Chicago’s Near North Side. In the early to mid-twentieth century it was a playground for the rich, transient stopover for the poor, home to beatniks, hippies, harlots, the Rush Street entertainment district and the Outfit. Historically a multi-ethnic stew, within its boundaries could be found Swede Town; German Broadway; Little Sicily; an Irish settlement on Goose Island called Kilgubbin; and La Clark, a Puerto Rican enclave displaced in the 1960s by Carl Sandburg Village.

In 1929, Harvey Warren Zorbaugh wrote about Chicago’s Near North Side:

Clark Street is the Rialto of the slum. Deteriorated store buildings, cheap dance halls and movies, cabarets and doubtful hotels, missions, “flops,” pawnshops and second-hand stores, innumerable restaurants, soft-drink parlors and “fellowship” saloons, where men sit about and talk, and which are hangouts for criminal gangs that live back in the slum, fence at the pawnshops, and consort with the transient prostitutes so characteristic of the North Side - such is “the Street.” It is an all-night street, a street upon which one meets all the varied types that go to make up the slum. (Harvey Warrren Zorbaugh, The Gold Coast and the Slum. The University of Chicago Press. 1929.)

Prior to WWII, Chicago counted roughly 400 ethnic Japanese among its residents. As a result of Executive Order 9066, which led to the forced removal and mass incarceration of 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry along the U.S. West Coast, from 1942-1945 Chicago welcomed some 20,000 Japanese Americans both resettled from various concentration camps and returning from war.

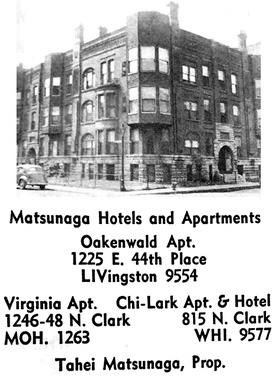

While the United States War Relocation Authority advised relocatees to not congregate into ethnic enclaves as had been priorly established on the West Coast, but rather disperse and assimilate into greater society, a combination of the sheer volume of resettlers combined with the principles of chain migration led to the formation of two mid-century Nikkei enclaves in Chicago: One straddling the South Side’s Oakland and Kenwood neighborhoods near 43rd and Ellis, and the other in heart of the Near North Side, centered at the corner of Clark and Division.

