自由を求めた明治の女性 =「1年だけ」母との約束

2013年11月5日夜、聖市のイビラプエラ講堂は拍手と熱気に包まれた。今は亡きオスカー・ニーマイヤーと共に、連邦政府が贈る最高位の「文化勲章」を手にした大竹富江さん(99、京都、帰化人)は、その夜最大の拍手を浴びた。それは富江さんを、国民の一人として受け入れた伯国民の素直な賞賛の表れだった。翌日各伯字紙は「大竹富江は、ブラジル・ヴィジュアルアートを代表する最も著名な人物の一人」とこぞって報じた。

彼女ほどはば広くブラジル社会から敬愛された日本人女性芸術家は他におらず、しかも、今なお現役で21日に100歳の誕生日を迎える。意外と少ない日本語の記録を存命の間に残しておきたい、そんな思いで取材を始めた。

* * *

ジョゼ・ディニース大通りから徒歩3分。長男ルイさんが設計したカンポ・ベロ区のアトリエ兼自宅で、100歳の巨匠は今も週に3度キャンパスに向かう。

モレーナの家政婦に招き入れられアトリエを訪ねると、いつもの黒服姿で車椅子に座って記者を待っていた。「遠慮しないで、食べなさい。太ちゃん(アシスタント)、コーヒー入れてあげて。砂糖はいる?」。いそいそと自ら記者をもてなすと、自身もクッキーをつまみながら「それで、どんなことが聞きたいの」という表情でこちらを見た。

聞きたいことはたくさんある。でも、まずは無難にブラジルに来た経緯から聞いてみたい。そう言うと、富江さんは「任せて」とでも言わんばかりに、ちょっとしわがれた低音の力強い声で、原稿を読むかのように滔々と語りだした。

* * *

富江さんは京都の材木商の家に生まれ、当時の女性としては珍しい大卒(同志社文学部)だった。2年前に渡伯していた4番目の兄・益太郎さんを追って、1936年に23歳で当地を訪れた。

不慣れなポ語でも臆すことなくタクシーの運転手で生計を立てていた益太郎さんは、新たに貿易商を始めるため、満州で新聞記者をしていた弟をわざわざ呼びよせたという。それが5番目の兄で、「一番気が合っていた」ので、彼の来伯に便乗して富江さんは海を渡った。

息子には比較的自由にさせた母・中久保喜美さんも、6人兄弟の末っ子だった彼女には “普通の女” としての幸せを願った。母は「絵描きなんかになってどうするの。結婚しなさい」といって聞かなかったが、娘は「どうしてもいきたい。1年で帰るから」と約束して日本を出たのだった。

京都の良家に生まれただけに、「生け花習えとか茶の湯習えとか。女性の嗜みだといって一通り習いましたけど、じっと座って何かするって気持ちはなかった」と思い出す。着物を着た奥ゆかしい “深窓の令嬢” ではなく、お転婆娘だったようだ。

「今でも日本に帰ると、こんなになってしまう」と言って窮屈そうに肩をすぼめてみせ、「日本にいたら絵描きになってませんね。もう帰りたいとは思いません」ときっぱり言い切った。

特に日本の美術界は肩書きが絵の売値を左右する、かなり “独特” な世界だと聞く。

「こちらに来てすぐシナと戦争が始まって、戻れなくなりました」と、いかにも「仕方がなかった」かのように語る富江さん。「本当に1年で帰るつもりだったんですか」とたたみ掛けるように尋ねると、「分かりませんね。ずっと外に出て仕事がしたかったから」と冗談っぽくはぐらかした。きっと、もともと帰る気などなかったに違いない。

運命の分岐点は結婚出産=大事なのはファミリア

運命の分岐点はどこにあるか分からない――。富江さんと共に渡伯した5番目の兄は、来伯わずか1年後の1937年、日中戦争が勃発して召集が来て、わざわざ帰国して戦地へ赴き――そこで戦死した。

