While working on the forthcoming Cruising J-Town exhibition, I came upon the photo of a WWI veteran in his naval uniform, arriving at the Santa Anita Assembly Center in April 1942. It’s a profound, powerful image; an American veteran being incarcerated by his government for no other reason than being of Japanese descent. The photo has been republished numerous times, including in JANM’s permanent display, Common Ground. However, for all its uses, I noticed the veteran was never identified by name. Here he was, serving as a profound symbol for an injustice done to his entire community, yet our Mystery Veteran (MV) was rendered anonymous. It felt like time to change that.

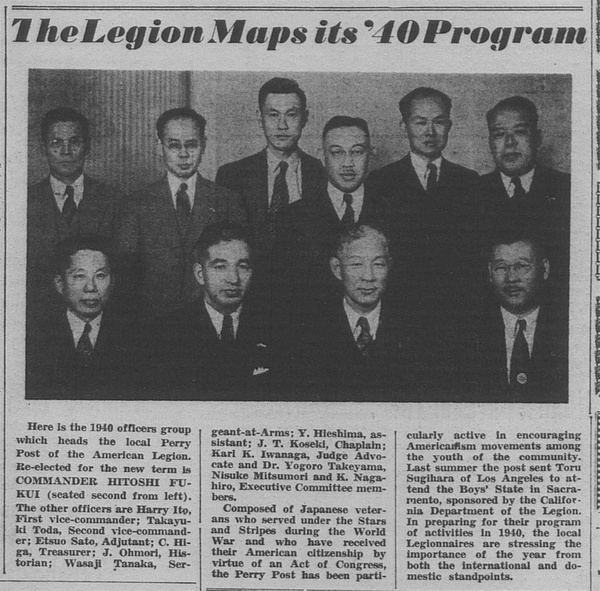

Trying to identify someone from an 80+ year old photograph would always have been a challenge. If MV had appeared at Santa Anita wearing civilian clothes, our endeavor may have been impossible. But his uniform gave us important clues, as did the original 1942 photo notes. First, I found that the image, by sheer coincidence, had been posted on the social media site, Reddit, just weeks earlier. Readers familiar with military emblems explained that MV had likely served in the U.S. Navy as a ship’s cook or mess attendant, with at least 20 years of service. Someone noted that MV was wearing an American Legion cap and when I zoomed onto that detail, I saw that the cap had a “525” on it. A quick search led me to the Commodore Perry Post 525, organized in Los Angeles in 1935 to honor American veterans of Japanese descent, likely the first American Legion post to do so.

Next, the photo, originally shot by Clem Albers, was dated April 5, 1942, with a handwritten note reading “Santa Anita—Arrival From San Pedro.” I thought this meant that MV was from San Pedro but later realized it signified he had driven from San Pedro as part of an early April round-up of Nikkei in South Bay cities like Redondo Beach, Wilmington, Lomita, Torrance, etc. While most had been sent to Santa Anita by bus or truck, military officials organized a large convoy on April 5, 1942: Easter Sunday. Nikkei who still owned their own vehicles were told to convene along 7th Street in downtown San Pedro before being escorted to Arcadia. San Francisco Chronicle reporter Milton Silverman covered the event, describing the caravan’s formation:

By 1 o’clock there were 74 cars there—new sedans, old jalopies, trucks loaded with blankets, suitcases, kitchen utensils, lawnmowers, and children. There were 328 people in that caravan, involving 68 families. Local police had kept three blocks of West 7th closed to automobile traffic, but they couldn’t keep pedestrians away. They didn’t seem to be ordinary flocks of curious strangers. They were friends of the evacuees, and when the caravan started off, these friends stood on the sidewalks, waving goodbye and good luck. There were few tears involved in the departure, and all of these were contributed by the [white] Americans who stayed behind. “Gee,” one woman said, “we were sure anxious to get ’em out of here, but we’re going to miss them a lot. I wonder if we weren’t making a lot of fuss about nothing.”

