Ken Nakazawa would have defined himself as an internationalist. Throughout his career, he advocated international understanding through study of foreign cultures. At an Institute of International Relations in Riverside in November 1927, he gave a speech proposing that differences between East and West be composed through “positive differences,” as had been the case in art and literature.

Yet in the years before 1931, he hardly touched on international politics in his public statements and writings. A rare exception came in June 1928, when three Issei in Los Angeles were arrested on suspicion of being communists. Nakazawa made a statement on behalf of the Japanese Consulate refusing to support them. Japan’s government, he proclaimed, “is unalterably opposed to communism,” adding, “We do not countenance it in Japan and we will not countenance it among our citizens in America.”

Yet, because of his literary reputation, in the wake of Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in fall 1931, he either volunteered or was pressed into service to present the Japanese side of the question. In November 1931, he spoke on Manchuria over radio station KNX. On December 11, 1931, he participated in a debate on the issue with Dr Wing Mah, professor of political science at University of California, at an Institute of International Relations meeting in Riverside, California.

As the Christian Science Monitor reported, Nakazawa insisted that Japan did not covet one inch of ground in Manchuria, presenting as proof repeated statements by Japanese officials. “As soon as the safety of life and property is fully guaranteed,” he concluded, “[Japan] will gladly withdraw her army.”

Despite Nakazawa’s confident (or deceitful) assurances, the Japanese Army remained in Manchuria and created the puppet “Northeast Supreme Administrative Council,” which proclaimed the state of “Manchukuo” in February 1932. During February-March 1932 (amid his preparations for that summer’s Olympic Games), he leaped again into action. Nakazawa made a dozen speeches on the Manchuria question across the region, including Laguna Beach; San Luis Obispo; Guadalupe; Lancaster; Terminal Island; El Monte; Santa Maria; Anaheim; and Dominguez Hills. He contributed an article, “The Sino-Japanese Controversy,” to the new USC journal, World Affairs Interpreter.

While the question of Manchuria soon fell from prominence in public debate, the larger question of Tokyo’s policy and potential conflict with the United States mobilized Nakazawa to intervene anew. In December 1932, he participated in an Institute of World Affairs with famed writer Inazo Nitobe. The following year, he spoke on “The Pacific and the World at Peace.”

In April 1934, the Japanese Foreign Office public declared its “Pan-Asiatic doctrine,” an “Asian Monroe Doctrine” which asserted Japan’s primary role in protecting peace and order in East Asia. In the wake of the announcement, Nakazawa addressed a Presbyterian Ministers’ Association at the Y. M. C. A. building in Los Angeles.

According to the Los Angeles Times, Nakazawa insisted that Japan favored the established “open door” in China, and stressed that the Japanese people and their government had only the friendliest feelings toward the United States. He charged that propagandists were trying to stir up needless trouble between Japan and the United States in the Pacific: “An attack by Japan upon America, Nakazawa stated, “would be like a mouse attacking an elephant.”

Soon after, in early 1935, he took part in a debate at the Friday Morning Club on relations between China and Japan. In response to Dr. No-Young Park of Harvard, who complained of Japan’s treaty violations, Nakazawa denied that Japan had violated any treaties, and blamed communism for tensions between China and Japan.

Similarly, in April 1935, he delivered an address to the Women’s University Club, “Present-Day External and Internal Problems of Japan.” He scored misguided patriots who tried to show their devotion to America by manifesting hatred of other nations as a menace to world peace. His campaign showed signs of success. In November 1936, when Nakazawa addressed the Hollywood Knights of Pythias, the Los Angeles Times referred to him as a “Japanese peace leader.”

In summer 1937, Ken Nakazawa traveled to Japan—despite his status as a specialist on Japanese culture, he had not visited his native country in 30 years. He did not bring his family. On the boat to Yokohama, he met with student delegates from the Southern California Christian Young People’s kengaI kudan, and addressed them on phases of Japanese life. He may have been present at the July 4th celebration held by the students on board.

In his application for reentry to the USA, Nakazawa later claimed that his trip’s purpose was to attend an educational conference sponsored by the Japanese ministry of Foreign Commerce. A newspaper report states that he was indeed present at the Seventh World Education Conference in Tokyo on July 26. He arrived back in North America by September 3.

That said, the nature of his activities during his Asian trip remains murky. It was during early July 1937 that a skirmish at the Marco Polo Bridge led to a full-scale invasion of China by Japanese troops. According to the Japan Times, when Nakazawa spoke in Tokyo on August 9 under the auspices of Kokussai Kyokai, he claimed that he had just spent a month in North China. Given his arrival dates and documented time in Tokyo, this seems highly unlikely.

Then, following his return to Los Angeles, he launched a propaganda offensive in support of the Japanese invasion. On September 23, Frank Chuman (then a college student) wrote in Kashu Mainichi that Nakazawa had been invited to address the local chapter of the Japanese Student Christian Association, and told its members to study the official line in order to reproduce it:

Japan’s reasons for the present Sino-Japanese situation should be understood by every nisei college student. I would also like to suggest the answers which may be given should American people ask you about the present situation, so please have many questions ready.

Two weeks later, on October 10, Nakazawa published a front-page article in Los Angeles Times, “Japanese Professor Tells Causes of Imbroglio.” Responding to an article by Chinese consul T.K. Chang denouncing Japan’s invasion, Nakazawa defended Tokyo’s actions, insisting that Chinese forces at the Marco Polo bridge had provoked a response by Japanese forces and that Japan was blameless in the conflict.