令状を受け取らなかったという4番目の兄・益太郎さんは当地にとどまり、聖市リベルダーデ区で製薬会社「ワカモト」を経営していた。益太郎さんを知る人々によると、恰幅のよい豪快な人物だったという。来伯当初はタクシーの運転手をしていたが、ポ語ができないため、客が指示する住所を知りもしないで車を走らせて、「そっちじゃない!こっちだ」など客に言わせて何とかやっていたという笑い話のようなエピソードもある。

益太郎さんが移住した1934年の日本は、軍国主義が年々強まり、共産主義者どころか自由主義的知識人に至るまで、反政府的な芽が厳しく摘まれていた時代だった。世界恐慌に続く昭和大恐慌、満州事変から五・一五事件、二・二六事件と国を揺るがす出来事が相次ぎ、軍部が大陸進出に向けて胎動を強めた不穏な時期だった。

「大学卒業しても仕事がなかった兄は、ブラジルはどんなところかと思って移住したみたい」と、富江さんは詳しいことはわからないといった風だった。

富江さん本人は「覚えていない」というが、次男のリカルドさん(70、二世)によれば、「ブラジルが軍政だったころ、母は軍政反対デモにも参加していた。僕もルイも熱心に活動していたので、一度つかまったこともある」との意外な一面を持つ。京都の伝統や保守的な雰囲気から逃れてきた明治の “ハイカラさん” らしい逸話だ。

富江さんが反軍政デモに参加していたくらいなら、益太郎さんも軍国主義や自由を縛る日本の風潮を嫌っていたことは想像にかたくない。日本にいたら徴兵されていた可能性のある彼もまた、自由を求めてブラジルへやってきたのかもしれなかった。

* * *

1939年に勃発する欧州大戦に向けて、当地でも戦雲が漂い始めていた。当地にとどまり兄の家で暮らし始めた富江さんは「戦争で絵描きになるどころではない」と一時その夢を横に置いた。

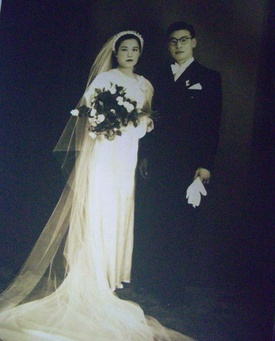

そして兄の同居人・丑夫さんと出会い、着伯した36年に結婚した。「それが5番目の兄とそっくりでね。ムイント・ボニートでボンジーニョだった」と当時を思い出してにんまり笑う。

「どっちがアタックしたんですか」と記者が突っ込むと、「そんなこと…」と100歳の “乙女” は照れて口をつぐんでしまった。大和撫子の逆を行くような人だから、きっと彼女がアタック(口説いた)したはずだ、と余計な推測をした。

そんなオテンバ娘も、38年に長男が誕生すると「人生にとってファミリアが大切か、仕事が大切かよく考えて、仕事は第二にしようと決めた」と振り返る。しばらくは妻、母としての道を選ぼう、と。身体に通っているのは、やはり明治女の血だ。

その頃、大竹一家はイタリア移民の工場労働者家庭が集まるモッカ区の一軒家に住んでいた。今のカンポ・ベロ区に引っ越したのは、ずっと後の62年だった。

* * *

大竹富江インスティチュートの館長、リカルドさんにも当時のことを聞いてみた。彼は忙しそうにバタバタと昼食から帰ってくると、本に埋もれそうな自身の事務室で、「自分自身にも子供に対しても、何でもきちんとするように求める厳しい母だった」と当時を回想した。

「『日本にはもう帰れない。ブラジル人になりましょう』といって、僕たちには西洋的な教育をした。僕らが通っていた学校も、キリスト教系だった。日本人は一人もいなかったね」。

* 本稿は、「ニッケイ新聞」(2013年11月20、22日)からの転載です。

© 2013 Nikkey Shimbun