This told us that MV likely lived somewhere in the South Bay, including but not limited to San Pedro. This felt like enough information to begin our search.

I first worked with historians at Densho, Brian Niiya and Geoff Froh. Searching through the National Archives and Records Administration databases, they came up with a viable candidate right away: Taro Sahara of Carson. He had been a ship’s cook with over 20 years of experience, was a member of the Perry Post 525, and had been sent to Santa Anita. The evidence looked strong enough that I even tried contacting Sahara’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren through social media to see if they could verify the photo as being Sahara.

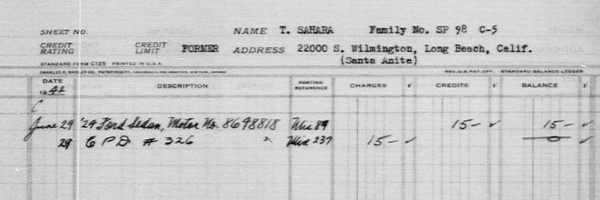

However, while awaiting word from them, I came upon evidence that cast Sahara’s candidacy in doubt. The reason I first came upon MV’s photo is because I was interested in Nikkei incarcerees who had driven themselves to places like Santa Anita and Manzanar. This was something that hundreds of families did in the early weeks of the “evacuation” because it allowed them to circumvent the infamous “bring only what you can carry” rule by packing their family cars with more belongings. However, upon arriving at these assembly and incarceration centers, officials immediately impounded people’s cars and forced their sale to the government. Geoff Froh at Densho sent me digitized records of those sales and within them, I found the actual sales receipt for Sahara’s car: a 1924 Ford, better known to most as a Model T.

The problem is that the car in the MV photo wasn’t a Model T. While we still haven’t positively identified it, based on its design, MV’s car was a ~1940 sedan, possibly either an Oldsmobile or Nash. There was no other receipt indicating that Sahara came to Santa Anita in a different car. Meanwhile, his descendants couldn’t confirm if the photo was of him or not; Sahara died in 1949, long before any of his grandchildren had a chance to meet him. We had to start over.

I began researching more about the Perry Post 525 in the archives of the Rafu Shimpo, hoping to find a list of names or photos I could use to match with MV. While a few leads arose, all had something disqualifying: people were in the Army, not the Navy, or their prewar address was near J-Town, far from the South Bay. I finally asked JANM’s social media team to put the photo out on the Museum’s accounts and see if crowd-sourcing could help; the post appeared on July 18, 2024. Of the many people who saw the posts, one of them was Jamie Henricks, JANM’s archivist. Later that day, she sent me an email, asking: “what about Hikotaro Yamada?”

Jamie had found a list of veterans who were part of Jerome’s American Legion post. Within there, she found Hikotaro Yamada, who lived in Torrance, had been a ship’s cook, was a member of the Perry Post 525, and was a Santa Anita incarceree. (Notably, he and Taro Sahara shared similar military backgrounds, started the Legion post at Jerome together, and even lived near one another before the war).

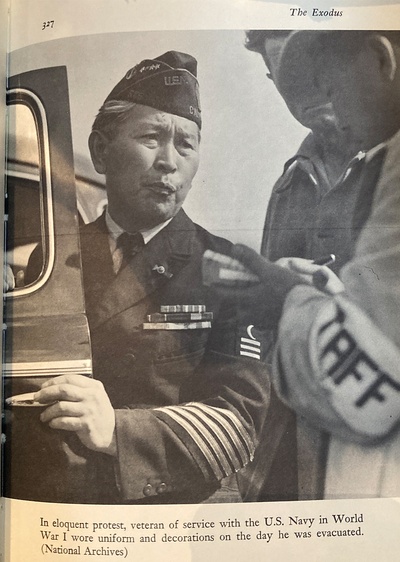

The clincher was what Jamie found next in a July 1970 issue of the Pacific Citizen (see page 4) about how the San Diego JACL was hosting an event celebrating Issei veterans, with Yamada being honored as the oldest living Nikkei veteran. In that story was an incredible and unusual detail: “Mr. Yamada is shown on page 327 of the [Bill] Hosokawa book Nisei: The Quiet Americans.” Jamie ran to the library inside of JANM’s Hirasaki National Resource Center and pulled out a copy of Hosokawa’s pioneering 1969 book. Turning to page 327, she found this:

