Tule Lake Committee chair Hiroshi Shimizu attended his first Tule Lake Pilgrimage in 1994, clutching a folder of papers written in Japanese. He had seen an article announcing the pilgrimage in the Hokubei Mainichi, the former Northern California daily newspaper that his father, Iwao, not only helped to start but also served as its Japanese editor for nearly 25 years. Hiroshi was curious about the place where he had spent time as a child, even though he had always considered Topaz his “home camp” since that’s where he was born. Still, not knowing much about Tule Lake he was somewhat drawn to the place where he and his parents had been moved after Topaz, and equally curious about what was in the folder he had saved among his father’s papers.

In 1943, Tule Lake was the camp chosen out of the ten incarceration centers run by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to be designated the “segregation center” for those who either refused to sign or signed “no-no” to the so-called “loyalty questionnaire” numbers 27 and 28 that asked if Nisei were willing to serve in the military and swear unqualified allegiance to the US.

Even fifty years later at the time of the 1994 pilgrimage, Tule Lake survivors were suffering from the disgrace of being labeled “disloyal,” and many still felt the sting of shame associated with having been held there. The government, and even fellow Japanese Americans, had managed to stigmatize those who had complicated and various reasons for choosing to answer “no-no.” Among the many sent to Tule Lake were those Japanese-speaking Issei immigrants who felt ties to the country in which they were born. Others were American citizens who protested being incarcerated without due process of law. Fluent in Japanese having spent 14 years in Japan as a youth, American-born Iwao Shimizu was sent to Tule Lake because of a unique situation (as his son was soon to find out).

Early on during the 1994 pilgrimage, Hiroshi was lucky enough to meet someone who could make out what his father’s papers contained. Yasushi Ishii, a fellow pilgrim and native Japanese speaker, peaked Hiroshi’s curiosity as they leafed through them together, and Hiroshi clearly remembers the words he heard. “This is interesting,” Ishii said. It turned out that among the sheets was what appeared to be a transcript of an overseas radio broadcast that had something to do with “ships.” Remembering that their family had a shortwave radio years later after they resettled in San Francisco, Hiroshi concluded that the radio had eluded confiscation while his father was imprisoned at Tule Lake. The banned box made it possible for his father to transcribe broadcasts to share with others seeking some word from the country with which America was at war.

Thus began Hiroshi’s journey to find out everything he could about his father’s role as an early renunciant (U.S. citizen who renounced his citizenship during WWII) and to probe into the details of the complicated segregation story as it affected his family. WRA records showed that Iwao and his wife, Fusako, were first sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center, then to the Topaz camp in Delta, Utah, in 1942. While there Iwao, a former newspaper editor, helped to start the camp newspaper, Topaz Times, as its Japanese editor.

Unlike his newspaperman father, Hiroshi was no journalist but he managed to use every investigative tool to find out more about his fascinating parent. Hiroshi discovered his father’s name on an unusual list of persons who were “invited” by the Japanese government to return to Japan in exchange for American citizens being held there. His father initially declined, but his grandfather, Iwajiro, who had been arrested the day after Pearl Harbor and sent to Department of Justice camps at Missoula, Lordsburg, and Santa Fe, was angered at his forced treatment and wanted the family be reunited in Japan. At his father’s insistence, Iwao finally agreed to the exchange, and the family headed to New Jersey to wait for the US transport ship, the MS Gripsholm, to take them to Japan. Fortuitously, a change in the number of passengers willing to board the ship caused them to be transferred to the Tule Lake Segregation Center near the California-Oregon border.

Hiroshi discovered documents that indicated his father’s bilingual abilities made him an important resource for first-hand information about life at the Tule Lake Segregation Center. Not only did the elder Shimizu transcribe shortwave radio broadcasts, but he also kept a daily journal during the turbulent time at Tule Lake when a general strike broke out, martial law was instituted, and four members of the inmate-formed Negotiating Committee were put in the stockade for their role in the disturbances. Iwao was among four men appointed to replace the original members of the Negotiating Committee, and he, too, was arrested and served time in the stockade from December 17, 1943 to February 9, 1944.

While inside the infamous “prison-within-a-prison,” Iwao kept detailed notes (all written in perfect Japanese script) of how prisoners were being mistreated while being held in unsanitary conditions, and physically threatened, robbed of their valuables, and sometimes even deprived of food or water. As recounted in The Spoilage, the study conducted by Dorothy Swaine Thomas and Richard S. Nishimoto, Shimizu (described in the book multiple times under the pseudonym of Kazuo Yokota) was considered among the influential leaders who attempted to quell the dissension between the detainees and the administration. After his release Iwao played a leading role in working with factions to end the general strike. When the clashes settled down, he eventually became a teacher in the Third Ward at Tule Lake.

Iwao’s leadership role did not end at Tule Lake. In March 1946, the family was transferred to the DOJ camp at Crystal City with about 300 other Tule Lake renunciants who had been rejected for release and scheduled to be deported despite the fact that the war had ended.

At Crystal City Iwao took on the official position of “group spokesman” for the Japanese-speaking people at the detention center that by then also held Japanese, German Latin Americans, German aliens, and German American Bund (an established pro-Nazi organization) members. His job involved helping his fellow detainees find sponsors in order to stay in the US, working closely with famed attorney Wayne Collins, who had filed a lawsuit to prevent deportations. Some 600 Peruvian Japanese had been deported before Collins got involved, but he subsequently helped keep more than 300 Japanese Latin Americans from being expelled and secured permanent residency for them. Later, Collins would also be principally responsible for assisting more than five thousand renunciants file affidavits to legally regain their citizenship after having renounced under wartime pressure.

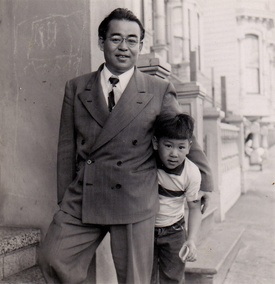

When they were finally released in September 1947, the family, which by then consisted of Hiroshi and two sisters, Michiko and Junko, managed to find a place to live, thanks to a family friend, in the attic of a San Francisco hotel their benefactor owned. Two more siblings, Ann Kazuko and Donald Akira, were born soon after. Many years later, Hiroshi would learn that the Kirkland Hotel, their makeshift home during the difficult resettlement period, had a reputation as a house of prostitution.

In 1948 Iwao joined with a colleague to form the Buddhist counterpart to the oldest Japanese American newspaper in Northern California, the Nichi Bei Times. Iwao devoted the rest of his life to being Japanese editor, then president, of Hokubei Mainichi, the newspaper conceived by the Buddhist Churches of America (BCA). Both newspapers flourished for many years but were forced to close in 2009. (Shortly after, the Nichi Bei Times was reorganized as a nonprofit organization and returned as the Nichi Bei Weekly.)

Like most Sansei children, Hiroshi spoke little to his father about the turbulent camp years. When Iwao died in 1976, Hiroshi had not yet begun his research, and today he reflects back that he “didn’t know enough to ask the right questions.” However, since that first pilgrimage to Tule Lake, he has sorted through innumerable family papers and photographs, combed through the National Archives, and spoken to countless friends and acquaintances to glean anything he could about his family’s and Tule Lake’s complex history.

Even more remarkable, since attending every Tule Lake Pilgrimage since 1994, Hiroshi has assumed the demanding role of chairing the Tule Lake Committee that puts together the popular four-day event every other year, a position he has held for the last 15 years.

Like his father, Hiroshi’s leadership role on behalf of the Japanese American community has gone far beyond Tule Lake. Recently, Hiroshi assumed the position as co-chair of the Crystal City Pilgrimage, which will hold its first official event from October 31 to November 3, 2019. He has also served as planning chair for the Bay Area Day of Remembrance from 2007 to 2017, president of the San Francisco JACL from 2006 to 2010, board member of Kimochi, Inc., and still serves as board president of the Japanese American National Library.

Both Iwao and Hiroshi took on leadership duties with little fanfare and have committed their time and energy to both Japanese and American concerns while still managing to find outlets in other interests. At Tule Lake, Iwao devoted much of his spare time to the advancement of judo and even helped build a dojo there, an effort he wrote was “at the heart of our national spirit inside such a camp.” He had also been an accomplished golfer from as early as 1930, and even won several corporate golf tournaments scoring in the mid to low 80s. Although Hiroshi never picked up his father’s love of judo or golf, he has managed to find his retreat in jazz clubs and on the tennis court.

Few share the dedication to community as this father and son who were once branded disloyal. At one time narrowly escaping deportation to Japan, both have managed to thrive in a country that once considered them the enemy. Were it not for the legacy of Iwao Shimizu as collected and shared through his eldest son, Hiroshi, much of that dark history of incarceration and renunciation would lie forever buried in the shadows.

© 2019 Sharon Yamato