Uwajimaya, run by Fujimatsu Moriguchi and Sadako, a married couple with three children, was always crowded with Japanese people, as it was a store. The children were loved and looked after by these adults, and they grew up in a life similar to that of a rural Japanese community. The reason people gathered there so easily was largely due to Sadako's kind personality, who would kindly look after any fellow Japanese person in need.

Fujimatsu's younger brother, Saisuke, who was called over from his hometown in Ehime Prefecture, died soon after due to poor health, but the business was prosperous enough to hire staff. His eldest son, Kenzo, attended a local elementary school and then a Japanese school. From the age of eight, he helped out by arranging the products and serving customers.

It was common for Japanese who immigrated to America to leave their children with their parents in their hometown in Japan to be raised there for a while. This was because they wanted their children to receive an education in Japan, or because it would be difficult to care for them due to work or business reasons in America.

In 1941 (Showa 16), the Moriguchi family's eldest daughter, Suwako, was sent to live with her aunt in her hometown in Ehime Prefecture. Sadako set off alone, accompanied by Suwako and her two-year-old third son, Akira, by boat to Japan. They arrived at the port of Kobe, crossed the Seto Inland Sea into Ehime, and from there took the Yosan Main Line (now the Yosan Line) to its terminus at Yawatahama Station, then traveled further along the coast to finally arrive at the village of Kawanazu, where the Moriguchi family home was located.

She left Suwako with Kame, Fujimatsu's younger sister, who was unmarried and stayed at home, then turned around and returned to Tacoma with Akira. After this, when war broke out between Japan and the United States and the country was in a state of war, it was no longer possible to travel between the two countries, and it was only after the war that Suwako was able to join her family in America.

On February 19, 1942, just over two months after the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, President Roosevelt of the United States issued a presidential decree that designated people of Japanese ancestry as enemy aliens (race) and ordered them to evacuate from the Pacific coast and other areas. However, when it became clear that this was impossible, they were sent to internment camps set up in seven different states and isolated there.

On Sunday, May 17th and the following day, 879 Japanese Americans from Tacoma's Japantown and other areas were loaded onto trains at Union Station and taken by rail to the Pinedale Assembly Center in Northern California, where they would spend the sweltering summer before being taken again to the Tule Lake internment camp on the Oregon border.

Fujimatsu, Sadako and her husband, and their three children, excluding their eldest daughter Suwako, were also part of this movement. At that time, Japanese families were expected to live in poor conditions, but every family member was well-groomed and carried suitcases as they boarded the train. The Moriguchi family, including Sadako, who always looked neat and tidy, were probably no exception.

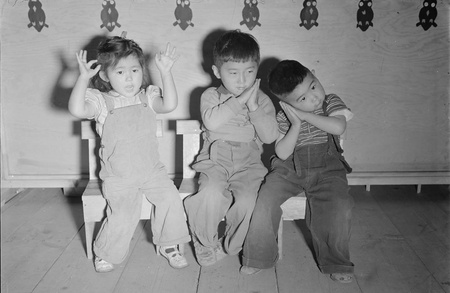

After a long journey with their children from Pinedale to Tule Lake, the family began their life in the internment camp. At the time, their eldest son, Kenzo, was 8 years old, Tomio was 6, and Akira was 3. Later, while still in the camp, their second daughter, Hisako, and fourth son, Toshi, were born, and just after the end of the war, their third daughter, Tomoko, was born.

Kenzo was the only one who remembered what happened at that time to some extent. He still didn't understand the meaning of being put in the camp, and he didn't feel any anger.

"I played a lot of games and enjoyed sports with my friends," Kenzo recalls now. Tomio also remembers playing with his friends.

As for Fujimatsu and Sadako, they rarely spoke about the war even after they left the internment camp. Fujimatsu was originally a strict person towards children and was not the type to talk casually. Sadako, who was usually kind to children, also rarely spoke about the war.

"She must have been worried. She may have thought that she had done something wrong, even though she hadn't," Tomio speculates about his mother's complicated feelings. However, Tomio remembers that once, some time after the war, Sadako let slip the following comment about her life in the internment camp:

"When you go to prison, you know when you'll be released (because there is a sentence), but with the detention center, I didn't know when I'd be released, whether it would be a year or 10 years, and that made me anxious."

(Titles omitted)

© 2018 Ryusuke Kawai