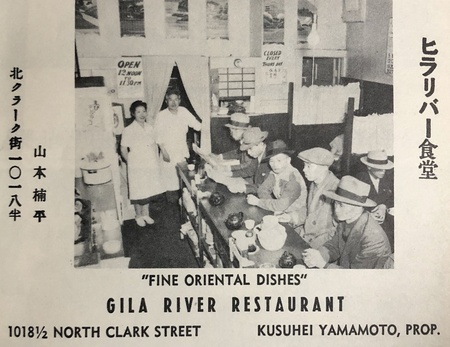

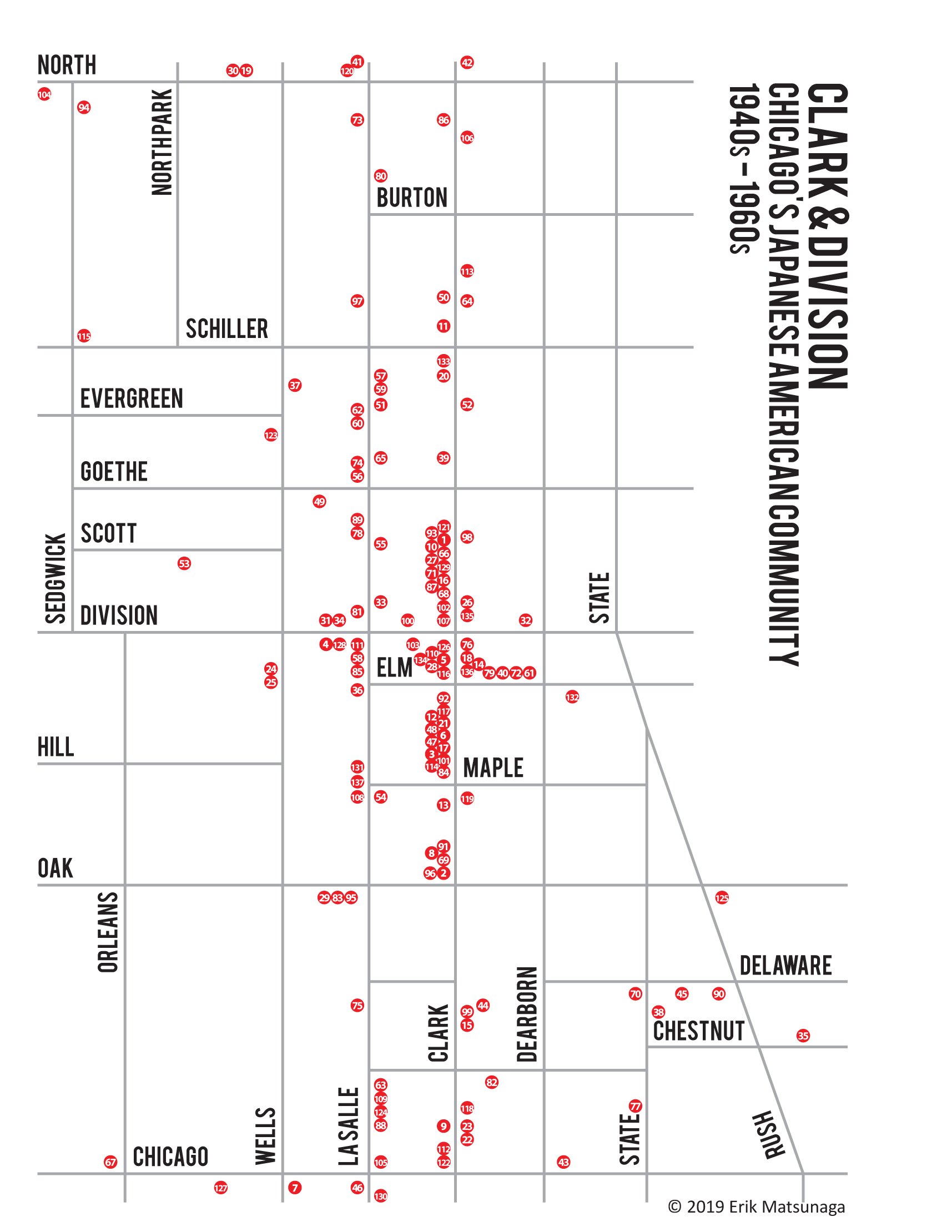

With over 200 Japanese American operated, run, and/or frequented establishments in the neighborhood over the course of two decades and thousands of residents living within the vicinity, it would be safe to say Clark and Division could have been considered one of two simultaneously existing Nihonmachi, or Japantown neighborhoods in Chicago during the wartime period as well as one of four extant in the United States. Two other Nikkei neighborhoods had been long established in Denver and Salt Lake City, whose sizable Japanese American communities had not been evacuated and who had also received resettled populations.

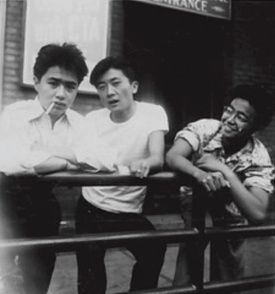

Clark and Division was a high density neighborhood of single occupancy hotels and tenements, mixed with street-level businesses. Situated in something of a “no man’s land” between the wealthy Gold Coast to the east and the poorer district of Old Town to the west, Clark Street had developed a reputation for vice with numerous night clubs, bars, and gambling establishments. For many former West Coast Japanese Americans resettled from camp, while they may have found their newly acquired conditional freedom better than incarceration under armed guard in barracks-strewn desert land, such bustling, crowded, and immoral inner city life was often utterly foreign and disturbing.

As the Chicago Nisei came of age, they established careers, stabilized financially, married, and began building their own families. Combined with urban renewal projects razing entire blocks near Clark and Division, advanced education and professional wages afforded them the opportunity to leave the congested environs of the Near North Side. Many, though by no means all, migrated three miles up Clark Street to the Lakeview neighborhood, in the area surrounding Wrigley Field. In the ensuing years, this community would develop a visible Japanese American presence.

