La mayoría de japoneses llegaron a trabajar a las haciendas, y luego pasaron a las ciudades, en su mayoría de la costa, en su mayoría como comerciantes. Sin embargo, este proceso no fue homogéneo.

En el libro El futuro era el Perú, Alejandro Sakuda detalla que muchos inmigrantes aprendieron rápidamente varios oficios. Hablamos de peluqueros, joyeros, vidrieros y un largo etcétera. Luego, con el fin de la inmigración por contrato en 1923, otros japoneses llegaron a quedarse con parientes o conocidos, y fueron instruidos por ellos.

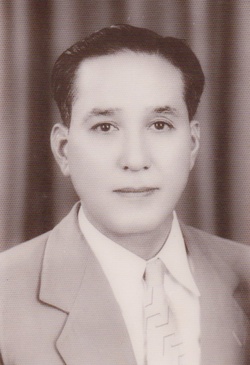

Un ejemplo de esta variedad es Gasumi Tokeshi, relojero con calidad de artista nacido en Kunigami en 1909, de precisión milimétrica en su trabajo y paciencia, sobre todo paciencia para una labor tan meticulosa. Lo conocí cuando era niño, yo tenía 8 años y él 80, siempre jovial y travieso, como seguramente sería en su adolescencia.

“Cuentan que era muy inquieto. Trabajaba como pescador y llevaba la cuenta de la pesca del día, por eso lo consideraban mucho aunque fuera muchacho. Pero su mamá se preocupaba por él, porque nunca se sabe si un pescador va a regresar. Por eso cuando un tío en el Perú pide un chico para que le ayude, su mamá lo envía para acá, en 1932”, cuenta su hija Eva. Por ese viaje Gasumi no participó en la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Fue el único de los hermanos que sobrevivió.

Aprendizaje de maestros

Ya en Lima, Gasumi trabajó en una tienda con su tío. Luego se hace relojero “con un maestro, como se hacía entonces, ayudando en el negocio, primero limpiando, ordenando, viendo cómo se hacía el oficio”, cuenta Amelia, otra de sus hijas. Esa era la única forma de aprender, con las prácticas tradicionales de enseñanza nipona. Tal vez por ello la cantidad de relojerías de japoneses fue creciendo, hasta ser este un oficio característico de la colonia.

Gasumi abrió su relojería propia en el jirón Cañete del centro de Lima, un local de techo alto con vitrinas pegadas a la pared, estantes de madera y trastienda tradicional. El trabajo era durísimo, requería de concentración y habilidad manual, además de vista fija y minuciosa. “Lo veía siempre con una lupa pegada al ojo, bajo una luz muy potente, agachado, muy concentrado”, recuerda Eva.

Muchas veces debía quedarse hasta la madrugada, pues “venían clientes de provincia, que se quedaban unos días en Lima, y le pedían a mi papá que por favor terminara en ese tiempo, y él se apuraba. Sus clientes eran sus amigos”, añade Eva.

Empezó así a hacerse de clientes, que regresaban siempre por la confianza que proyectaba, su honradez en el trabajo y su simpatía, de la que doy fe. Esta confianza era muy necesaria, pues le entregaban objetos valiosos. “Recuerdo las vitrinas llenas de relojes Longines, carísimos, que los clientes le dejaban sin ningún temor”, dice Amelia. Y poco a poco la relojería fue llenándose de tesoros. Cada noche Gasumi guardaba los relojes en la caja fuerte y en la mañana los volvía a colocar en las vitrinas. De esa manera les dio educación a sus seis hijos.

Artista de una época

Lo más difícil era reparar relojes de cuerda, “a los que a veces se les trababa una pieza, había que retirar la parte de la cuerda y repararla”, explica Amelia. Además, eran tiempos donde los relojes a prueba de agua no eran siquiera concebibles, entonces, “otras veces los clientes se metían al mar con el reloj puesto, para repararlos mi papá los desarmaba pieza por pieza para secarlos”, dice Eva.

Pero sí había lugar para las bromas. Gasumi se divertía con su compañero Eusebio Sipán, quien trabajaba por placer pues tenía propiedades y podía vivir de sus rentas. “El señor Sipán era un poco más tosco, él se encargaba de los relojes despertadores, que era un trabajo menos delicado. Eran muy amigos, pasaban bastante tiempo conversando”, cuenta Amelia.

De sus hijos Tito aprendió a reparar despertadores y Amelia a cambiar micas y reparar correas. Todo esto viéndolo trabajar, ayudándolo en sus vacaciones. Solo que el oficio estaba destinado a cambiar.

El paso de los años terminó con la relojería. En 1973, luego de pasar por una enfermedad, Gasumi debió cerrar el negocio. Lo convirtió en una dulcería. “Había menos clientes, porque aparecieron los relojes a pilas, y la zona se fue haciendo más peligrosa. Ya no era rentable”, comenta Amelia. Fue el fin de una etapa, pero Gasumi tuvo dos décadas más para compartir su sabiduría.

“Papá tenía manos delicadas, de artista. Siempre creyó que podía hacer algo diferente, creativo. Si no pudo hacer algo más fue por darnos educación a todos”, comenta Eva. Creo que un artista no lo es solo por su habilidad manual, sino por su sensibilidad, por su creatividad. Y Gasumi tenía mucho de las dos.

Su memoria para relatar episodios era fascinante, tanto que las investigadoras Wilma Derpich y Cecilia Israel lo entrevistaron para su libro Obreros frente a la crisis: testimonios años treinta, pues Gasumi se acordaba de cosas tan minuciosas como el precio del pan de cada año, y qué cosas podía uno comprar con un real. El maestro relojero se mantuvo activo hasta sus últimos días con la misma jovialidad y precisión, esta vez en sus palabras, pocas pero siempre atinadas.

“Dedícate a la música”

A lo largo de las décadas frente a la relojería, Gasumi recibió a muchos jóvenes como aprendices. Uno de ellos fue el recordado Luis Abelardo Takahasi Núñez, quien recuerda en sus memorias que fue Gasumi quien lo alentó a seguir su carrera musical. “Como relojero, eres buen músico criollo, dedícate a eso”, le dijo Gasumi con sentido del humor. Y no fue una mala sugerencia.

* Este artículo se publica gracias al convenio entre la Asociación Peruano Japonesa (APJ) y el Proyecto Discover Nikkei. Artículo publicado originalmente en la revista Kaikan Nº 73, y adaptado para Discover Nikkei.

© 2012 Asociación Peruano Japonesa