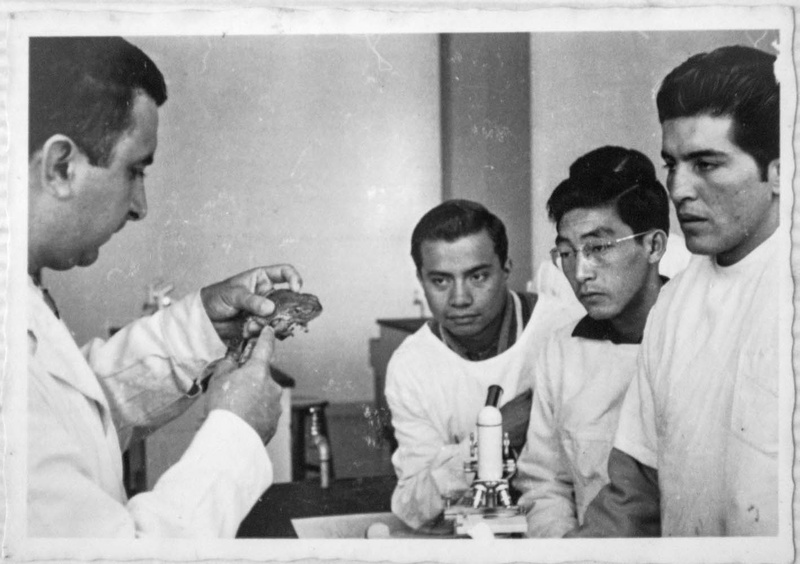

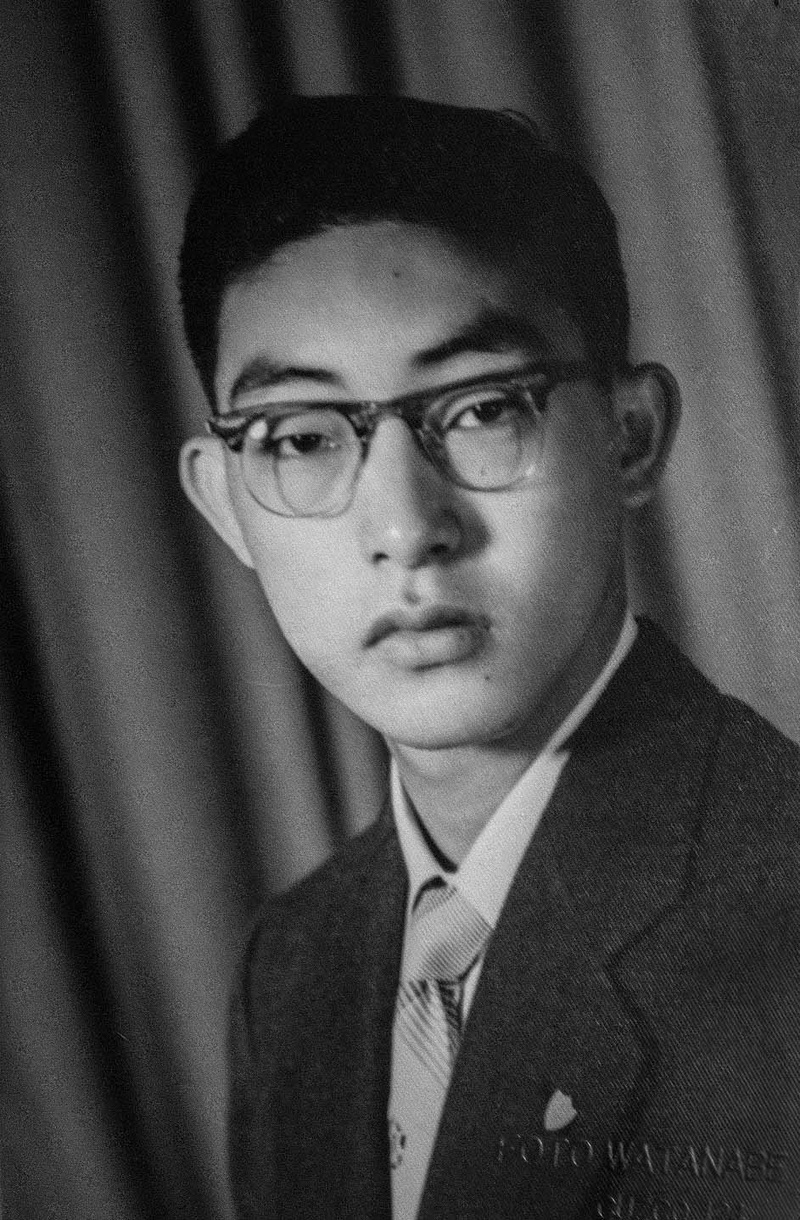

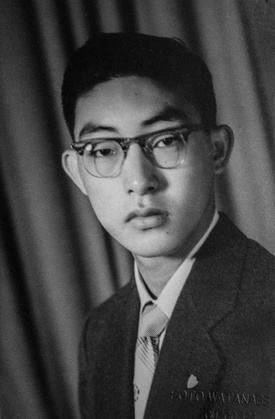

“This is how an artist must feel,” says César Tsuneshige while being photographed. It is a new experience for him to be the subject of a photo shoot. As a veterinarian, leader of the Nikkei community, and student of the history of Japanese immigration to Peru, he is used to dedicating his attention to others. The fact that the spotlight is now on him disorients him a little.

However, he also takes it as a recognition. It means that he has left his mark. It has been a long road traveled.

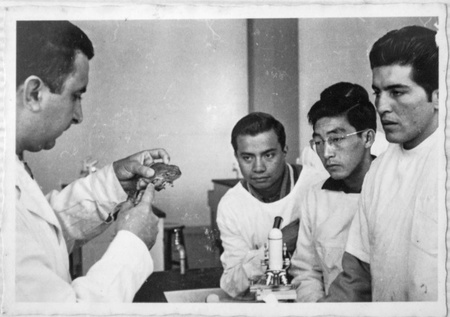

Seventh of eight children in a family of immigrants from the Yamaguchi prefecture, he inherited his vocation for service from his father Makoto, who was the doctor of the Japanese colony in Callao, where he has always lived. In a written testimony he remembers his father:

“They had no schedule, since in their urgent search, many times in the early morning they broke into the house. And although sometimes he was in the best of dreams, he never stopped assisting the patient.”

He attended at home, but also wherever he was needed. “Helping the sick on the farms was a major job, (they had to) travel in trucks in the darkness of the night, along a road of packed earth, on the way to the beasts of burden, where the dust and mounds made people jump and hit humanity, until we reach the adobe house.”

From his father he also inherited his desire for documentation. Archive everything. To leave a record, to not forget, for the future. He goes through his photo albums, looks back at the past, remembers his parents and siblings.

He remembers, for example, that during the war his mother Sadako had to sell her precious koto , a cause of great family distress due to the difficult economic situation they were going through. There is, however, a happy memory associated with her: when I accompanied her to the movies. “It was a prize,” he says.

He remembers with gratitude the second of his brothers, Roberto, because he helped him a lot with his studies.

He remembers that when he was two years old, two of his brothers were sent to Japan to study. No one could imagine that shortly afterward a war would break out that would separate the family forever. He never saw one of them again because he died young. He was reunited with his other brother more than 50 years later.