Among entities that followed the migration from Near North to Lakeview were Diamond Trading, Toguri Mercantile, Triangle Camera, LaSalle Photo, Frank’s Watch Repair, Chicago Shimpo, Tom’s Standard Service, Aiko’s Art Materials, the Japanese American Service Committee, Nisei Lounge, Chikaraishi Optometry, Jiro Yamaguchi Law, Harry Omori Dentistry, York’s Grocery, Tenkatsu Restaurant, Matsuya Restaurant, Miyako Restaurant, and Johnny’s 3-Decker Sandwich Shop. Over a hundred other Nikkei entities would eventually establish or re-establish themselves in Lakeview over the course of thirty years from the 1960s-1990s, making that neighborhood Chicago’s last unofficial J-town.

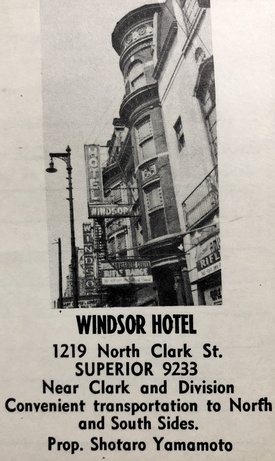

Near North in the early 21st century is a fairly wealthy community. While some historic buildings remain within a stone’s throw of Clark and Division (the Mark Twain Hotel, ca. 1930, still anchors the southwest corner), nary a one makes reference to former Japanese inhabitants or the extensive Nikkei community that once quietly thrived here for the better part of two decades as a result of America’s wartime hysteria. Though a few entities founded in the 1940s Clark and Division neighborhood remain in legacy as of 2019, they have changed hands multiple times across generations and no longer reside on the Near North Side.

This article is not meant to be an exhaustive history. It is a glimpse into another time, a neighborhood extinct, an offering to the ghosts of resettlement and a tip of the hat to those who toiled relentlessly to drive our Japanese American community onward and upward in spite of starting over from scratch. Despite the seedy nature of Near North’s history, one can glean through the following first-hand accounts that in many ways it was a magical place to grow up, in some aspects a tiny village plopped into the bustle of city life, where everyone knew everyone and looked out for each other.

Clark and Division was the first stop for my Nisei grandparents in 1945, when they resettled in Chicago with my infant father. They first resided at the Chi-Lark Apartment & Hotel at 815 N. Clark, toward the southern end of the neighborhood, near Chicago Avenue. The Chi-Lark was operated by Issei businessman Tahei Matsunaga, unrelated to us but like my great-grandparents an immigrant from Kumamoto, also a former Gila River incarceree, and a pre-war family friend from California.

“We were all in the same boat, at Clark and Division,” I remember my grandmother once telling me. “It wasn’t easy. But gee, it sure beat being locked up.”

* * * * *

The following accounts, from former residents, offer personal insight into both relocating to, and growing up in, the Clark and Division neighborhood. I thank all who took the time to share their experiences.

Special thanks:

Tonko Doi, for procuring recollections from Mototsugu “Junior” Morita and David Toguri.

Elizabeth B.J. Fukawa & Tyree Momii for referrals to additional former residents.

Ryan Yokota, Director of the Japanese American Service Committee Legacy Center Archives, for organizing multiple decades’ worth of community directories for address mapping.

Mike Takada, CEO of the Japanese American Service Committee, for allowing and encouraging continued research at the JASC.

* * * * *

Mototsugu “Junior” Morita

The first twelve years of my life were spent on an apple orchard at the base of Mt. Hood in Oregon, the next three and a half years in the isolated internment camps in California and Idaho.

Needless to say, moving to Chicago was an eye opening experience to this very naïve country boy. The area around Clark and Division Streets was not the kind of place that a typical American family would move to in order to raise a family with upwardly mobile aspirations.

That stretch of Clark Street starting a little further north of Division and south to the Chicago River was referred to by some as “Honky Tonk USA.” Conventioneers whose tastes were not as refined as those attracted to Rush Street would be drawn to the entertainment venues appealing to the baser instincts of man. Bars, night clubs, burlesque clubs, gambling houses, and houses of “ill repute” were interspersed among the more respectable establishments.

