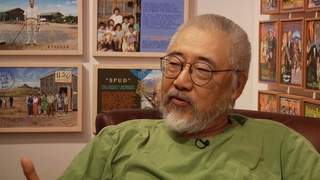

Interviews

Trying to get back into camp

Well, my worst day occurred when I actually had left camp, and I tried to come back in. I left camp in June of ’44. When I left camp I felt I had to get out, and so did most of my friends. Most of my friends left a day after graduation, and I left a week later. Most of them left alone, or if they were with their friends, they were out with their friends on the bus ride or the train ride. But once they got to their destination, they would be alone, or they might be with one friend but nobody knew anybody. (laughs) But we still had to leave to get out of the place, because camp was just destroying us psychologically—our morale.

But anyway, in ’45, I tried to get back into camp because I wanted to talk to my parents. My father wanted to come out to Madison, Wisconsin, where I was living. I was trying to help my sister and brother by working and giving them part of my wages. And I said, “You’d just be another mouth to feed. You got to go someplace where you can support yourself, because you can’t get a job in Madison, Wisconsin. They didn’t hire Issei.” So I thought, well, I’d better go to camp and talk to him about it. And this is March of ’45, and they wouldn’t let me in. They said, “Well, why do you want to come?” First of all, they said, “Where is your permit?” I said, “What permit?” You have got to remember; first of all, there was no exclusion order. That had been lifted in January ’45. So theoretically, we could move anywhere we wanted to move, including California [and] travel around. And then they said [again], where is my permit? And I said, “What do you mean, a permit?” Again they said, “Well, you got to get a permit.” I said, “Where? I live in Madison, Wisconsin. Where am I supposed to get a permit? I don’t know anything about a permit.” So they said, “Well, why do you want to come here and see him?” I said, “Well, I want to talk them out of moving to Madison, Wisconsin,” and I explained why. And they said, “Well, you can’t do that.” I said, “Why not?” [They said], “Our policy is to get people out of camp.” So you know . . . it was just so frustrating talking to these people, so I said the equivalent of, oh, the hell with it. Kick me out or don’t let me in, or whatever—something like that. Typical dumb thing to say, but I was a dumb kid.

So they stuck me in jail. I waited in jail, and then they posted a guard, a soldier with a rifle, [and] put me on the next bus out. I told the soldier, I said there’s another bus that leaves a couple of hours later that still can get me out. Oh, the other [thing] they did, which is just unbelievable, is they issued an individual exclusion order for me. You see, they could do that, to keep me out of the state of California. So I had to be out of the state of California by midnight of that day. And it’s crazy. I mean, why do you they do that? (laughs) Kick me out of the state of California by midnight! But anyway, I said, well, there’s another bus that comes a couple hours later, and all my friends are down here by the gate. I’d like to talk to them. My father was there, [so I said] I’d like to talk to him. And the soldier says, “Well, my orders are to put you on the next bus.” So what am I to do? I can’t argue with him. He’s got a gun.

So I got on the bus. I think that was the last time in my life I really cried. I cried since then, you know, but not that much. I was really overwrought. But it was a real bad experience. And the thing about (laughs) experiences like that, is if you’re running a government, don’t do that to people because those kinds of people come back to haunt you. And I think that’s what happened as far as the Redress Movement goes.

Date: June 12, 1998

Location: California, US

Interviewer: Darcie Iki, Mitchell Maki

Contributed by: Watase Media Arts Center, Japanese American National Museum

Explore More Videos

Necessary apologies (Spanish)

(b. 1962) Peruvian Poet, Okinawan descendant

Angry about the mistranslations of his father’s testimonies

(1919-2020) Member of the 1800th Engineering Battalion. Promoted Japan-U.S. trade while working for Honda's export division.

Not able to go to Manzanar on a furlough

(1919-2020) Member of the 1800th Engineering Battalion. Promoted Japan-U.S. trade while working for Honda's export division.

“All I have dear to me is in the camp”

(1919-2020) Member of the 1800th Engineering Battalion. Promoted Japan-U.S. trade while working for Honda's export division.

Feelings upon listening to the imperial rescript (Japanese)

(1928 - 2008) Drafted into both the Japanese Imperial Army and the U.S. Army.

Yoshitaro Amano, Forced to Return to Japan by Prisoner of War Exchange Ship (Japanese)

(b. 1929) President of Amano Museum

Getting measles at the camp

(b. 1938) Japanese American painter & printmaker

Differences between Parents

(b. 1938) Japanese American painter & printmaker

His mother’s experience of the camp

(b. 1938) Japanese American painter & printmaker

Returning to Japan on a prisoner-of-war exchange boat (Japanese)

(b. 1948) Executive Director of Amano Museum

Camouflage Net Weaving in Manzanar

Japanese American animator for Walt Disney and Hanna Barbera (1925-2007)

Developing Art Skills in Camp

Japanese American animator for Walt Disney and Hanna Barbera (1925-2007)