(Ironically, Hosokawa’s book didn’t name Yamada either, despite putting the same photo onto the cover of its 2002 revised edition.)

I sat, stunned with amazement. My wife, Sharon Mizota, who had followed the saga since day one, was moved to tears. We had confirmation: our Mystery Veteran was Hikotaro Henry Yamada.

As a bonus, using this new information, I found a photo of that San Diego JACL event, which included Hikotaro and his wife, Mai Ito. Hikotaro was almost 30 years older than his 1942 photo, but the resemblance was still there.

Finally, after 82 years, we could now give Yamada a proper name credit in his iconic photo. Densho has already updated their records, while UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library is in the process of updating theirs. Hopefully, for all future uses of this image, Yamada’s name will be mentioned.

Meanwhile, thanks to knowing his name and all the reporting in that Pacific Citizen article, we can also share more of Yamada’s personal story:

He was born Oct. 8, 1883, in Hakodate, a coastal city of Hokkaido, Japan. In his late teens, he joined a whaling vessel that took him to New England in 1903, entering the U.S. via New Bedford, MA. The next year, he enlisted in the Navy at Newport News, VA.

His first post was a ship’s cook on the USS Columbia and in total, he served on 20 different ships over the next 20 years. Over the course of his military career, he was a witness to the naval bombardment and marine invasion of Veracruz, Mexico in 1914 and accompanied the fleet during WWI to Vladisvostok in 1917. The next year, he was naturalized as an American citizen, the first person of Japanese descent in the Navy to be granted citizenship. This was a rare privilege accorded Issei who served in the military since, at the time, racist legislation specifically forbade most Asian immigrants from ever attaining U.S. citizenship.

Yamada retired from the Navy in 1924 as a chief petty officer and according to the Pacific Citizen, was a “darn good cook.” He then worked with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey from 1924–26 and was likely in the navy reserves until he “finally mustered out” of the military in October 1934. According to Census records in 1940, he worked as a cook, living with his wife Mara Yamada in Torrance.

As we know, he came to Santa Anita on April 5, 1942. He and his wife, whose name in camp records was listed as Kito Yamada, were transferred to Jerome, and later Gila River. In the summer of 1944, Kito passed away from complications after a stroke; she was 62.

Yamada was released from Gila River in 1945, and in January 1950 married Mai Ito Watanabe in San Diego. Later that year, the two were living in Hikotaro’s original, prewar Torrance home, now farming strawberries. The same year, he marched in a large American Legion parade in downtown Los Angeles, in front of half a million spectators.

It’s an eerie coincidence that Hikotaro died at the age of 91 on April 5, 1975, 33 years to the day that he reported to Santa Anita. Mai Ito passed away four years later at the age of 80. Both were laid to rest in Cypress View Cemetery in San Diego. Best as we know, they had no next of kin.

* * * * *

Special thanks to UC Riverside’s Gena Carpio, the Antique Auto Club of America’s Matt Hocker and Warren Erb, Densho’s Brian Niiya and Geoff Froh, Ron Inatomi, JANM’s Alexa Nishimoto, Anna Iwata, and especially Jamie Henricks. This post is dedicated to Hikotaro Yamada, Taro Sahara, and all the Nikkei veterans unjustly incarcerated during WWII.

Cruising J-Town opens July 31, 2025 at the Peter Mullin Gallery at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena.

© 2024 Oliver Wang