The influence of strong family value, having responsible adults present, and the need to help support the family kept me busy enough not to succumb to all the flash surrounding me. Although places like “Talk of the Town,” “Casablanca,” “McGoverns,” “Liberty Inn,” and “Post Time” did pique my interests and I have to admit seeing some of the “heavenly bodies” did help me pull some respectable grades in the anatomy class in dental school…

When I attended Northwestern Dental School, I lived in an apartment with no air conditioning where my room window opened to Clark Street right above the entrance to “Anchor Club,” a bar owned by a Hawaiian Nisei. My windows were always open on hot summer nights. Studying in the wee hours of the morning, I would have entertainment furnished by the bouncer booting out unruly customers in various stages of intoxication. “Casablanca Night Club” across the street was where street walkers were sometimes seen playing their trades. I was never bored, but often distracted.

The Resettlers Committee, the precursor to the Japanese American Service Committee, was across the street when I lived in LaSalle Mansion at LaSalle and Maple Streets. My first jobs in the city as a high school student were found through this agency, when Corky Kawasaki was directing the place. I remember attending parties and meetings for young people in that facility.

What made Clark and Division and the immediate area around it a comfort zone for me was easy access to the things that were familiar to me such as Japanese-owned restaurants and grocery stores offering prepared as well as fresh Japanese foods, a barber shop, a shoe repair shop, dry cleaners, Nisei dentists, doctor, optometrist, jewelers, travel agent, accountant, and employment agent. Also present were many familiar faces of fellow students and their families, all of whom had been confined in the camps.

Entertainment venues like the five movie houses: Windsor, Newberry, Plaza, Surf, and Esquire; a Penny Arcade; Gold Coast Pool and Billiard Hall; and a bowling alley were all within walking distance. For those who wanted intellectual stimulation, a half block away from my house was the famous Newberry Library and Washington Square Park, otherwise known as Bughouse Square, where soap box orator would expound on their areas of expertise nightly.

Clark and Division may not have been what most people would consider a desirable place to live, but for me it was my home for thirteen years, from 1946-1959. I have fond memories of it and it was my community, especially the confectionary shop, Ting-a-Ling. Betty and I shared many a coffee and apple pie ala mode, during our courtship, when she hopped off the subway train at Clark and Division on route home to the North Side from her first teaching position on the South Side. Actually, it was my apple pie and Betty’s coffee . . . she paid! She was working, I was a poor dental student.

* * * * *

Elsie Tanabe Yonamine

I was a member of the Windsor Theater’s Roy Rogers Fan Club. That allowed me a 10 cent admission price on Sundays. Since my mom had given me 31 cents for admission and popcorn, I had money to spare! And I would buy Plastic Wonder Bubbles on the way home. Such joy!! Life was fun for a little kid in those days. 58 West Elm Street is where we lived. The apartment was just three doors down from the Hawaiian Isle bar. The brick wall was painted over with a hula dancer – the original wall art which is so popular now!

In the summer, a bunch of us played Cowboys and Indians, although nobody was an Indian. The girls wanted to be Annie Oakley or Pistol Packin’ Patty. The boys had many more choices: Buffalo Bill, Tom Mix, Roy Rogers, Gene Autry – all heroes in the movies at the Windsor Theater. Every once in a while, the theater put on Fifteen Cartoon days – way better than today’s Avengers or Star Wars or other superhero movies, because we had no other entertainment besides our radios at home. We ran all around the block surrounded by Clark, Division Dearborn, and Elm Streets, laughing and shouting to our hearts’ content.

Another favorite pastime was roller skating on the old fashioned clip-on skates with a key you hung around your neck. I still have a photo of Takako on her skates, which I probably took with the Kodak Brownie camera my parents got for me on my tenth birthday.

Summer also meant a Sumo tournament held in some alley nearby. I wasn’t interested, so I don’t remember the details.