He remembers, above all, his father. They talked a lot. When he left home, he would find his father waiting for him when he returned. He told her what he had done, who he had been with. He liked to talk to him and he believes that his father liked to listen to the detailed account of his adventures.

It was not usual in those times for there to be that type of communication between austere Issei who preferred to express themselves with actions and children who obeyed without the possibility of reply.

He knows himself lucky for that level of connection with his father. “I have been lucky, it must be because I am the fifth (of the men), almost one of the pussys.” Confidence allowed him, for example, to confront his father: “Why do others have jidosha (car) and we don't?” “You don't reason,” he says now, as an adult.

His memories are not limited to family. When he was a boy, there was a large Japanese colony in Callao and César Tsuneshige has a mental map of the city at that time, full of shops and houses of Japanese families. You only have to mention a last name to tell where the family lived and what business they had. Everything is filed in your head.

DISCOVERING THE HISTORY

Sticking to the traditional question-and-answer format in a César Tsuneshige interview is like trying to store a river in a glass. Thus, it is best to dispense with any container and let the waters run their course freely.

One of his favorite memories, to which he always returns, is his tenure as president of the La Unión Stadium Association (AELU) in the early 1990s, a critical time for the Nikkei community.

At the height of the dekasegi phenomenon, there were very small people and very big people in the stadium. Those in the middle were missing: the young and the middle-aged. They were in Japan working. The thing was so serious that it reminds us of a sports competition in which there was only one athlete in the race, competing with herself because she had no opponents.

It was in this difficult context that César Tsuneshige, as president, managed the construction of the elevated water tank, a work that was decided upon due to complaints from members about the hygienic services.