Five days later, he delivered a radio address, “The Truth About China,” over KRKD radio. According to an account in Kashu Mainichi, Nakazawa asserted in a machine-gun-like delivery that he had just returned from a fact-finding mission to Manchukuo and North China. Not only were the Chinese an unsanitary and irresponsible race—“China is the dump yard of the world,” Nakazawa proclaimed—but savage.“Mass murder of civilians is a common thing to these people who were ruled by blood-thirsty warlords and bandits. The mass murder of Japanese and Korean civilians in Tung Chow is just another day’s work to these ruthless outlaws….Japan was the only sufferer of China’s cunning and sugared policy of spasmodic anti-foreignism,” the speaker declared. Nakazawa presented the Japanese invasion in a noble light. “The sacrifice paid by Japan to restore peace and order in China is so great that it is ridiculous to criticise Japan as having territorial ambition.”

Over the following weeks, Nakazawa continued his public defense of Japan. Unlike in 1931, when he engaged in debates wth Chinese, here he spoke primarily to Japanese American audiences—it is not clear whether the Chinese refused to deal with him or he simply preferred friendly audiences.

In October, he spoke at an open forum on the Sino-Japanese situation sponsored by the Orange County JACL, and in November at a Buddhist temple in San Diego, where he first delivered his speech in English, then in Japanese for the benefit of older people.

At a civic conference in Upland, California in November 1937, he contended that Japan should be congratulated for fighting communism in China: “Communism is engulfing China and unless it is stopped all of the western civilization will be included.” Similarly, in a December 3 radio address over station KFWB, “America’s Neutrality Threatened,” Nakazawa referred to the unjustifiable condemnation of Japan by foreign countries and the threat of economic loss to American trade with Japan and Asia if Washington should institute boycott measures against Nippon.

That same month, at a World Affairs Institute at the Beverly Hills Hotel, Nakazawa discussed “Japan’s Stake in China,” declaring that Japan’s present military mission in that country would not be completed until the Communists ceased their activities.

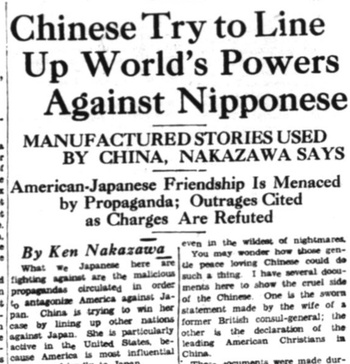

On December 6, 1937, just days before the onset of the Nanjing Massacre, Nakazawa contributed an article to the Nichi Bei, titled “Chinese Try to Line Up World’s Powers Against Nipponese.” In it, Nakazawa claimed that Chinese were trying to turn world opinion against Japan through false propaganda stories of Japanese atrocities. In fact, he contended, the Japanese military “was doing all in her power to avoid needless injury or death. Sometimes she went even so far as to risk the danger of ambush by announcing her intention of attacking certain sections several days in advance. She always gave every assistance to those who wished to escape the scene of danger.”

So far from acknowledging the costs to China of the Japanese invasion, Nakazawa underlined Chinese atrocities, notably the mutiny at Tungzhou (in the then-Japanese puppet state of East Hebei) in which 300 Japanese men, women and children were killed. Nakazawa claimed—with doubtful accuracy—to have been an eyewitness.

I was in Tungchow after the massacre. The scene which I saw there was horrible beyond my power of description. I saw the body of a two year old girl with the skull and limbs torn off. and the trunk trampled down flat as a pancake. Every inch of the ground was blood-soaked…

In the new year 1938, he renewed his focus on the war in China. In January, he delivered a speech, “The Outcome of the Sino-Japanese Conflict” at the Higashi Hongwanji Y.B.A. meeting. Soon after, Nakazawa spoke to students at San Diego State College. His “Japanese Point of View” on the Sino-Japanese conflict was enthusiastically received. In February 1938, he addressed the Orange County Rotary Club on the war:

China has planned to win her cause by winning the support of the United States. Not only must the United States consider the loss of trade with Japan— three times as much as that of the trade of this country with China-but the nation also must consider the great sacrifice which would be entailed should it take the part of China in the present conflict..A serious argument advanced by China is that Japan is the aggressor and this argument is brought about because Japan is fighting the war in China.”

Nakazawa closed by stating that China looked outward for the causes of unrest and trouble, rather than looking inward and seeing her own responsibility.

In April 1938, an article by Nakazawa appeared in Volume 1 of the “Pacific Review,” a Japanese government-sponsored brochure on the Japanese people and the nation’s foreign relations. In the following months he spoke on the Sino-Japanese conflict to audiences in San Diego, Chula Vista, Anaheim; Santa Ana (where he referred to the Sino-Japanese conflict as a “family quarrel” in which there could be no divorce, and that must be settled by those interested); San Bernardino; and Garden Grove.

While he kept to a set of common themes, and never abandoned his unwavering support for Japan’s aggressive policy, he reshaped his discourse over time. For example, in a speech before the Oxnard Rotary Club in Spring 1941, Nakazawa repeated his longtime contention that the basic friendship between Japan and America was being strained by the efforts of war mongers. This time, however, his address centered not the occupation of China, but Japan’s interest in the Dutch East Indies, which Nakazawa insisted stemmed not from desire for conquest but trade. It is impossible to know at this point how much Nakazawa was aware of the Nanjing massacre or the horrors of the Japanese occupation of China. What is clear is that, as the United States and Japan moved toward war, his outspoken defense of Tokyo's official line made him suspect in the eyes of American authorities.

To be continued ... >>

© 2024 Greg Robinson