A lot of us Japanese kids went to Elm LaSalle Bible Church, which was just a block away. Our folks were Buddhist, but they figured any church was better than no church, so off we went. We joined Daily Vacation Bible School and loved the crafts and games at recess. In the summer, the church ran a day camp for two weeks which was also fun for us, especially when they took a busload of us to a faraway public swimming pool.

I joined the Pioneer Girls (sort of like Girl Scouts) and still remember the song and the pledge. In 7th or 8th grade, Pat, Taka, and I would go to Ting-a-Ling (an ice cream & candy store) instead of Pioneer Girls, our parents none the wiser. That was the extent of our secret pre-teen lives! As we grew older, some of us joined Christian churches and others went to Midwest Buddhist Church.

We all attended Ogden School, first on Chestnut Street, and later in its current location – I remember carrying textbooks from the old school to the new one on moving day. Nowadays, using kids like that wouldn’t be allowed. The best thing about the new Ogden School was the library – I remember checking out The Diary of Anne Frank – wow, what an education! When I was in high school, my friends and I went to see the play.

I usually walked home for lunch, but sometimes we went to the Lawson YMCA and bought mashed potatoes and gravy with a roll for 12 cents. Such luxury! We learned to swim at the McCormick YMCA – the greatest treat was a candy bar from the vending machine afterwards. That was 70 years ago – now, after exercise class, I love to go to Cheesecake Factory, absolutely negating the good effects of physical exertion!

In those days, we lived in old, cramped apartments with shared bathrooms, but we didn’t care because we had family and plenty of friends. The streets were safe and most of our needs could be taken care of right in the neighborhood – mothers could send kids out to the store to pick up milk or bread; our doctors, dentists, hair salon, cleaners were all nearby. So simple – just a short block away. No need for a car. The Loop was a quick ride on the subway or bus.

No play dates, no texts – just go outside and see who else is around. So simple!

* * * * *

Elizabeth B.J. Fukawa

It’s so much fun looking over the names on that list, and interesting to see how many branched out to other areas of the city, and how some just disappeared. My father owned and operated Frank’s Watch Repair, first at 1168 North LaSalle Street and then 1162-1/2 North Clark Street in the Clark and Division neighborhood. He later moved the shop to Lakeview.

All I know about the LaSalle Street shop is that it was tiny, and had a back room separated from the shop by a curtain. The back room housed a refrigerator and freezer that belonged to a restaurant and every once in a while, one of the employees would breeze in with a “Gomenasai” or “Sumimasen,” pass through the curtains, and emerge with a huge fish on his shoulders. I always loved that visual.

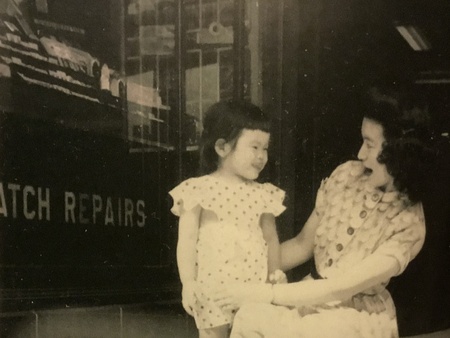

I know my mother was pregnant with me at the time, but I believe we had moved into the Clark Street address before I was born, or shortly thereafter. I do have some shots of me mugging for the camera with my mom at the Clark Street address, and I have a photo of my dad at his bench.

I used to spend a lot of time heading down the subway stairs and emerging on the opposite side of the street to visit Excel Food Mart, owned by Kevin Kaneko’s uncle. I remember wooden casks filled with whatever fermenting paste was used to make the takuwan and uri; nothing in a jar ever came close to their product. Besides running the market, the Kaneko family owned the building I used to spend some of my after school hours in, at 1020 North Clark Street, as Kevin and I were the same age.

I remember various restaurant adventures, but through such a young filter; we moved out of the neighborhood when I was seven. I wish I had been older so my recollections could be clearer.

It just boggles my mind to see how far reaching its influence extended, geographically and institutionally, from retail to service to real estate; it’s like a family tree of an entire community!

I’m just sorry the Issei generation have passed on and that even the Nisei are of advanced age, which is fine if their faculties are still sharp; I’m sure the stories they could tell would be amazing and enlightening.

|

|

|

© 2019 Erik Matsunaga