He knocked on several doors. One of them was that of Inca Kola, which despite the difficult situation in the country collaborated with a significant sum. The situation allowed him to learn about a little-known story. Once, he summoned the AELU leaders, including the founders, to say that he had received a proposal from Coca-Cola to enter the stadium. The elders informed him that during the war Inca Kola was the only company that helped Japanese businesses, refusing to bow to the anti-Japanese sentiment of the time.

Thus, out of loyalty to Inca Kola, it was decided not to accept the proposal of the then competition. As a sign of gratitude, César Tsuneshige always leaves flowers on the grave of Isaac Lindley, son of the founders of the Peruvian soda.

The Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) also contributed to the construction of the water tank. Elena Yoshida presided over the APJ and she was important not only because she managed and concretized financial support for the project. He was also one of the people who stimulated César Tsuneshige's interest in the history of Japanese immigration to Peru.

Just as he learned about the relationship between the colony and Inca Kola during the war thanks to the stories of the elders in AELU, in APJ little by little he began to learn about the origins of the Nikkei community through directors such as Elena Yoshida or Gerardo Maruy. Years later he was president of APJ.

LUCKY MAN

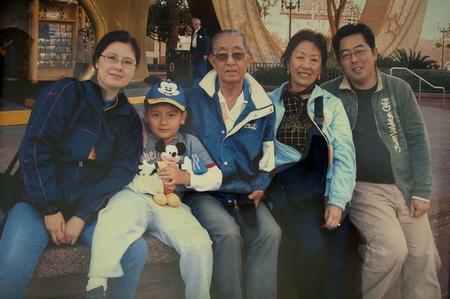

In 1990, César Tsuneshige visited Japan for the first time. More than half a century later, he was reunited with the brother his father had sent to Yamaguchi to study. He had a tough childhood, going from house to house, raised by aunts. However, he had reached old age with an established family. He had a comfortable and comfortable life.

Don César's parents could not return to their country after migrating to Peru. There was never a reunion with the children who were sent to Japan. For this reason, he made a point of letting his brother know that his parents always thought about him, that his mother cried for her son who was far away, that the war changed everything.

Like his brother in Japan, he also already had a life made up, with his wife Lucha and his children César and Patricia.

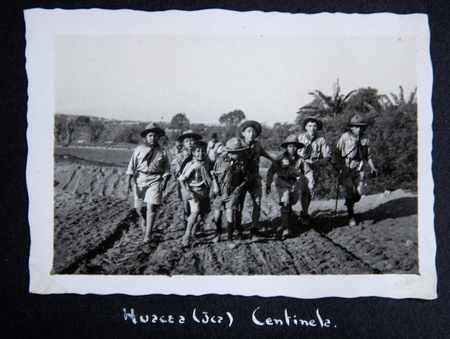

With his wife he managed to overcome difficult times, like when he was held hostage, with hundreds of people, by a terrorist group that took over the residence of the Japanese ambassador in 1996. He was locked up for five days. The foundations provided by his parents' upbringing and the scout movement that welcomed him as a child gave him “moral strength” to resist.

Of Luisa, with whom he was married from 1968 to 2011, when she died, he highlights “her determination, her character, her strength.”

“I've been lucky to have a good family,” he says. From his father he learned “the spirit of serving” and highlights the kindness of his mother.

A lesson that his father instilled in him and that he always remembers is that punctuality is non-negotiable. “You have to be punctual, because you respect yourself and you respect the schedule of others,” he said. “But dad, the other one is late,” César replied. “No, you have to arrive.”

Its main capital is emotional ties. What he is most proud of is “having had a good family, good friends. To have contributed something, even with a grain of sand, to the community (Nikkei). "To have had good teachers in scouting, who left foundations in extremely difficult times."

The happiest day of his life was the day of his marriage.

A GRANITE THAT LEAVES A MARK

Dr. Tsuneshige is currently reading a work on the life of Fidel Castro that was given to him by the Cuban ambassador, whom he met during the celebration of the 115 years of Kumamoto immigration to Peru.

He never lacks the company of a book. An essential element in your life. “It's not a question of money, it's a question of leaving something behind. The best thing one can leave behind are books. Leave something written that lasts. Without wanting to, one transcends time. Without being more than a grain in this world, you leave some kind of mark,” he says.

Life is like a wide network of connections that is woven throughout an entire existence. In your case, you have seen how that chain of links has marked you. A person he helped in the past reappears in his life much later and gives him a hand. What goes around comes around. Therefore, he always emphasizes the importance of gratitude and reciprocity.

That his works are collected in publications abroad, that he is considered a reference in the history of the Nikkei community or that he is interviewed in recognition of his career "are satisfactions," he says, "that cannot be bought with money."

Finish the photo session. Now you know how an artist feels.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 117, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2018 Texto y fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa