Japanese people don't know about Japanese people

I have been in America for 28 years. During that time, I have interviewed many Japanese Americans as a writer. I am also interested in why people in the same situation as me decided to come to America and what pushed them to make it happen, so I have spoken to many Shin-Issei living in America. And I always think that people from Japan don't know much about Japanese Americans. That Japanese Americans were sent to internment camps during the war and were forced to start over from scratch after the war. Even Japanese people living in America are like that. Japanese people who live in Japan and come to America for tourism or business trips hardly know anything about Japanese Americans. That is why I have been trying to tell people about Japanese Americans and Shin-Issei in America through Discover Nikkei, an online medium that can be viewed from anywhere in the world. The other day, I felt that my work had paid off. A man named Yohei Inoue, a social studies teacher at a public school in Shiga Prefecture, Japan, read my article and sent me an email.

The email said, "I'm interested in the Japanese community in Venice that you wrote about in your article." I had written about three communities where Japanese people once lived: Terminal Island, the Crenshaw District, and Venice, a long time ago. After learning that his grandfather had worked in Colorado before the war, Inoue became interested in Japanese people in America as he researched them. He had already visited Little Tokyo and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, but he wanted to go to Venice on his next visit. I was very happy that a Japanese person was interested in Japanese people and the Japanese community in America, so I agreed to be Inoue's guide and we decided to visit places related to Japanese people around Los Angeles together on a certain day in mid-September.

Venice to Terminal Island

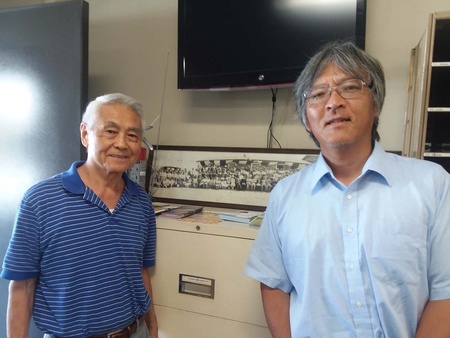

At 9:30 in the morning, I picked up Mr. Inoue at a hotel downtown, and our first stop was the Venice Japanese Community Center, where I was greeted by the chairman, Mr. John Ikegami, with whom I had made an appointment in advance.

According to Ikegami, the center has a membership of 1,500. "Not only do we have a Japanese language school attached to the center, we also offer classes in Japanese culture such as calligraphy and flower arranging, which are very popular. The most difficult part of running the center is raising funds. Also, as generations go by, the number of pure Japanese people is decreasing due to intermarriage with people of other races, so we are always conscious of expanding the target audience of the center," Ikegami said.

Before the war, Japanese people who were based in Venice were engaged in cultivating celery. There is no sign of the celery farms now, but Japanese people grew celery and shipped it to the downtown market by rail. The remains of the railroad tracks remain as a promenade along Culver Boulevard, and I showed Inoue a look at them from the car while we were traveling.

After listening to his talk, Ikegami-san gave us a tour of the center, which has offices, classrooms, a gym, an auditorium, and other impressive facilities where members can immerse themselves in cultural, educational, and sporting activities, all made possible by steady fundraising.

After parting ways with Ikegami, we headed to Terminal Island. Before the war, there was a fishing village here, mainly made up of people who had come to America from Wakayama Prefecture. There were two elementary schools, one Buddhist and one Christian, and almost all the teachers and students were Japanese, so the children had a hard time understanding English when they went to school outside the island. However, after the war ended, the settlements that had spread out around Meguriguri were evacuated, and the residents were left with nowhere to go. Now, only a replica torii gate and a fisherman statue remain, and there is nothing else to remind us of the past. Inoue, who became a school teacher in Shiga, says that his roots are in Wakayama Prefecture. We spent a moment around the torii gate, thinking that it might not have been strange if his ancestors had immigrated to this place.

Finally, we went to a former Respect for the Aged care facility.

For lunch, we chose Bob's Hawaiian in Gardena, a Japanese Hawaiian restaurant. Bob's has been loved by regular customers since the previous owner, Kimi Sato, took over from the previous Japanese Hawaiian owner. There are certainly many Japanese people from Hawaii in Gardena. Inoue asked me, "Why do people come to the mainland from Hawaii?" and I told him the answer I had heard from someone before. "There are only jobs in Hawaii in tourism and the military industry, so I think many Japanese people who go to college on the mainland don't go back to Hawaii and stay here. Gardena was originally a community formed by Japanese people who were engaged in strawberry farming, so it must have been easy for Japanese people from Hawaii to live here." While we were eating, Inoue also told me why Kimi, the owner, came to America.

Our next appointment was at the Gardena Buddhist Church. I was interested to hear why John Ihara, the missionary there, chose to follow the path of Buddhism. "I used to go to the Buddhist church with my mother, who was born in Japan. However, it was difficult for my mother to understand what the missionary was saying (in English), so I tried my best to listen so that I could explain things to my mother in Japanese. As a result, I was drawn to the wonderful world of Buddhism."

At the end of the day, I took Inoue to the former Respect for the Aged Day facility in Boyle Heights near downtown. "One of the founders was a great man named Fred Wada from Wakayama Prefecture. It was opened as a senior citizen's home for Japanese Americans, but it was sold to a real estate company a few years ago. It was once a place that could be called a goal for Japanese Americans and Japanese people to retire in America," I explained. In the past, many people donated their money and time (volunteers) to keep it running. The Respect for the Aged Day facility is gone (the senior citizen's home itself remains, but it has been renamed and is run differently than before), but I wanted the social studies teacher from Japan who visited Los Angeles to realize how the survival of the Japanese community is based on the hard work of each individual. I wonder how it looked to Inoue.

© 2019 Keiko Fukuda