolve the Japanese act as being, you know, not good, but the Germans are or worse. So if the Japanese Americans in camp control the loyalty they control it by that way. That was a real joke, was a farce. The demonstration was instituted by mothers of young children that weren’t getting the proper nutrition.

And so they were demonstrating. But I’ll never forget that because at 16 years of age you read the newspaper, listen to the radio, you thought that was legitimate that’s part of government. And at that moment I think I became a mature individual. And ever since then, you might say, I’m very critical about things that are done or not, because any kind of event that’s announced has two sides. You got to hear both sides. That is important to me. A product of this evacuation is it started me on the way towards being critical of anything.

And the thing is that in Santa Anita, they gave us no information. Towards the end we were evacuated from Santa Anita to Jerome, we didn’t know where we were going but at that moment towards the end, there was an announcement that people in certain blocks will have to move and they would come on board and say goodbye. But that was it. You didn’t know. You didn’t know where you’re going — would you ever come back? What would be your status here? You may be gone forever. There was just uncertainty.

To be continued ...

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on March 1, 2020.

© 2020 Emiko Tsuchida