Read Part 4 >>

Stahl Family:

The Stahl family was one of the few families in the community that was of mixed race. Mr. Stahl, Earl, was a native of northern Louisiana, from rural areas around Shreveport. He was relatively typical for the region, the grandson of European farming immigrants-in his case from Germany-who had come to the US at the turn of the century in search of better opportunities.

The unusual thing about Earl Stahl was that, as a young architecture student at Tulane University, he became part of a growing interest that certain American architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and Albert Ledner had in the forms of traditional Japanese architecture, especially as evinced in the Buddhist temples: the blurred boundary between inside and outside, the use of wood and paper, the welcoming of natural light into interiors, etc. Earl was so intrigued by these aesthetic forms and by the cultural ideas they implied that he took it upon himself to spend a summer in Japan, just after completing his undergraduate architecture degree.

When he returned to New Orleans, he went to work as an architect and also taught at his alma mater, Tulane University. He continued in that vein of young American architects who were incorporating Far Eastern aesthetics into their work. In 1960-61, he returned to Japan for a full year to explore those forms further. He met and married Tomiko Sasagawa, who taught some of the Japanese language classes he'd taken.

The Stahls participated in the Nikkei community but perhaps always slightly different from the rest. For one thing, they were mixed race, bi-cultural, and for another thing they had not been marked by the experience of concentration camps. Tomiko had seen the war, of course, but from the other side: the threat of firebombing in Kyoto; the hunger and shortages after the rendition; the confusion of the Occupation and the changed political organization of the State, now without the Emperor as Emperor and a new constitution of western authorship in place.

She came to Lousiana with a different sense or experience of what being Japanese was, and was rapidly becoming, in the post-WWII period. She therefore had points in common with other Nikkei, but she also had experiences that were unique, or were part of a changed Japan. Even so, she, like other Issei, was comforted by finding a community of Japanese in a place as strangely new and different as Louisiana.

Being a language instructor, Tomiko Stahl taught Japanese at International House in downtown New Orleans; her students were often academics or persons interested in Japan for cultural reasons. She was the translator of the Japanese news on a daily program on Public TV called "International Dateline" which featured translators from all different nations, reading their capital's newspapers feature articles in English.

The three Stahl kids made friends and mingled easily with the other Nikkei kids. There was much less racism there against them as half-white than there was at school where they were harangued for being "Oriental" (indeed much worse terms were the more regularly used ones). But one noticeable thing was that racism was not exclusive to being "Oriental" in a "white" place like a private school in New Orleans.

The oldest of the Stahl's children, Anna, accompanied her mother on trips to visit the family in Japan, and there she noted that other children found her "whiteness" to be as strange as the New Orleans kids found her "Asian-ness." For the most part, her childhood in the 60s and 70s in New Orleans, meant being the "Cajun Nikkei" to the other kids, mostly Sansei, in the Japan Club of New Orleans.

Later, when relations shifted for Japan and the USA as nations, and economic partners in the later 1970s, Anna and her brothers Ian and Eli again found that the treatment they received changed. In the US, being half-Japanese came to mean being somehow "brainy," while in Japan there grew a trend of young women getting their eyes surgically "rounded" and their hair dyed, and always wanting longer legs. For better or worse, these observations still serve to keep it well in mind that racism's judgments and labels are not permanently or essentially attached to a person. Racism's targets change based on social and political realities, realities which themselves can change, or be changed, for the better.

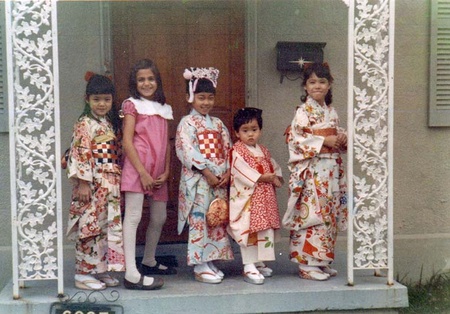

1969; Dressed in kimonos for a Japan Society event; Midori Yenari, ‘Ellen’, Yoshiko Uchiki, Reiko Uchiki, Anna Kazumi Stahl in front of a typical home in the Gentilly area of New Orleans.

The future of the Nikkei of Louisiana:

As assimilation increases with each generation, perhaps the need for an ethnic community wanes. The New Orleans Sansei generation were few in number to begin with and, as children, they attended social gatherings often by obligation to their parents. Most attended different schools and made their own set of mostly Caucasian friends. Consequently, many stopped attending the different social functions sponsored by the Japan Club and Japan-American Society.

Many left Louisiana to attend out of state colleges, or found work elsewhere. The now shuttered Oriental Merchandise was last run by Stanley Tamai. A Sansei, Stanley met and married his wife Linda, a half Japanese and half Filipino Texan, while living in San Francisco, but he returned to New Orleans when his father, Frank Tamai, fell ill. Stanley's two Yonsei children grew up in New Orleans fully assimilated into American society.

Other Sansei who remain in New Orleans have chosen to lead lives separate from the social network that once filed a critical need for the Isseis and Niseis. The Japan-American Society and Japan Club of New Orleans are comprised mostly of Japanese who were born and educated in Japan, as well as non-Japanese with trade and cultural interests in Japan. These organizations have few Japanese American members. The annual New Year's party at the Consul General's continued before Katrina but had morphed into more of a cocktail party than the family friendly affair of the past.

Mrs. Arimura remains active in the community contributing her talents in the areas of tea ceremony and other traditional Japanese arts. The Japan Club is still active with Bonenkai being the highpoint; however, the Club thrives because the current members, like the original Issei, find comfort in being around others who speak Japanese and understand Japanese culture.

The recent earthquake and tsunami that devastated Japan’s northeastern regions also brought the New Orleans community together, sparking fundraising efforts and a chance for Nikkei in Louisiana to remember their roots and again aide their countrymen in a time of distress and need. Yet, as the grandchildren of the original Issei move on, a new but smaller crop of Issei move in, continuing the next phase of the Cajun Nikkei community.

Notes:

Personal thanks to Mr. Touru Yenari, Ms. Dolly Okubu, Mr. Stanley Tamai, Dr. Akira Arimura, Mrs. Katsuko Arimura, Mr. Mark Arimura, Dr. Larry Yastu, and Mrs. Setsuko Asano for providing much of the above information over the course of many years through informal interviews. Personal thanks to the authors’ own families for sharing family history and culture, never letting us forget who we are. Thanks to Pepper S. Caruso for editing.

* To learn more about Japanese American in Louisiana, check out the article by Greg Robinson, "THE GREAT UNKNOWN AND THE UNKNOWN GREAT: The astonishing history of Japanese Americans in Louisiana (part 1 & part 2), originally published on Nichi Bei Weekly on November 3 & 11, 2011.

© 2012 Midori Yenari & Anna Stahl